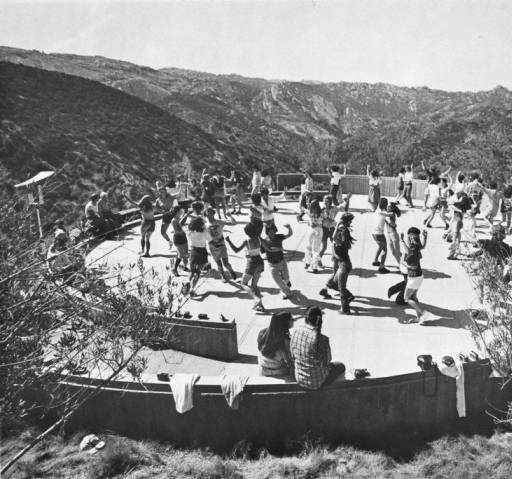

Pioneering Jewish educator Shlomo Bardin is typically credited with the first uses of tikkun olam in its contemporary American context. Having founded the Brandeis Camp Institute in 1943, first in the Pocono Mountains before finally settling in Simi Valley, California, Bardin crafted an ideology of Jewish engagement and education that brought together the American recreational summer camp, the “cooperative self-help” ethos of the Zionist kibbutz model, and the informal, heritage pedagogy of the Danish Folk High School he had once observed en route to Palestine.1 What eventually became the Brandeis-Bardin Institute was largely a laboratory for the development of American-Jewish leaders, following United States Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis’ intertwining of Zionist nationalism with American patriotism.

These threads—entangled at the Institute in southern California—illuminate some of the complex origins of tikkun olam in its widespread use by various Jewish denominations and non-profits today. Bardin introduced the concept as early as 1950, drawing on the phrase “l’takein olam b’malchut shakai” (“to repair the world in the kingdom of G-d”) in the second paragraph of the Aleinu prayer. The immediate textual context of the phrase refers most directly to the eradication of idolatry, which itself contains a multitude of meanings. But Bardin intended to express a more general belief that it “was the obligation of Jews to initiate and fully participate in the mending of our broken world.”2 This dual focus on a particularly Jewish obligation and a more universal vision reflects the layered influences of Bardin’s personal journey: from Russian socialism, to Labor Zionism, to volkish pedagogy, and finally to the American summer camp.

It is possible that Bardin was familiar with Ahad Ha’am’s derision of “tikkun ha’olam” in his 1903 Shiloach essay, “Tikkun Ha’olam and Zionism”: “Our youths are so used to dwelling on and dealing with the questions of ‘Tikkun Ha’olam,’ until [for] too many of them this question became their spiritual focus, and unknowingly the center of all questions that engage them, including the question of Zionism.”3 Ha’am rejected such lofty and ultimately shallow approaches, indicating his rejection of the creation of a Jewish national home in Palestine as a panacea for Europe’s Jewish problem. This rejection is notable because Ha’am’s cultural nationalism seems to align with Bardin’s own project, making Bardin’s use of tikkun olam an interesting reversal. Like Ha’am, Bardin’s Institute cultivated a kind of Jewish cultural nationalism; but like other political Zionists, Bardin was invested in organizing and isolating a community on (native) land. One colleague described Bardin as a “small-z Zionist.”4

What, then, does the concept imply about efforts at Jewish engagement, community-building, and social justice work today? Is there a kind of “small-z Zionism” that runs through tikkun olam today, pulled as it is between revitalizing Jewish community/identity and more worldly vocations? Does its grandeur distract from crafting specific solutions for specific problems? And does its history reveal the complex layers of migration, settlement, and community construction that haunt contemporary Jewish communities? Bardin’s experimental laboratory signals how the idea of tikkun olam that we now consider ubiquitous has particular roots in multiple ideological threads that converged on the Western frontier of the United States, where it was also invested in the quasi-Zionist construction of a new Jewish subject.

The following pieces—including essays from Gabi Kirk and Benjamin Kersten, a source sheet from R’ David Seidenberg, and succinct reflections from Jewish organizations today—explore these questions, interrogating the limits of tikkun olam, and stretching its contemporary meanings backward by putting them in conversation with the rich rabbinic tradition.

- Shlomo Bardin quoted in Jenna Leventhal, The Brandeis-Bardin Institute (Los Angeles: American Jewish University, 212), 11

- Ibid., 40

- HaShiloach, vol. 11, booklet 4, translation by Shlomi Ravid

- Qtd. in Leventhal, 14