I

In late winter 1994, Kerry James Marshall drove down the familiar streets of Chicago’s South Side while on his way to the bank. For the first time, he noticed a six-pointed star spray-painted on a dumpster. It reminded him of another six-pointed star he saw earlier that morning: a yellow piece of felt with Jude written in the center, the kind the Nazi regime forced onto Jews in Europe. The face of the man who had willingly pinned the star to his chest had an otherworldly grin, the beard of a Mesopotamian judge, and a knit kippah. Marshall had been looking at the photograph of a mass murderer: Baruch Goldstein. Earlier that week, Goldstein opened fire in the Ibrahimi Mosque in Hebron, slaughtering 29 Muslim worshippers. The artist began to photograph the spray-painted stars tagged around Chicago, the stars he had first noticed because of their similarity to the shape of the one Goldstein wore on his chest. Now, Marshall saw them everywhere.

II

In the wake of the 1991 Crown Heights riots, community groups went to work to rectify the atmosphere of hostility and bitterness. Basketball games were organized. Leaders such as Jesse Jackson and the Lubavitcher Rebbe spoke out. Cultural institutions collaborated. The NAACP and the Jewish Museum of New York were among the organizations galvanized by the riots. The two institutions crafted programs for school children from majority Black public schools in Crown Heights and students at their neighboring Jewish day schools. In addition, another collaboration was on its way.

Bridges and Boundaries: African Americans and American Jews was the name of both a collection of essays and a museum exhibition, a collaboration between the NAACP and the Jewish Museum, that both debuted in 1992. The exhibit brought together more than 300 artifacts and toured seven cities, endeavoring to show the points of tension and solidarity between the groups. Here, the “Black-Jewish relationship” was narrated as a once-harmonious encounter between two discrete communities that had been recently disrupted by bitter misunderstanding. Both the essay collection and the exhibition are a resource for understanding the various ways institutions have construed and constructed a conversation about Jewish and Black identities and groups. And I have hardly exhausted it in my research here.

When the exhibition travelled to Chicago in 1994, the city’s Spertus Museum of Judaica took charge of curating a complementary art show composed of 12 local Black and Jewish artists. Interestingly, the director of Chicago’s Dusable Museum of African American History declined to collaborate with Spertus. Interviews with the artists, museum directors, and patrons, including many groups of school children, are captured on film. Congruent with the intense, self-conscious documentation of its parent exhibit, Chicago Crossings: Bridges and Boundaries was documented in more than 100 hours of footage shot by nonprofit filmmakers, Kartemquin.

III

Marshall is in his studio. He is talking to a filmmaker. Johnny, one of Marshall’s portraits from the “Lost Boys” series, stares sphinxlike behind him, the Boy perpetually unfinished and his ear not yet pierced with the golden star. The dripping paint of the white star behind him—the star of David, the gang sign, a halo, and a war banner—has yet to drip and descend down his forehead, where it will stop just before his eyebrow.

I pause the video, open a document, and transcribe the text that Marshall has placed next to book covers and mounted on the wall.

IV

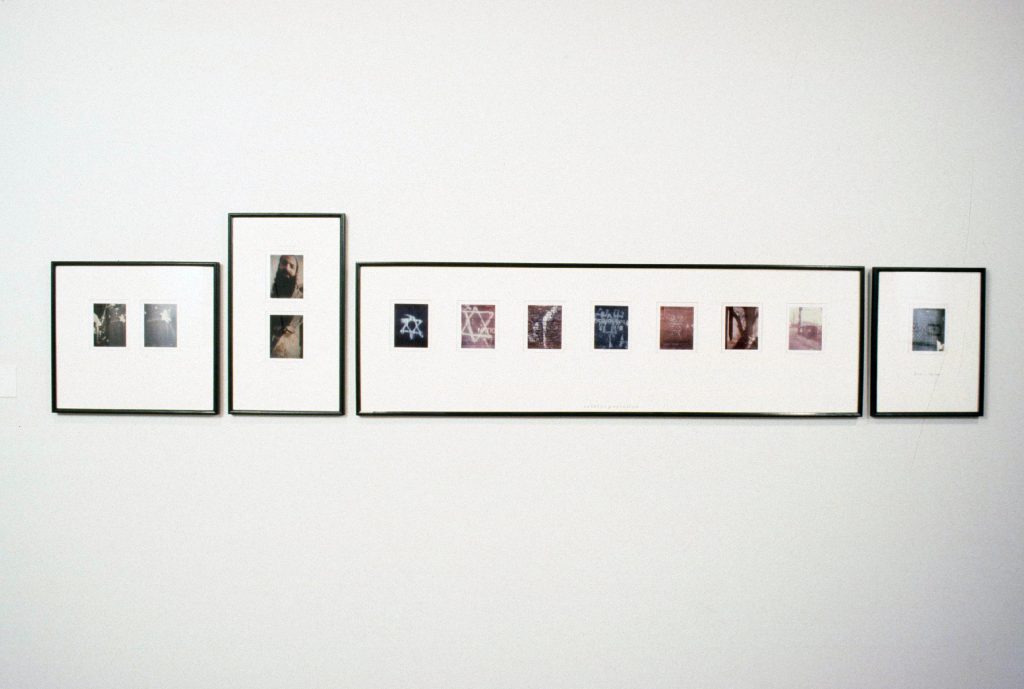

Black and Latino school children crowd around “Shooting Stars.” The series of photographs begins with a yellow star badge forced on a Jewish girl by the Nazi regime. Baruch Goldstein, Jewish terrorist and mass murderer, follows her. On his chest is the yellow star he pinned by choice, a move both intriguing and troubling to contemplate. Then, there is a sequence of six-pointed stars; and the dumpster, the brick wall, and the faded word “Nation” half out of frame. Finally, there is a marshal’s badge, its six silver points held in the hands of the artist—Marshall, who, while arranging representations of violence and power, shares the name of a ranked profession in law enforcement.

“Gang signs!” the students shout. “Those are Folks,” they explain, referring to the umbrella gang alliance Folk Nation organized by the Gangster Disciples’ founder Larry Hoover. The docent at the exhibit asks if they know what the signs mean.

“Each point of the star stands for something,” one says.

“Do you see these symbols in your neighborhood?” the docent asks. Many of them nod yes.

V

Back in Marshall’s studio, he’s recalling what he had heard on the radio. Jewish kids, settlers in Hebron’s Jewish colony of Kiryat Arba, some as young as six or seven years old, are extolling Goldstein as a hero, “as if what he had done had been the greatest thing a Jewish person could do,” Marshall explained.

Marshall meditates on revenge and the valorization of violence, and turns to the “Lost Boys” series—portraits of young Black men killed by gang violence. Some of them become heroes to the younger kids in their neighborhood, Marshall reflects.

VI

Black high school students stand before “Shooting Stars.” One of them deciphers the meaning of the six points: Life, Love, Loyalty, Knowledge, Wisdom, Understanding. An older white man leans on the wall next to the photo series. He stares at the students.

“You know where this stuff starts?” The white man’s question sounds like more of an angry outburst, dripping with paternalistic condescension.

“The home,” one of the students responds, automatically.

“Who’s in charge of the home?”

“Family.” He knows what’s coming.

“Who’s in charge of the family?”

The student casts a knowing, exhausted look away from the man, with whom he never makes eye contact.

“Mother and father,” the student says.

“When it’s your turn…” the man carries on. The specifics don’t matter. The filmmakers witness the exchange. Later, they include the footage in a short follow-up video.

I wonder whether the older white man is Jewish. What difference would that make?

VII

Kerry James Marshall, born in Alabama and raised in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, has been a resident of Chicago for most of his life. By the time of Chicago Crossings, he was in his late 30s and an established artist on the cusp of major success. It was only a few years earlier that he received a MacArthur Genius grant. In 1998, he would have his first solo show at the Renaissance Society of the University of Chicago. While his “Lost Boys” series has been widely shared, “Other Books” and “Shooting Stars” have been all but forgotten. Marshall’s work navigates both the dehumanized, abstracted Black subject and its inverse, its hyper-realistic figuration. In a 1998 interview with Charles Rowell, Marshall detailed his approach:

“There has been a tradition of negative representation of Black people and the counter-tradition to that has been a certain kind of positive image, a thrust on the part of some black artists to offset the degradation that maybe some of the other negative stereotyped images present. But both, in a lot of ways, ended up being a kind of stereotype that denied a certain kind of complexity in the way the Black image could be represented. So I thought, well, there’s got to be a way to do both, to do two things at once.”

It is this kind of treatment that makes Marshall’s contribution to Chicago Crossings so original and so dangerous.

VIII

I’ve transcribed the text on the wall: “…My uncertainty doesn’t lie in the fact that Simone and I are dissimilar. He is a white professor of psychology. I am a black and native American professor of English. He is a Muslim. I am a Jew. He is married to a Black woman. I am married to a woman who is white and native American.” I run it through a search engine. Found it: “The Postmodern Negro” by Reginald McKnight. McKnight is responding to a book on race by T. Abdou Maliqalim Simone.

Rather than a glib comparison of Black-Jewish difference that rests on a binary of Black non-Jews and white Jews, Marshall includes an exchange between two people whose very place in these histories is systematically silenced. In “Other Books,” a binary between two distinct Black and Jewish communities is replaced by a palimpsest, in which meaning and identities are layered on top of one another, in a confused and fluid relation. The excerpt of this text in “Other Books” is rotated on its side.

IX

The filmmaker implores a white Jewish woman, incensed by the spray-painted stars of David defacing property, to spend a few more moments in front of “Shooting Stars.” Those are gang signs, the filmmaker says. And do you know who that is?

“Is that Goldstein?” she asks. But she already knows.

The work starts to make sense to her.

“You know, he violated us,” she reasons. “Like how the gang violates the Black community.”

So much is unsaid. The brutal pride of the Jewish terrorists and their utter disregard for anything outside their movement is at once empowering and incredibly toxic. How briefly, but somehow truthfully, this phenomenon overlaps with the Black gang.

The coherence of the institutional narrative in which Blacks and Jews are two separate communities that share a past of common struggle and profound tensions begins to unravel.

The coherence of the institutional narrative, established by the NAACP and the Jewish Museum of New York as well as the Spertus, in which Blacks and Jews are two separate communities that share a past of common struggle and profound tensions begins to unravel. In its place are the insights gained from unstable metaphors. A glimpse of familiarity flashes between the Kahanists and the Gangster Disciples, perhaps in their shared territorial violence, or their ethics of retribution and strength. But it’s only a flash, its meaning disappearing as quickly as it arrived. Such an encounter does not lead to a better grasp of simplistic narratives, but rather an unsettled revisiting of the very subject matter itself.

X

“That African Americans and Jewish Americans share some similar historical experiences goes without saying. What I had never really thought much about, though, is how much information about Black history and culture came to me by way of Jewish folklorists and historians.” —Kerry James Marshall’s artist statement in the catalogue for Chicago Crossings: Bridges and Boundaries.

XI

Refuting the logic of an institutionalized “Black-Jewish relationship” by writing a counter-history runs the risk of reaffirming the very terms of the engagement. To see a way out of this maze, we must accept that we are already trapped inside.

Marshall is indifferent to this “relationship,” but also does not deny its existence. This ambiguity allows him to venture into new territory. Rather than asking what befell a once-harmonious relationship, Marshall asks: where do Jewish and African American worlds intersect?

Marshall learned about African and African American cultures through the work of a white Jewish anthropologist. Melville Herskovits’ canonical Myth of the Negro Past (1941) was formative for Marshall, and this circuitous engagement with African and African American cultures through white Jewish interlocutors prefigures Marshall’s recognition of the spray-painted, six-pointed stars after observing an image of Baruch Goldstein.

One can make the opposite observations as well. The militant machismo of white Jewish terrorists borrowed from Black Power activists; in an obvious nod to Malcolm X, the paramilitary Jewish Defense League was formed to protect Jews “by any means necessary.” And Herskovits’s anthropological work on the “acculturation” of African groups in the Americas challenged biological conceptions of race at a time when Jews in Europe were being murdered in mass because of them.

XII

“It was like a drive-by,” Marshall explains of Goldstein’s massacre. Marshal likened Rabbi Meir Kahane’s movement—the Jewish Defense League that evolved into the Kach political party in the state of Israel and of which the terrorist Goldstein was a member—to an African American gang, comparing their violent control of territory, penchant for retribution, and engendering of pride and belonging. Marshall reasoned that Goldstein massacred Muslims at prayer as an act of revenge for the assassination of Kahane, similar to the revenge drive-by shootings perpetrated by street gangs. Some gang members have as much animosity for other gang members as some Jewish settlers have for Arabs, Marshall adds.

The unsettled territory of Marshall’s project nonetheless touches upon a liberatory imagination.

The lens through which Marshall sees both his Black and Jewish subject matter reveals provocative, if also incoherent and offensive, logic. By likening the contempt gangs have for their rivals to the genocidal hatred that Jewish extremists have for Palestinian Arabs, he levels out important differences and mutes power dynamics. At the same time, he gestures toward alternative understandings. His reading likens Jewish settlers and Palestinian Arabs, while acknowledging that it is violence that keeps them apart. For Marshall to make these kinds of equivalences, the facts of state power and whiteness must be suspended. But the unsettled territory of Marshall’s project nonetheless touches upon a liberatory imagination. Like its subject matter and logics, this imagination too is a slippery substance.

XIII

Marshall printed a photograph of Al Jolson, a white Jewish blackface performer, from a book by white Jewish historian Daniel Leab about the representation of Black people in movies, From Sambo to Superspade (1975). Marshall inverted the colors of the photograph and screen-printed it onto a Hebrew edition cover of Herskovits’s Myth of the Negro Past.

“The image became too obvious,” Marshall said. He left it out of the final composition.

Instead, he turned to a white family’s photo album he had found at a secondhand store. Out of thousands of slides, he searched for any sign of a Black person. All he found was a photograph of a blackamoor figurine, which takes a central place in the T-shaped assemblage, “Other Books.”

“It seemed to tell the whole story,” Marshall explained.

The image of Al Jolson in blackface had been cropped out of a picture. In the original, Jolson was surrounded by beaming Black women. That Marshall ultimately replaced this image for the one of the figurine, picked from thousands of a white family’s photographs, illuminates his process. The obviousness of the stereotypical is avoided. Context is re-sequenced. The stories of race, of its ambiguity and strangeness, are communicated.

XIV

Twenty-five years later, Marshall’s studio is still in Englewood, the neighborhood that has become a metonym for Chicago’s gang violence. Chicago itself has long been widely recognizable as a reference for lawlessness and danger, a boogeyman to frighten the white imagination.

The wounds of Baruch Goldstein’s massacre have not healed. Year after year, Kahanists have held inflammatory marches on Purim, the anniversary of the Hebron massacre, through Palestinian neighborhoods. And now, the Israeli prime minister makes overtures to Kahanists in the Knesset.

Rahm Emanuel, the son of a sabra, is finishing his final year as mayor of Chicago. His grandfather changed their name to Emanuel in order to honor Jewish settler Emanuel Auerbach, who died in an altercation with non-Jewish Arabs in Mandate Palestine. His eight-year term has been characterized by bitter conflict. The murder of Laquan McDonald and subsequent cover-up by the Chicago Police Department, and the closing of more than 50 public schools and the organized backlash of the Chicago Teachers Union, made the city a battleground against policing and privatization.

“Knowledge and Wonder,” a mural made by Marshall for the Chicago Public Library in 1995, was briefly caught in the crosshairs of Emanuel’s power. In 2018, the mayor announced he planned to sell the mural. “You could say the City of Big Shoulders has wrung every bit of value they could from the fruits of my labor,” Marshall told ArtNews of the proposed sale. Emanuel later decided against the sale.

Perhaps the meaning of “Shooting Stars” has only deepened with time, as the relations Marshall recognized in 1994 are compressed even closer.

XV

Chicago Crossings was perceived as underwhelming, confusing, and forgettable. Did the artworks in Chicago Crossings “add up to a better understanding of the issue at hand?” Jay Pridmore replied in his review in the Chicago Tribune: “They do in some cases. Most of the pieces, which were created specifically for the exhibit, are as complicated, or as unresolved, as the events that surround the question.”

Piles of black, white, and clear glass shards greeted museumgoers at the entrance. This was Phoenix, an installation by Gerda Meyer Bernstein. Pridmore said, “One could guess at its meaning, but the idea is largely forgettable.” It was this forgettable, vague message of danger, fear, and difference, distilled into Black and white and shot through with the hope of something new rising from the ashes, that made Chicago Crossings (and Bridges and Boundaries before it) so flawed.

Of Bridges and Boundaries, anthropologist David Rosen wrote in Museum Anthropology in 1992, “This exhibit has a specific political purpose: to use the past to reforge the relationship to the present.” How does Marshall’s work fit into this project? Certainly, his work shares some responsibility for the impression that much of the artwork is complicated and unresolved, but is that a weakness in his specific case? Unlike the vague shards of broken glass, Marshall does not indulge in universalism. Instead, the generalized differences between African Americans and Jews are thrown into the world of the particular, with all its instabilities and unexpected associations.

The past cannot be made subservient to the anxieties of the present. Marshall’s work does not explore the common history of Blacks and Jews, which for him “goes without saying.” Out of indifference, he unleashes a sign shared by a black gang, Nazi governance, the United States police, and Jewish terrorists. Nostalgia, for a brief moment, is suspended and the cynical drives of the culture industry confounded. The fractured ‘Black-Jewish relationship’ as framed by institutional politics is not repaired by Marshall’s work in Chicago Crossings but suspended by raw contradictions. Even if it is just for a brief moment, a flood of possibility breaks through.