Persuading the kid it’s not his fault—how would you go about it? First I must get close enough to try. He’s spent the past week holed up in his room, his door closed, his body sprawled on unwashed sheets, the small personal radio I got him last Christmas turned to NPR and cranked up high to fill the silence. This is the scene I see when, four or five times a day, I open the door, which I do only after knocking and receiving no reply. When I enter, he doesn’t rise, doesn’t even open his eyes. Asked a question, he answers with a single syllable. When I leave a meal on the floor and return, I find it half-eaten, which is something. I assume he isn’t sleeping much. Sunken circles have begun to swell beneath his eyes, which are, to the very iris, his mother’s—a resemblance I can hardly bear. Two activities will coax him from his room: going to the bathroom and visiting the aquarium. So, once a day, to the aquarium we go. I was unsure, initially, whether it was wise to honor these requests, to return only three, four, five days after. Might it retraumatize him? I wondered. I wonder. I turned to Google—results inconclusive. It will, some say, restore him; it will, say others, destroy him. So similar in sound: restore, destroy. I looked up the etymologies, seeking a link. None exists, though both descend from Middle French. Parallel genealogies, untouching. He wants to go to the aquarium, and it will do something to him—something from the Middle French. But there’s no telling what.

—

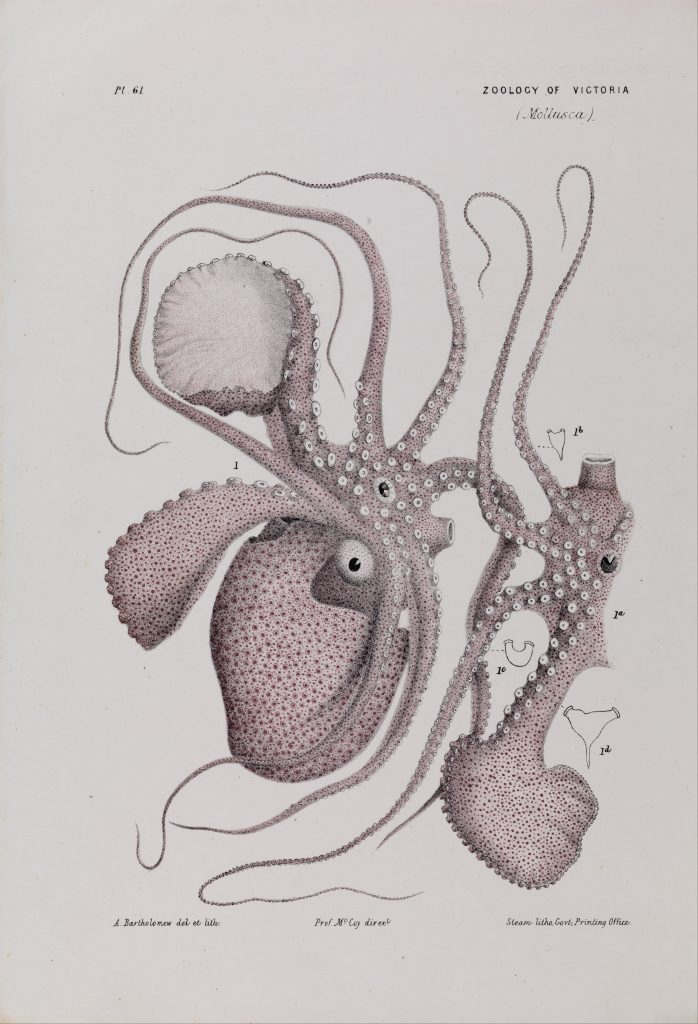

As we peel out of the apartment complex parking lot, it occurs to me that the aquarium might, by now, be closed. I hadn’t thought to check. I don’t now, either. Lately I’m very what will be will be, a defense mechanism disguised as enlightenment. The kid sits up front, as always, though he isn’t old enough. Such rules have seemed ridiculous for years, since his mother died. When we pause at a stoplight, I turn to him to gauge his state. He’s gazing straight ahead, eyes unfocused, vacant. To keep from crumpling, I look to the left. I see, blaring bright like a beacon in the night, a salon window lit up spectacularly from the inside. In a row sit seven women staring into mirrors. Around them seven male figures move, their motion mechanical but not without grace. Some linger by the seated women—snipping, shaping, dyeing. Perhaps administering advice. “Dad,” the kid says. I feel the soft shock of his hand on my elbow. “Green.” “Right,” I say. “Oh.” We go. The parking lot hubbub makes it clear that the aquarium is not closed. Relief screams through me. We park and enter. I watch the kid closely for signs of—what? Fear, life. His face and gait reveal little. He was an opaque child even before he acquired speech—and with it, the power of its absence, silence. Each tragedy that has shattered his short life has remade this reticence, each iteration firmer, more formidable. Before him, I always thought of myself as interested in and attuned to mystery. I put myself willingly, willfully in the midst of things I could not understand. Now I would kill for some clarity. I pay at the front counter. The kid stands still by my side. When the attendant passes me our tickets, I notice the beds of her fingernails, ravaged from fretting, as are my own. I wonder if the tragedy has touched her, too. The city is only so big. I wonder if I should look into some kind of season pass. How often will we make this pilgrimage in the coming months, the coming years? Impossible, now, to imagine the existence of the world so far in advance. The kid and I enter through the turnstile, which devours our tickets and admits us with two successive clicks. He leads; he knows the way. He hurries, almost but not quite running. His breath quickens. Somewhere in the cavern of his chest, a small heart labors a little harder. It’s a sign. But signs say nothing more definitive than silence, though they purport to. Silence rebuffs reading; signs demand it. Does his speed signal enthusiasm, an unburdening, the onset of healing? Or rather anxiety, or mania, or a flamboyant, captivating dread? I keep pace with long strides. The space that surrounds the octopus tank is deserted. It’s as if others know not to stand here—a live disaster zone, though barren of rubble and emptied of the shouts of the wounded. Unimpeded by other bodies, the kid steps up to the glass, presses his nose against it. I go to the informational plaque displayed beside the tank, not that I need to read it. On my deathbed, ask me to recite the text. I’ll sing you every word, unerring. I read it again and mouth the syllables, subvocalizing as if in prayer. The kid has found his comfort. I steal a glance. He hasn’t moved. I approach, shifting my weight to mute my steps. I don’t want him to feel observed. But I suspect I could charge, wailing, brandishing a broadsword, and not disturb him. He’s serene in the way he is only here. Over his head, I see the animal, floating, still and motile at the same time. Is my perception a trick of the octopus’s environment? No—it’s not how other beings look in water. It’s the thing itself, its alien sway. Faceless, yet it stares. I think of the other animals under this roof, none like it. Not the simple finned fish flexing, alone or in droves, from here to there. Not the mammals cursed or blessed to dwell in salt, surfacing for air in which they’ll never thrive. Not even the jellyfish, those translucent, pirrhoueting nearly-nothings. The octopus, unlike these others, is a body, a presence. And, as the plaque has taught me—and will teach me tomorrow, and the day after, again and again—the octopus is, too, a mind, a presence in this other, sadder sense.

—

The next morning, I encourage the kid to do more research into octopi. “Is it even octopi?” I ask him. That seems like a good place to start. He smiles—solemnly, but still—and accepts the task. He asks to be lent my laptop. After retrieving it from my room and clearing the browser history—filled, now, not only with the usual smut, but also with forums on trauma, lists of warning signs for suicide—I hand it to him. Within minutes he’s discovered three schools of thought about the plural: octopi, octopuses, octopodes. “Wow.” I beam. I leave him to his studies. I’m hopeful the assignment might send him, by way of this obsession, back to himself. And I hope—more desperately and futilely—that the prolonged contact with the scientific community’s consensus reality might help to relieve him of the ludicrous notion that haunts him, however repeatedly and insistently I tell him it’s not his fault: that his absence from school one day—taken together with the fact of his innocent, understandable distaste for his schoolmates, who have shown him no kindness—makes him responsible for the murder of eleven among them, struck dead by rounds shot from an M-16 rifle held by a seventeen-year-old boy with a swastika inked onto one wrist, the wrist near the trigger, now dead himself, leaving no one to bring to justice. No one but my son. It was the day of his mother’s yahrzeit. I’d taken him out of school so we could mourn, alone, together. I’d been straightforward with the school principal about this decision. He’d been supportive. I think he’d liked my use of yahrzeit. I suspected the principal was less than fond of me. It was clear from our conversations that he didn’t see why this more-or-less goyish son of a goy should be educated at a Jewish day school based only on the vaguely expressed wishes of his Jewish mother—now buried, unwishing, in the earth. (There is, I might remind the principal, the matter of the matriline. We’re playing by his own rules.) When the day came, the plan was to visit the grave, then the aquarium. It was the kid’s idea. I was thrilled. It seemed to me a sign of healthy grieving, this attunement to his mother as she’d been in life. Sea creatures had fascinated her. She’d checked out books on mollusks and racked up library fines rereading them. She’d sent me National Geographic links to click at work, her emails’ subject lines overflowing with exclamation points. Over dinner, she’d always be bringing up sea life trivia. The kid would listen, awed. We’d often entertained the idea of a family aquarium escapade. But the days pass. We’d never made it happen. We were facing the octopus when I heard. A news alert shook my phone. I looked. Nine dead. All eleven confirmed by the time I clicked through, allowed the page to load. I was struck by the urge to remain still, as if this would stop the body count from rising. I read, scrolled, read. The newspaper from which the alert had originated would not print the words the assailant had said. I would later read them elsewhere: “Die, kikes.” I couldn’t bear to tell him. I’d delivered news like this once before; I couldn’t again. I put my phone back in my pocket. I let him enjoy the octopus. I could hear him whispering to it. Out of respect, I didn’t listen to discern. He came to me when he was done. We chatted about the creature’s coloration, how its intelligence was obvious from its motion; I cited some text from the plaque, which I’d then read only once. The kid tried to move his arms like tentacles. He pressed one to my back and maneuvered his mouth and cheeks to produce a thick, wet, suction cup sound, from which I recoiled with an imitation of the laughter he’d intended to elicit. The news, unspoken, throbbed in my temple. How many dead now? I wondered, not knowing the count was set. In the car, I turned on the radio. A coward, I let him learn it this way. I told him it was fine to cry. Blaspheming against my own unbelief, I thanked God that I did not have to say it aloud. I thought: This failure will not be my last.

—

Soon I begin to question my decision to encourage the whole octopus investigation. It leads to some dinnertime talk. But not of the sort I hoped. Over bowls of boxed black bean soup garnished with crumbled tortilla chips I ask what he’s learned. “The octopus is something people draw when they hate Jews,” he says. I set my spoon in my bowl and let it sink beneath the desiccated chips. “What are you talking about?” I say, though I know. He invites me back to his room to show me on my laptop, which I now lend him for a few hours a day for this purpose. He shows me the images he has discovered. Octopi—or octopuses, octopodes—marked with stars of David with their tentacles wrapped around whatever forces they are said to control. The bright blue octopus embracing the globe—a classic. “Son,” I say, feeling lightheaded, “it’s a coincidence.” He closes the laptop and shrugs. “I mean it,” I say. “It doesn’t mean anything.” “OK,” he says. But why should he believe me?

—

By the next week, I’m fielding calls from the principal. Classes have resumed. All the other kids are back. Why not mine? Why not the kid who never heard the gunfire, who never saw the bodies? Psychiatrists will be made available, the principal informs me. I don’t know how to tell him that the kid’s not ready. That I’m not sure he’ll ever be. “We’re working on it,” I say. Not that I’m showing up where I’m supposed to either. Soon my sick days will be gone—only uncharacteristic corporate kindness has allowed me to use them for this purpose. Then my modest stash of vacation days. And then—what? The next time, at the aquarium, I try to interest the kid in another exhibit. Past the turnstiles, I open the map—I take a new one from the attendant’s desk every time; I’m amassing a collection—and wave it, even as he’s speeding off ahead. “Hey,” I say, “maybe we check out the tropical fish?” He doesn’t turn. “Or this visiting exhibit? The tortoises? It says they’re ancient! It says they’re on loan from somewhere else.” Of course he wants nothing to do with it. He has eyes for one animal alone. Another week passes, and the principal calls again. He wants to arrange a private meeting with me and the kid. Uneasy but struck by a surge of gratitude for the offer of support, I say sure. I start suggest dates when we might come into his office. The options are many—we have nowhere to be. The principal says he’d prefer a less official setting, for the kid’s comfort. I sense that I’m supposed to invite the principal over for dinner, so I do. “This Friday?” I feel myself say. “Delightful,” he says. After we’ve hung up, I realize I’ve invited the principal—a rabbi—over for Shabbat dinner. I rush to the closet where untouched things are kept. I dig out a box of items sentimental and ceremonial. From the depths of the box I exhume candlesticks we were gifted for our wedding. I wipe them down with a rag, scald them with searing water to clear out the ancient remains of bygone wax, and set them in the middle of our now-unused kitchen table. In the box, I find candles that fit, the wicks frayed but ignitable. From the box of lost things I plunder the other necessary accoutrements. My father-in-law’s kiddush cup. A challah cover my mother-in-law knit us. (My ex-father-in-law, ex-mother-in-law? Does the bond persist in the face of death? Does the law?) On my laptop, I begin researching recipes. An hour in, it occurs to me that our kitchen is not kosher. Meat and milk mix freely. We have only one oven, one set of silverware. Is this a problem for the principal? I have no idea. Another man might call and ask. Instead, I call a local kosher deli and place an elaborate advance order, to be picked up an hour before dinner. I go to the kid’s room and knock, await his silence. I linger in it briefly and open the door. “The principal from your school is coming for dinner Friday,” I tell him. “Shabbat dinner. We’ll need to find your clothes. And we’re going to practice the prayers.”

—

On Friday, on my insistence, the kid comes with me to pick up the food. He stares intently out the window. Is he staring at something or nothing? I’ve long puzzled over the possibility of the latter. Isn’t all staring a staring at something, all thinking a thinking of something? But these last few weeks have unsettled my righteous certainty on this issue. Look at the kid: that’s staring at nothing. That’s thinking of nothing. That’s nothing in the flesh. The not-flesh. I’ve begun to think this at the aquarium, watching him watch the thing—the nothing. Nothing, tentacled, spilling out from some gash in the something. Now who’s the one making too much of an animal? At the deli, I convince him to accompany me inside. He stands beside me at the counter and makes the kinds of faces kids are expected to make. As we make our exit, each of us carrying an overflowing bag of food, we approach a bulletin board with a flyer stuck to it which, from a glance, I can tell is for a benefit for the victims. I crouch as if to tie my shoe, let him pass me, and rise, slipping between his body and the bulletin board, obscuring his line of sight. I congratulate myself on my canny parenting. In the car, as I turn the engine on, he says, “I saw.” He looks at me and back out the window, wrapping his arms around the bag of food on his lap. It’s so large it could contain him. “I’m sorry,” I say. I look in the rearview mirror and wish I could see nothing there.

—

The principal is early, but we’re ready. The kid’s in khakis, and I’ve unearthed an unwrinkled tie. We’re standing tableside, practicing the prayers, when the buzzer chimes. “I think you should go get it,” I say to the kid, which, if I had thought of it before this very moment, I would have mentioned earlier. He looks at me, his mouth just ajar, but doesn’t move. In a way I barely recognize as emerging from my own mind, I feel insistent on this point and, though it is unlike me, enraged at this small show of insolence. “Let me rephrase,” I say. “Get the fucking door.” He closes his mouth and goes. I hear the door open, hear his footsteps on his stairs as he goes to retrieve our guest. I go and stand in the front room, eyes locked on the open door. As they enter, the kid in the lead, I spread my arms magnanimously. I mean the gesture’s obscene grandeur to obscure the meal’s possible paltriness. “Welcome, rabbi,” I say. The principal extends his hand, and I offer mine. I expect him to invite me to call him by his first name. All he says is, “Shabbat shalom. Thank you both for having me.” I take his coat to the closet. We stumble through small talk. The kid smiles, is silent. At the table, the places are all already set, and because there is no hiding the source of the food, and I want to make sure he knows it’s kosher—that if I’ve failed somehow, it’s not for lack of trying—I explain this apologetically. I expect him to reassure me. He does not. We take our seats. Before I can invite the kid to say the prayers, the principal divests us of the duty by beginning them himself. I watch and hate his hands on the matches as they quiver over the candle wicks, his lips on the kiddush cup, his hands on the challah cover. None of this is his. But it’s not mine either. Perhaps it’s his more than mine. The event that has brought us all here, this certainly is. The kid, this ruined boy I feed and bring to stare at an alien animal and drag along to errands to impress men I fear—isn’t this being more his than mine as well? As we begin the meal, the principal wastes no time. “I wonder,” he says, speaking to the kid, though I get his gaze, “if you’ve thought about coming back to school.” “Am I even allowed?” the kid says. I choke down my first bite. “Of course you’re allowed,” I say, sputtering. Then, to the principal: “I never told him he wasn’t allowed. I would never—” The principal waves away my concern. His long fingers tilt in a way I read as both soothing and dismissive. “I wonder,” he says, still looking at me, “what would give you the idea that you wouldn’t be allowed.” “Because of the octopus,” the kid says. “We were at the aquarium when it happened,” I say, “looking at the octopus.” I should have explained this on the phone. “He got it in his head that because he was spared, and because of some of his problems with the other kids—that it was, somehow, his fault. The octopus got wrapped up in this. Like it signified something. And now he’s convinced himself that—he started learning about the—the connotations of the octopus, and he—” The principal waves me back into silence. I let him do it. It’s his house, I think, then I remember it isn’t. He proceeds as if I hadn’t spoken. “I wonder,” he says, “why the octopus would forbid you from returning.” “It doesn’t forbid me,” says the kid. His fork falls onto his plate. The clatter cuts me. “Perhaps you can tell me what you mean,” the principal says. “I’m not stupid,” the kid says. “Or insane. I just think the octopus is a sign. That I shouldn’t come back.” “I agree that the octopus is a sign,” the principal says. Now he looks to the kid, who looks up at him. I take a bite of challah and run my tongue over its egg-washed surface. I let the rest dissolve into my mouth to gently gag myself, so I say nothing. My best over the past weeks has been a failure. It’s someone else’s turn. “Perhaps,” the principal continues, extending his palm as if offering my son a trinket, “you have misread the sign.” The kid leans in closer. His elbows dig into the tablecloth. I think I can hear his breath quicken. I might be mistaken. “What does it mean?” The principal’s voice withers to a whisper as he says, “I can’t be sure. But I wonder if you have been visited by the leviathan.” He takes a sip of water. “Are you familiar?” The kid shakes his head. “I wonder if you could fetch my coat.” Whether he means me or the kid, I have no idea. Without waiting to divine the answer, I rise and obey. He pulls a small leatherbound volume from his pocket. He doesn’t thank me. I replace the coat in the closet and return to my seat. I start back in on my food. “Let me read you a bit from the Book of Job,” the principal says. “I know you’ve learned the gist in class. Perhaps not this part. HaShem—God, yes?—is speaking to the long-suffering Job from a whirlwind.” The principal opens the book and reads: “Canst thou draw out leviathan with a fish-hook? Or press down his tongue with a cord? Canst thou put a ring into his nose? Or bore his jaw through with a hook? Will he make many supplications unto thee? Or will he speak soft words unto thee? Will he a make a covenant with thee, that thou shouldest take him for a servant for ever? Wilt thou play with him as with a bird? Or wilt thou bind him for thy maidens? Will the bands of fisherman make a banquet of him? Will they part him among the merchants?” He closes it. “Forgive the translation. A bit old-fashioned, perhaps.” The kid’s lips are, again, ajar, though the sense I get from them now is not like the sense I got earlier. The expression had projected a kind of disbelief. Now it’s more like awe. “I don’t understand,” he says, expectant. The principal laughs—an inelegant laugh, like a less learned man’s. “Exactly,” he says. “The point is this, that before the leviathan, we are powerless. HaShem can tame him, but humans? No. But listen: in the Talmud it is said that, in the world to come, the redeemed shall feast on the flesh of leviathan.” He takes a bite of his food and gnashes his teeth, as if to demonstrate. “There is yet hope,” he says. He swallows. The kid’s hands are now outstretched. “What,” he says, “is the world to come?” I take my plate into the kitchen. I dump the food into the sink and wash the crumbs from the dish. I let the water get hot and run it over my palms. I savor their reddening. How much can a person bear? From the dining room I can hear them whispering. I wonder what this man is telling my son. I try to stop wondering. I turn on the garbage disposal; its gurgling helps. I imagine that it’s not the principal in the other room with my son, but the octopus, freed from its enclosure, in a chair or the air, floating, wise. The two together, murmuring in a language I can’t know. If I close my eyes now, might I see not this scene, and not my eyelids’ other side, but nothing? It has never worked before. I know it won’t tonight and won’t tomorrow. But that’s not to say it never will.