I grew up going to a Jewish summer camp outside of Yosemite National Park. I spent most of my childhood summers there, returning as a young adult to work on staff. An archetype for Jewish hippie summer camps, it was there that I learned about tikkun olam, in theory and in practice. As one might expect from a camp rooted in the San Francisco Bay Area Jewish community, the camp holds progressive ideals and teaches a deep love and care for self, community, and the earth. It was there that I also realized that G-d can be found in all things, living and non-living, and felt my strongest spiritual connection when swimming in the river or backpacking in Yosemite. I learned and wholeheartedly embraced the American-Jewish liberal ideals of tikkun olam especially as it was tied to environmental conservation and protection. A passionate environmentalist (in no small part because of camp), I felt that protecting and restoring wilderness and minimizing human impact on the earth was not only an imperative ethical goal, but also a spiritual guiding force.

My camp was one of the earliest American-Jewish institutions teaching and practicing a form of what is now widely known as “earth-based Judaism.” Followers of earth-based Judaism believe that nature and the natural world is central to Jewish history and practice—after all, G-d gave the Israelites Torah in the wilderness, and the Jewish holiday calendar is centered around agricultural cycles. Rabbi Mike Comins argues that “many Jewish practices can be far more effective when practiced in wild nature,” calling for an ethical and spiritual imperative for Jews in this time of climate crisis to “unearth our wild roots.”1 Non-profit and grassroots spiritual communities that connect Jewish spiritual practice to ecological sustainability have grown in the past few decades, particularly on the West Coast. These efforts—Wilderness Torah; Adamah and Urban Adamah; and the Jewish Outdoor, Food, Farming & Environmental Education Network (JOFEE)—include programs for all ages, from summer camps to residential farming fellowships for young adults, to outdoor education training, to celebrating Jewish holidays on the land (like Passover in the Desert or Sukkot on the Farm). These organizations have won numerous Jewish institutional awards and are praised by Jewish establishment leaders as innovative ways to connect young Jews in particular to their Jewish roots, community, and progressive visions for the future.

Not always present in institutional publications but still notable is earth-based Judaism’s discursive and communal link to calls for “Jewish decolonization.” What is meant by decolonization here is often varied and vague. For some, it is reckoning with Jewish people (particularly or exclusively white Jews) as settlers in both Israel-Palestine and North America; for others it is moving to reclaim earth-based practices, like the agricultural festival of Sukkot “in diaspora” as explicitly anti-occupation and/or anti-Zionist.

However, in recent years a popular discourse has emerged that complicates claims to Jewish decolonization. Some (mostly Zionist Jews and their supporters) say that Jews are the indigenous people of Israel-Palestine; decolonization therefore would mean restoring Jewish sovereignty over the whole land (West Bank, Gaza, Jerusalem), both through Jewish political control via the Israeli state and also by restoring ancient Israelite earth-based practices and relationships with the Holy Land. That includes what are understood as the original “Hebrew” ways of life: agricultural festivals, farming certain crops in certain ways, and sacred prayer connection with land.

At a time in which criticism of Israel as a settler-colonial2 state has moved outside of academic niches and into broader popular conversations, “Jewish indigenists”—who do not self-identity as Zionists—combat this framing by suggesting the Roman conquest and destruction of the Second Temple was the original colonization; the Jewish people’s return from exile and diaspora is an anti-colonial liberation, against both the Romans 2,000 years ago and the British more recently. They argue Israel is a decolonial, rather than settler-colonial, state. Their framing raises a somewhat troubling question: what are the problematics of return?

At the risk of sounding like a cranky academic, I find the discourses and institutional efforts around earth-based Judaism, tikkun olam, and Jewish decolonization still lacking—even as I have actively participated in building them.

Tikkun olam circulates through both of these discourses, regardless of their political bent. Both decolonial and settler-colonial ideologies grapple with issues of repair and restoration. Mainstream American Judaism has mostly interpreted tikkun olam in environmental contexts to mean restoring and repairing the earth to an earlier, more pure form, through ecological restoration and conservation. Tikkun olam justifies restoring the land itself through organic farming, permaculture, or wildlands preservation; repairing Jewish spiritual connection to the land and each other and healing communal trauma; or even resurrecting a more glorious Jewish past—whether in the olive or wheat field, the walled city of Jerusalem, or the streets of Brooklyn. That Jewish past may be integrated with other communities or stand alone, but it is recognizably and distinctly “Jewish” in spiritual, cultural, and/or social practice and relation. Zionists, non-Zionists, and anti-Zionists have all participated in these forms of romantic, nostalgic populism—it is not limited to Israeli settlers, although the power structures that inform and are shaped by such discourses are not equal in their intent or impact.

—

I study issues of settler-colonialism, indigeneity, and decolonization both in Israel-Palestine and the American West, particularly my home in northern California. I care deeply about repair and building Jewish struggle for a better future for ourselves, our comrades, and our lands. Yet, at the risk of sounding like a cranky academic, I find the discourses and institutional efforts around earth-based Judaism, tikkun olam, and Jewish decolonization still lacking—even as I have actively participated in building them.3

As different institutions and ideologies are at play here, I do not mean to collapse everything into one problematic basket. Instead, I’d like to examine some multifold issues, some present in multiple of the aforementioned efforts and some not, some that point to the fatal flaws in our current understandings of tikkun olam and decolonization, and others that generate exciting possibilities for us to repair better together.

First, nearly all of these efforts, intentionally or not, reinforce a false binary dominant in European Christian thought: the nature/culture divide. In this binary framework, nature exists physically and ideologically outside of human civilization: the vast desert, the dark forest, the barren plains. Nature is forbidding and yet seductive. It is a place for spiritual redemption, yet also spiritual punishment. To be a productive member of Christian society, one must bring Nature to heel, both the space itself and all peoples upon it.

As the European ruling class violently transformed the continent from feudalism to capitalism, the church and elites brutally enclosed common space, claiming that nature was a space for witchcraft and sin. This enclosure of the commons, as Silvia Federici argued in Caliban and the Witch, profoundly decimated women’s autonomy in particular, as the moors, forests, and other commons were centrally important for women’s economic independence and communal and spiritual practices. With the translation of the King James Bible in the early 16th century, wilderness, and more specifically “wasteland,” became understood as land G-d had made desolate as punishment and must be repaired and redeemed to bring its stewards into Christian grace.4 English Enlightenment thinkers, most notably John Locke, used this Christian idea of wasteland to justify capitalist ideas of productive labor and property as land that is “properly” cultivated. These ideas were not limited to internal European capitalist transformation, of course; they undergird the violence of settler-colonial expropriation and the racial violence of slavery in the Americas.

Nature as the premier site of Jewish decolonization also relies on racist tropes of indigenous people and indigenous identity. European settlers did not see Native Americans as capable of civilization; they were less-than-human, enmeshed in the natural landscape as deer or oak trees. They were just as available for destruction, leaving their land and people to be transformed into property and exploited as capital. Jewish decolonization and earth-based Judaism proponents who envision a return to ancient Jewish roots that are more connected to the land believe in the authenticity of such “roots” in part because of Western notions that erase any line between “nature” and “indigenous” and conflate indigeneity with being “uncivilized.”

What comes to mind, then, when Zelig Golden, the founder of Wilderness Torah, lamented how humans have been “removed” from nature and must “return?” “As a disproportionately urbanized people, Jews exemplify the modern trend toward nature-disconnection,” Golden wrote in 2010. “…Until the very recent establishment of the State of Israel, the greater part of the Jewish people have been cut off from an enduring land connection for the better part of the last 2000 years.” Here we see the idea of nature only as that which is separate from culture, with current redemption only coming from resurrecting what Golden calls “aboriginal Jewishness,” which can only be in natural—not urban—settings.

Yet indigenous people of the Americas have always called cities home, although for some Native Americans today, urban life was violently forced upon them. Tommy Orange, in his unsparing love letter to his hometown (and my current town), Oakland, mused: “Cities belong to the earth. Everything here is formed in relation to every other living and nonliving thing from the earth.”5 Nature is not something that occurs outside of the city—cities are in relationship to the land they’re built upon and the people who live there.

I love being among trees, but I am not inherently “more Jewish” in a forest than I am in my apartment. (And who even gets to define what a forest is, anyway?)

I am a lifelong city dweller. So were my ancestors in Bialystok, Krakow, London, New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago. I love being among trees, but I am not inherently “more Jewish” in a forest than I am in my apartment. (And who even gets to define what a forest is, anyway?)

In no small part, settler-colonialism fuels the thought that city-dwelling Jews need to turn off their cell phones and go camping to be truly Jewish. As settlers successfully eliminate native people, they then turn to “indigenizing” themselves through cultural conquest of the landscape that they recast as ancient. White supremacy and antisemitism pushes the canard of the urban Jew as evil, a “rootless cosmopolitan” with no loyalty or place in the world. These two trends are particularly evident in Zionist political thought as well as in the material structures of the Israeli state. Such examples include the Zionist formulation of the Sabra—a “new Jew” reborn in Israel as a romantic, buff farmer in love with the land of Israel as opposed to a weak urbanite; and the rise of eco-tourism projects in Israel that use archaeology to directly link ancient Jewish agricultural practices with contemporary Israeli environmental stewardship.

Yet many earth-based Judaism practitioners explicitly see the potential of landed Judaism as an anti-Zionist project and actively criticize the antisemitism present in Zionist “new Jew” conceptualizations. How, then, is the implicit or explicit denigration of urban life so present in much of this rhetoric? Is this not another form of internalized antisemitism so much of the Jewish left is working against right now?

Finally, let me return to one particular place at my camp: a jumble of boulders outside of the dining hall, a popular spot for younger campers to climb and play. Some of the rocks have a series of large round grooves ground into them. The residents of the Central Sierra Miwok village that had been where my camp is now used these chaw’se, or “grinding rocks,” to prepare acorn meal, grinding and then washing the bitter flour through the series of holes to leach out the tannins. Acorn meal was a staple food of Native Americans across California, and remains a culturally important food today. The camp director of many years has a robust relationship with the Tuolumne Band of Me-Wuk Indians. Campers learn about the history and present of Indigenous people at our campsite, and the former director has spent decades collecting and preserving Indigenous artifacts found at camp. He even used to collect huge bags of acorns from the camp’s oaks to bring to annual tribal festivals.

My camp is not unique in educating youth about Native American history, particularly now when new calls to publicly reckon with the genocide of Indigenous people are gaining support in settler culture in California. Indigenous organizing has successfully led to the removal of a statue in San Francisco celebrating colonial conquest and to removing the name of Junipero Serra, architect of the California missions and Native genocide, off of a building at Stanford University. If one believes in the now-common call that “decolonization is not a metaphor,” however, then acknowledgment of Native history and apologies for past violence is just a bare minimum first step. Is decolonization that does not actually move towards restoring sovereignty of Native lands to Indigenous people actually decolonizing at all? And when dealing with Israel-Palestine, how does one determine who is indigenous?

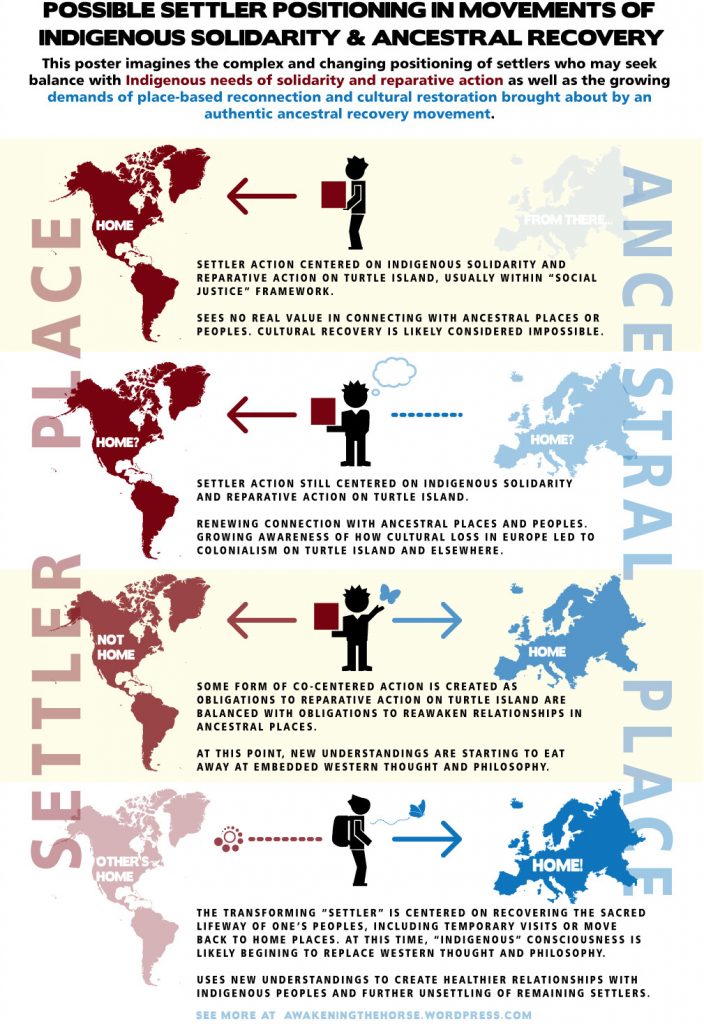

And what would non-metaphorical decolonization look like for earth-based Judaism and its practitioners? For answers, we can look past Jewish decolonization efforts to the wider, growing trend of “white decolonization.” In order to fully repatriate Native land in the Americas, some advocates of “white decolonization” support simplistic ideas of settler return. I take issue with this proposal. First, it relies on often simplistic or outright false ideas of European traditions. Whatever “sacred lifeway” is “recovered” usually looks like an amalgamation of varied paganistic practices heavily reliant on an appropriation of Native American spiritual rituals (like smudging or sage burning) recast as “indigenous European.” Never mentioned is the long and flourishing history of Catholicism or Protestantism as indigenous to Europe too—seeing Christianity as a European religion doesn’t fit a narrative that white people are oppressed by whiteness.

Second, much like the use of “Celtic pride” or “Norse pride” symbols and claims by white nationalists, the idea of white settlers connecting and returning to their European heritage reifies racial essentialism and even re-centers whiteness as dominant in the national (and global) racial hierarchy. If Europe is by and for Europeans, that justifies Europe’s violent border policing and its long history of expelling and oppressing the Other.

Third, the idea of every person, or to return to our topic at hand, every Jew, returning to “where they come from” is what Zionists call for—an ingathering of all Jews in the world. Jews living in and migrating to historic Palestine, what is now the state of Israel, as they have for millenia, is not the issue. Political return to Israel, however, is predicated on an ethnonational idea of citizenship and territorial nation-statehood, requiring the ongoing violent dispossession of Palestinians as well as the negation not only of Jewish diasporic place but also of the varied languages, cultures, and spiritual practices that have emerged as Jews called the whole globe home. A “return” for white Ashkenazi Jews to Europe is not possible. Even physical re-immigration would not bring back what Alain Broissat and Sylvia Klingberg termed the “vanished Yiddishland…a blank, a void, an abyss created by the earthquake of history.”6

Yet I also remember leaving the Indigenous Sunrise Ceremony on Thanksgiving Day on Alcatraz Island, hearing an Indigenous man drumming and chanting to all of the white people boarding ferries to leave the island, to keep going even farther: “Go back to Germany… Go back to England…” Is it even possible for me to heed that call?

—

There are some things that cannot be repaired—that is, they cannot be made fully whole again. Yet tikkun olam’s popular translation in liberal American Jewish discourse as “fixing” or “repair” can be rethought and rearticulated. What are our Jewish ethics not of repair but of relationships and relationality? How can we imagine relationships of “belonging to the land” instead of “the land belongs to me” that are rooted in our own traditions and communities, without appropriating or romanticizing? What would it mean if I knew that California was not empty, but full—of Native people, in the past, present, and future—and still decided to keep my home here? Is there room enough through relationships for all of us to have home?

How can we imagine relationships of “belonging to the land” instead of “the land belongs to me” that are rooted in our own traditions and communities, without appropriating or romanticizing?

Getting away from theoretical musings offers some hopeful, practical efforts. Some Jewish farms have begun to pay land taxes to the indigenous nations on whose lands they are working. Urban Adamah in Berkeley donated to Sogorea Te’ Land trust in Oakland for Tu B’Shevat, and Linke Fligl, a queer Jewish chicken farm in New York, pays 10%of their sales to Schaghticoke First Nations.

Inspired by such efforts, I am working with academics in my field to institutionalize such land taxes into our fundraising efforts whenever we host conferences or workshops. The growth of Indigenous land trusts, when tribes (federally recognized or not) gain conservation easements or even ownership over ancestral lands, have offered up clearer paths for material redistribution of resources into Indigenous stewardship. Land trusts are not a panacea, but they are a tool in the toolkit for Indigenous people, particularly unrecognized tribes, to navigate our current capitalism and settler-colonial structures in order to have access to and sovereignty over their ancestral lands.7 Yet even these financial redistributions, meaningful and material as they are, are not full reparations or repair.

I think a lot about what my Jewish summer camp would look like decolonized. Would my children still go there to make friendship bracelets, swim in the river, sing old Jewish and American folk songs? Will they still camp in Yosemite National Park, which exists thanks to John Muir, an anti-Native racist who used national parks to kick Native Americans off their land? Is there anything that can be repaired and redeemed from these Jewish practices of connection in nature, and how will I teach my children about tikkun olam, in our home? I don’t know, and I can’t answer these questions alone.

- Rabbi Mike Comins, A Wild Faith: Jewish Ways into Wilderness, Wilderness Ways into Judaism, Jewish Lights Publishing: 2007, pp. 7–8.

- I define settler colonialism as distinct from colonialism as according to Patrick Wolfe. Settler colonialism has colonizers that aim to stay, and structural elements that persist beyond invasion as an event.

- I have been an organizer for anti-Zionist organizations and anti-occupation and BDS campaigns, in the United States and Israel-Palestine. I am also a former moderator of the Jews for Decolonization “Jewish leftbook” Facebook group.

- Vitorria di Palma, Wasteland: A History, Yale University Press: 2014.

- Tommy Orange, There There, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group: 2018, p. 11.

- Alain Brossat and Sylvia Klingberg, Revolutionary Yiddishland: A History of Jewish Radicalism, New York: Verso Press, 2016.

- See Beth Rose Middleton (Manning), Trust in the Land: New Directions in Tribal Conservation, University of Arizona Press: 2014.