I visited Moran Sanderovich in her studio on a beautifully perfect date: two-ten-twenty-twenty — before we two knew where 2020 was going — to twenty seconds of hand washing and two meters of distance between us. We are in the midst of a global crisis, inflicted by a virus that attacks bodies and leads to illness and deadly complications. We try to minimize contagions by avoiding touch, depriving ourselves proximity with loved ones. When I reflect back on the conversation Moran and I had in her crowded studio, I recall the studio full, with bodies-of-work, intimately surrounding us, while we were talking about bodies, transformations, disgust, nature, manipulations, superpowers, legends, and traumas. What kind of traumas would a lack of touch trigger?

I visited Moran Sanderovich in her studio on a wet, grey, stormy day. Entering her studio, we are met with amputated bodies covered in long, shiny locks of hair, laying on the floor. They have red, open wounds. They are lying lifeless, but at the same time look uncannily alive. Their glaring plastic eyes look upwards, toward us.

I must carefully pass between the laying bodies to take my place on the guest’s seat: a black office chair that stands parallel to the windows looking outside.

Moran sits on another office chair that stands next to her desk, on which her computer and smartphone rest. Her smartphone has a red plastic cover in the shape of a crab. It is typical of the way the artist creates hybrid totem objects out of technological gadgets; artificial representations of the living, natural, wild, or animalistic; and plastic, which in her handling makes grave matters ridiculous, playful, ironic, seductive.

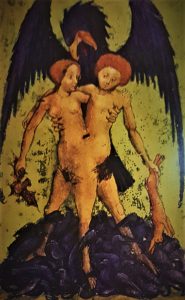

A big mirror hangs on the wall behind the desk, surrounded by images. There are photographic works, featuring the artist performing her pieces, wearing the masks and protheses she creates. There are also ethnographic photographs, depicting abnormal bodies, or bodies transformed in tribal or religious ceremonies, and reproductions of old artworks showing hybrid bodies. These images offer an intensive inspiration-map, contextualizing the artist’s production.

The mirror reflects what is behind us: a very full gallery construction. An oversize sculptural body, with multiple tendrils, finds its rest there.

SinceI have visited Moran in another studio before, I imagine how she moved the studio, packing and unpacking all of those creatures. The moving truck must have become an ambulance, a transport crew — carrying stretchers from the battlefield.

On another wall hangs the artist’s weapon arsenal, of objects that seem to grow living tissues: a gun, made of a crutch; a skin-covered smartphone, connected to a skin-covered selfie stick and a primitive-looking whip; a mask hanging on a very long needle (which actually happened to injure the artist several days before. She was still on antibiotics when we met); and some cables that look like inner organs of some kind. One of them keeps dropping down during our conversation, which makes it seem truly alive. And opinionated.

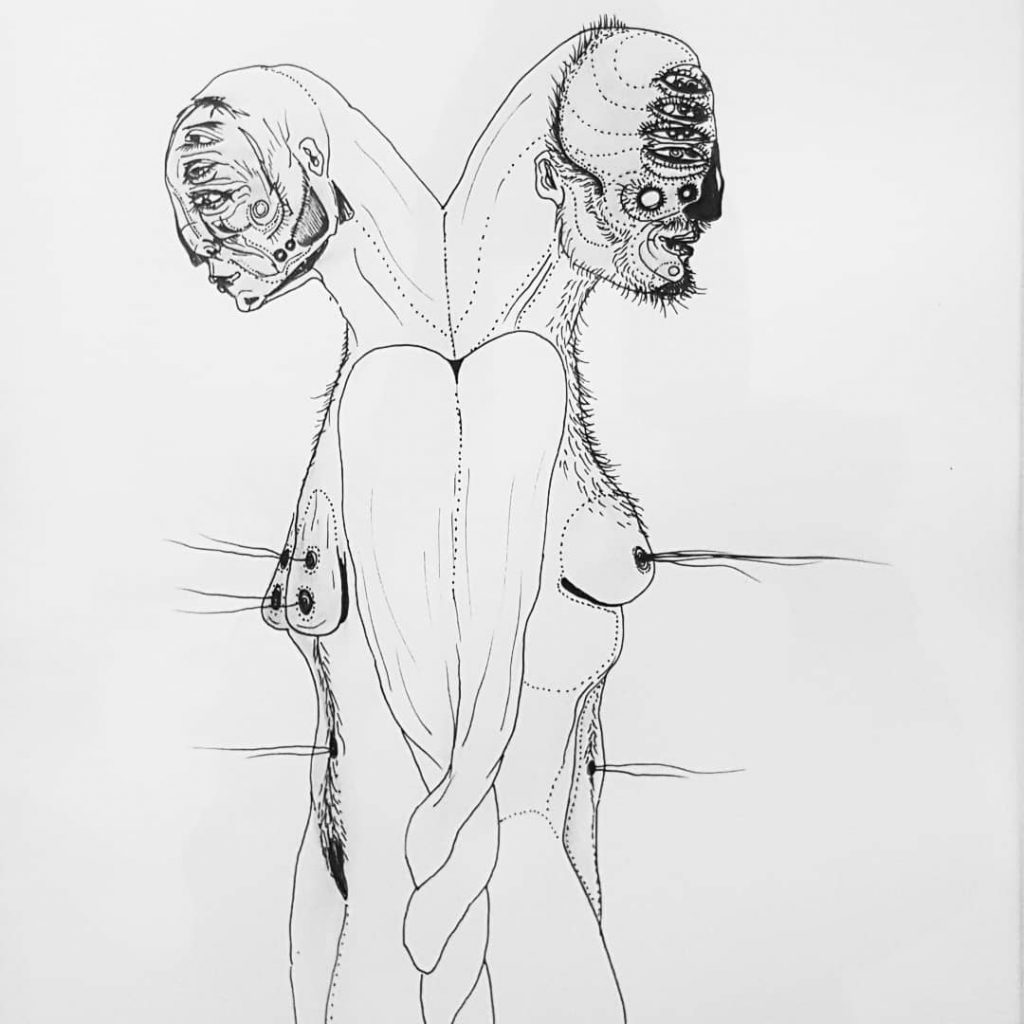

“From pain and trauma grows an otherness,” Moran explains, talking about her works – and about herself? Since she performs in many of her works, it is sometimes difficult to differentiate. She is interested in “transformations” that take place following a “trauma” and talks about a “unique power” that evolves out of a trauma. She devotes her works to this power, hurt, and otherness. Many of the figures she creates have female sex organs. Some have male organs too. The bleeding vulvas often seem violently cut, while the penises perform aggressive attacks. Yet “it is less about victimized femininity, but about the power of the other,” the artist says.

Historically, women were posed as men’s other, I suggest. “We need to leave behind the conception of ‘only man’ or ‘only woman’,” Sanderovich claims, thinking beyond such binary categories. “The disgusting has a power, an intensity,” she claims further. Disgust often rises while confronting something uncanny, something that evades categories: dead or alive? Human or beast? Male or female? The confusion could stun, we agree.

Discussing the disgusting leads to the importance of nature: “Nature saved me, the woods,” she tells, pointing to the cultural repulsion from nature, the disgust from the physical body. “There is no ‘being dirty’ in nature. What is ‘being dirty?’”

Body hair is a key example: we try to control it, to cultivate it, or to get rid of it in order to comply with aesthetic ideals and standards of gender, and in order to differentiate human from animal. And indeed, the artist works a lot with hair, and with a lot of hair – with real hair, as well as with artificial hair. She makes figures that are fully covered with hair, and she talks about girls covered with hair all over their bodies in India, where physical abnormalities are considered sacred, against which I am reminded of the painting depicting a bearded woman breastfeeding.

Sanderovich thinks in mixtures and in contradictions: she is drawn to the natural, as she is to the artificial. In her production, therefore, she works extensively with silicone. This is cyborg-thinking, to borrow the term from Donna Haraway and her Cyborg Manifesto (1985), where the scholar promotes cyborg feminism as a way beyond socialist-feminism. As a neutral isolation material, silicone is as distanced from nature as possible. Yet Sanderovich applies it to mimic natural appearance. It is a deliberate manipulation: Sanderovich strives “to create nature, anew, from silicone, in urban environment.” I must here think of the role silicone plays in aesthetic medical industry, for producing implantations, and in the sex industry, for offering protheses. “A realistic black silicone dildo (9 ¾ x 2 ½ in.)” stars Paul B. Preciado’s Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era (2008), for example. Preciado takes testosterone as a drug, in a philosophical experiment the author runs on the body, being his own guinea-pig. In the autobiographical parts of the book, the author reports the effect taking the hormone has on his love life. The silicone dildo plays an important role here, as an additional, external organ of Preciado’s body, transitioning to masculinity. Industries use silicone to produce realistic-looking perfections of sex organs. Yet Sanderovich uses the same material to create fantastic, wounded, amputated bodies.

Moran Sanderovich, Untitled, 2016. Photo: Hadas Tapouchi.

Sanderovich creates wounds. Beautiful, amazing, stunning wounds. She wants “to look into the body, under the skin,” she says. “[…] the skin being the largest and most public organ of the body and therefore the main platform for somato-political and performative implantation and agency” — writes Preciado, in parentheses, in the context of beauty treatments and “Politics of Care”. “Why should our bodies end at the skin, or include at best other beings encapsulated by skin?” asks Haraway. Sanderovich seeks sensitivity and fragility under that politicized, nationalized, gendered, and aestheticized skin. She claims the “power of being an emotional being.” Instead of repressing emotions she calls for an emotional “deepening.” I ask her if she wants to heal those wounds, if her works should take their audiences through a process of recovery, to which she responds in the negative: “I want to awake, not cure.” “Show your wounds,” called conceptual performance artist Joseph Beuys in 1976. He was wounded at the Second World War, as a soldier serving the Nazi army. As an artist, he was often taken as shaman, working with natural materials such as beeswax, fat, and honey. In An Apartment on Uranus, Preciado writes about “the courage to look straight at the wound,” describing homosexuality and transsexuality as a sniper that plants a bullet in children’s hearts. Sanderovich would have us celebrating wounds. We should address the wound as “a fabulous place,” she says. Under this logic, healing — which would be camouflaging, hiding, suppressing, and successfully erasing, like in a plastic surgery — is not her goal.

Sanderovich invents new humanoid bodies, makes them from artificial materials, and gives them life-like appearance. “I am interested in creating inorganic life,” she says, “in the human wish to mimic — to be God.” “[…] self/other, mind/body, culture/nature, male/female, civilized/primitive, reality/appearance, whole/part, agent/recourse, maker/made, active/passive, right/wrong, truth/illusion, total/partial, God/man,” Haraway lists dualisms that “have been persistent in Western traditions; they have all been systematic to the logics and practice of domination of […] all constituted as others.” Haraway’s list of dualisms captures well what Sanderovich’s hybrid works evade. When Sanderovich creates new bodies, she creates them wounded, amputated. Amputated bodies gain new abilities, in their struggle to find their ways, which is, once again, unavoidably unique. “Handicap interests me,” she says. People with handicap become exemplary cyborgs, with their implants, which give them superhuman abilities, to jump higher with artificial organs that do not tire. “Perhaps paraplegics and other severely handicapped people can (and sometimes do) have the most intense experiences of complex hybridizations with other communication devices,” notes Haraway. Sick people today are in a cyborg state too, when a machine animates them into breathing. The sick are animated into living by a machine, whereas the handicapped animates the machine into life. “In the future, there will be no creatures like me,” says Sanderovich, “there will be a chip” — inserted into brains and ‘correcting’ dyslexia. Are people with dyslexia and other handicaps an endangered species? I ask her in return. Then, in a science fiction futuristic dystopian turn, we would need to clone them in the lab by their genes.

“Legends, myths, are stories about bodies,” traumatized, other bodies, Sanderovich reveals to me. Just think about superheroes of any kind, and their special physical abnormalities. Superheroes and their superpowers “grow out of trauma,” she notes. It is actually a repeating pattern in human storytelling, she says: “superheroes are our contemporary mythological figures…Why do we need them [those legends, myths and stories]?” She asks, in fascination. Why do we need to send strange bodies as far away as possible, to fiction, fantasy, fairytales, and myths? I ask. It is their “task to mirror the self,” answers Haraway. Sanderovich sees here the possibility to identify “through the body” and the bodily experience of listening to a story — about a body. Since all stories are eventually about bodies, I arrive at a strange question, new to me, and burning: what is then, actually, the relation between body and life? “The scary becomes sacred,” Sandarovich notes. And with my art-historical education I must immediately think of Jesus Christ. From all the morals, preaching, and lessons, it is the crucified, tortured, broken, and bleeding naked body communities of believers remember, depict, and worship. And again, Haraway: “Cyborg writing is about the power to survive, not on the basis of original innocence, but on the basis of seizing the tools to mark the world that makes them as other.” Sanderovich’s practice is therefore cyborg performance.

In her works, Sanderovich offers new myths. Her grotesque, strange, fabulous creatures have stories to tell. While the artist was working toward a solo exhibition titled “Disembody,” in the context of celebrating “Jewish Days” in Chemnitz, a German town with a notorious neo-Nazi profile, a new group appeared. Their story is of an old, militant, religious tribe of God-devoted warriors-hunters who have developed advanced technologies and sophisticated sacrifice methods to protect the welfare of their people. The strange, fictitious tribe that Sanderovich depicts is not so different from contemporary human societies. The artist ironically reminds us that we are still invested in military conflicts, religious territorial wars, and violent forms of oppression applied by bodies against other bodies, be they national others, ethnic others, gender others, or species others.

Here is the story of a girl, born to this tribe, with hair covering her entire body, setting her fate, as a fabulous other:

In the tribe at least 1 of 20 girls was born with her entire body covered with soft hair. These girls were treated by the tribe differently, they were believed to have a special connection to God. They used to be covered in flowers and jewelry and had special days of the year where they were celebrated.

When they were 8 years old they were given to the god as a sacrifice. There was a big ceremony in which they went through a surgery. The priests of the tribe used to cut off the arms and legs and torso of the girl and connect the vagina to the head. By using a special machine that was connected to a crystal stone, they screwed the stone into the skull until the brain, in the area of the third eye. In the area of the sex part, they cut with a special knife and put inside a vibrating machine. They believed that the vibration of the machine will call the god and that the god will enter through the sex part and go out through the crystal. And in that the god will scan the people of the tribe through the body of the girl, and know how to guide them better.