Over a series of conversations about Tobaron Waxman’s current projects, which range from interdisciplinary performance to community-based archive activism, to international queer and trans curation, PROTOCOLS guest editor Ariel Goldberg and Waxman decided to show work that embraces the medium of the world-wide web and its attendant screens. What follows is a text co-written between Goldberg and Waxman, where quotes from interviews with Waxman are interspersed with their artist statements. Goldberg’s observations aim to contextualize three artworks on timelines of the techniques of both internet and trans life, asking where and how projects were first seen and made.

Trans.genre.anagram, Peytach Eynayim, and Amidah: Mincha were made circa Y2K. At that time, Waxman was living in Chicago in an intergenerational orbit of queer and trans masculine people. There was not, like today, an enormous younger generation of trans people who are connected and “witnessing each other through Instagram and Youtube.” Furthermore, art made by trans people was not yet included in the canon-making enterprises of Western art history.

The net-art pieces presented here were made fifteen to twenty years ago and possess movement I associate with dissonance. In these artworks, the browser interprets the javascript code, which animates the image in ways that are specific and interactive. The choice to use coding to create artworks comes from a time when art on the internet was mostly known by those who used these tools, “often in ways contrary to their initial intended use, ways contrary to military industrial complex.” Similarly, cultural understandings of trans life were mostly known only by those who lived them.

Cue Shu Lea Cheang’s born digital piece Brandon from 1998-1999, the first ever net-art commissioned by the Guggenheim and now archived on its website. Brandon is a groundbreaking, innovative work that engages the story of Brandon Teena’s life and legacy. Luminaries such as Aureia Harvey, Jordy Jones, JODI, and Cheang shared creative community as they experimented with coding and themes of embodiment. Cue gigantic grey boxes of desktop computers and their attached hard drives. Cue the invention of the USB key. Tropes of visual trans culture anticipated by curators were often limited to porn and drag. Curatorial expectations often took shapes that Waxman could not meet: “monologues, representational portraiture, [and again] drag kings.” Rarely did a single venue or curator provide context for their respective audiences that would permit them to hold the works without imposing simplistic or ignorant expectations. “I was always presumed to be Yentl,” Waxman recalls, “…the emotional range of the tropes was always about kitsch or trickery or tragedy.” Waxman tells me “there was space either for heteronormative imagery or unspoken, verboten homoeroticism.” Cue the flow and rupture of assumptions: trans inside queer inside gay inside straight worlds. When not explaining their work through developing a vocabulary of trans references, Waxman found themself forced to justify the Jewish references. On multiple occasions Waxman’s works were censored or pulled from exhibitions and galleries for fear of backlash.

Trans and Jewish cultures and languages of embodiment continue to change and grow. Trans.genre.anagram, Peytach Eynayim, and Amidah: Mincha have never been exhibited before in a gallery context as a suite of browser experiences. Versions of the photographs on which Amidah:Mincha and Peytach Eynayim javascript animations are based have been exhibited and written about extensively. In 2006 (a different linguistic landscape than the one in which I type now), visionary artist and curator Lawrence Brose bravely curated one of the first exhibitions to feature works made mostly by critically acclaimed artists who identified as transsexuals: “Deviant Bodies 2.0” at CEPA Gallery, Buffalo, New York.¹ Waxman recalls Brose originally offered a solo show but Waxman instead recommended artists to be exhibited together as a group. Waxman felt there was a “political imperative to exhibit more TG/TS (transgender/transsexual) artists.” Despite the groundbreaking concept of the exhibition, all but one of the gallery’s usual funders bailed.

This exhibition was a triumphant success, despite such a hostile climate. Brose included the large format prints of Amidah triptych as well as multiple other large format prints of Waxman’s works with Jewish imagery and trans masculine bodies, all of which were printed at CEPA Gallery’s facility by master printer Sean Donaher. This is but one rich and layered story Waxman has relayed to me over the phone. We continue the conversation through a similar style of narrative captions for these three pieces, each represented with a still image that links to the work in a new window. A link for more information on each of the work’s exhibition and publication history is provided in each caption. Consider this the beginning of a project to record “a certain radius in queer and trans histories of the local” in Waxman’s works. Consider this resistance against the historical routine that makes artists and culture workers at the margins beloved only once they are dead.

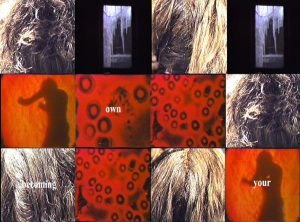

trans.genre.anagram (2001)

trans.genre.anagram is composed of stills from VHS; a phrase continually reorganizes itself in four sets of images, each with a specific word assigned to it. The resulting anagram poem generates different iterations: father/your/own/becoming; becoming/your/own/father; own/your/own/becoming; your/becoming/becoming/father; anastrophe without end. This was one of Waxman’s first attempts at expressing trans temporality through cinema and the internet. The sequence of four horizontal squares cycles through images (some without the associated word, at varying speeds).

The images and corresponding words are: window view of a gigantic icicle (father), a microscopic view of blood cells (own), thermal imaging of a boxer’s silhouette (your), and Waxman’s pre-transition, waist-length hair (becoming). The images were from footage Waxman made on video and from a National Geographic VHS tape given to Waxman by celebrated Canadian film and video artist Colin Campbell, highly influential throughout the 1970-2010s and a teacher of Waxman’s in college. The numbers behind the computer programming running the piece, like other works of Waxman’s from this time, incorporated gematria. At the turn of the century, zines sent through the mail and email listservs were shifting away from being the only way for those on the transmasculine spectrum to get information. Waxman recalls trans people were sharing resources, medical information, and practicing mutual aid on the internet via LiveJournal. Trans life on the internet was not yet “a gaze predetermined by the Instagram square.” Furthermore, the internet was not a topography of social media templates, of data farmed by big business, or strewn with ads: “We were using the internet as message board, as community center outside of bars/nightlife culture, to exchange info, resources, healthcare, relationships, especially those in remote locations or those housebound, or those who used chat rooms, etc., to expand their somatic/empathic experience sexually. All of these building blocks are still there, but under more layers of obfuscation, including selling and being tracked.”

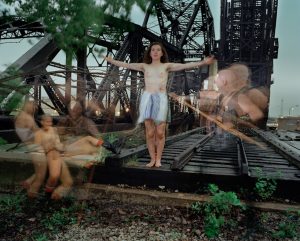

Peytach Eynayim (performance for large format camera), 2000

Peytach Eynayim, this performance for photo, happened the day before Waxman’s waist-length hair was cut, and head was shaved, in the performance installation Opshernish. The image may seem like documentation but was a carefully timed, site-specific choreography for large-format film camera. In an artist statement for the piece, Waxman details: “the protagonist is in a rapturous scene that references Chagall’s crucifixion paintings and the legs of Pierre Molinier.” Waxman interprets the piece as “developing a trans image vocabulary, not using the pre-existing vocabulary.” Waxman, originally trained in art history, explains, “Chagall is referencing the canonical art history (European) of the stations of the cross: the scene of the holy lance, in which the Christ figure is pierced in the side by soldiers, water pours out instead of blood, proving to the soldiers that he was as he claimed, both mortal and divine.”

What does it mean to become an image and idea in the eyes of others when the idea of a trans body was so refused — socially, legally, halachically — in the late 1990s and early 2000s CE? Waxman recalls: “The binder as a garment did not exist. You couldn’t just order a binder online and then have top surgery and give your binder away.” The figure in the left foreground of the photograph is binding using an ace bandage. “People engineered their own [binders], depending on size and access.” In an artist statement for the project “Peytach Eynayim,” Waxman explains that the “name implicat[es] God as site” and “means ‘(the place of) Open Eyes’ in Hebrew, i.e. Truth in space-time.” The one print Waxman has from the photoshoot for this project was commissioned for the exhibition ‘The Left Hand of Darkness’ at the now defunct The Project in midtown Manhattan.² Waxman recalls being thrown out of the printing shop and called a ‘faggot’ by the printer. The exhibition was organized by prescient curators Sarvia Jasso and Yasmin DuBois, now known as the musician LaFawndah. For the coded version for the internet, the photo was cut into a grid which is then animated by a ‘random walk’ javascript.

For exhibition and publication history: http://www.tobaron.com/works/peytach-eynayim/

Amidah: Mincha (central panel of Amidah triptych, performance for large format camera), 2003

Mincha features the central panel of Amidah triptych. The triptych corresponds to the shmoneh esrei prayer, also called the amidah. The three panels allude to the three times the sotto voce prayer is recited: shacharis (morning), mincha (afternoon), maariv (evening). The photos include men in various states of undress, davening and shockeling. There are six figures per photo, realizing a sum of eighteen bodies across the suite of images. Waxman says, “My center of gravity was shifting at this time, the choreography for this performance refigured a center of gravity.”

The photographs were made in artist Barbara DeGenevieve’s studio in Chicago. DeGenevieve was first a friend and then mentor to Waxman. When Waxman came out as trans, SAIC advisors recommended Waxman look to Janice Raymond — the mother of what some now refer to as Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminism, and a virulently transphobic voice in academia from mid 20th century to present day — for guidance in their life-work practice.³ DeGenevieve introduced Waxman to her close friend and collaborator, preeminent trans scholar Susan Stryker. This support and clarity was life-altering, “ We became pen pals!” Waxman laughs. At that time, Waxman was, like many in the year 2000, using a hotmail account.

For exhibition and publication history: http://www.tobaron.com/works/amidah-triptych/

- Artists in Deviant Bodies 2.0 exhibition: Tobaron Waxman (Tel Aviv, IL/Brooklyn, USA), Del LaGrace Volcano (London, UK) Sandy Stone (Austin, TX) Francesca Galliani (Milan, Italy) Linn Underhill (Lisle, NY) Jana Marcus (Santa Cruz, CA) Mirha Soleil-Ross (Montreal, Canada) Emmett Ramstad (Minneapolis, MN) Jay Sennett (Ypsilanti, MI) Jaishri Abichandani (NYC, NY) Tara Mateik (NYC, NY) Michela Ledwidge (London, UK).

- Artists in “The Left Hand of Darkness” included Chloe Dzubilo & T De Long, Tracey Rose, Tara Mateik, Slava Mogutin, Sarah Lucas, Matt Greene, Paul Kopkau, and Ryan Trecartin.

- For those unfamiliar with Janice Raymond, see The Transsexual Empire (1979) and Sandy Stone’s “The Transsexual Empire Strikes Back: A Posttranssexual Manifesto”(1992).