I post a photo to Instagram on erev Rosh Hashanah 5778. The image features Rosemary Mayer’s Balancing (1972), a sculpture that I encountered in person a few months prior. Rayon and cheesecloth fabrics dyed to blushing pinks and golden oranges limply drape between and beneath two overlapping triangles. The triangles, thinly composed of outlined cord, are pinned to a wall at the top corners, while their bottom lines are emboldened and heavied with acrylic rods. The white wall fills in the gaps. The weight of the work feels precarious, in limbo, a see-saw. Two halves, two ribs, a body in indecision. The balance of Mayer’s work is suggestive of scales, appropriate for these days of judgement, yomim noraim.

Looking back at my Orthodox Jewish upbringing, I craved art history because I unknowingly craved divine carnality. At times closeted and celibate, I secretly longed for the ways that Christian artworks could represent and make plastic a divine form in ways that Jewish art would often not. During my early college years, I devotionally researched anthropomorphic visualizations of God in Jewish art, and found almost nothing. Yet later on, coming into queerness, I found that the visibility of portraiture and the solidity of a figure offered artistic forms too constraining for a body that did not feel congruent within the boundaries of normative genders, or even the human. I became interested in the ways that abstraction, suggestion, and gesture could in turn reference myriad personhoods, optics, and histories that escaped representational techniques.

Rosemary Mayer (1943-2014) was a New York-based artist, writer, and critic whose work was prolific and multi-disciplinary. Known for the draped fabric sculptures she made in the early 1970s, Mayer also created artist books, drawings, watercolors, paintings, sculptures, and temporary monuments that generate ideas and sensations around history, temporality, and transience. She was a founder, along with 19 other women, of A.I.R. Gallery in 1972, which still serves as a space to exhibit and support the work of women artists.

Between 1971 and 1973, Mayer predominantly worked on a series of sculptures where she layered and draped an array of dyed fabrics associated with garments and gowns; materials such as nylon, voile, satin, burlap, cheese cloth, netting, and rayon. Voluminous and veiled, these artworks were named after women in history and mythology (i.e. Catherines, Hroswithe, and De Medici), suggestive of the figures to whom they referenced, but abstract in form. They sculpturally reference what garb in historical paintings might look like — delicate, twisting, imposing, sumptuous. Bodies are not figured, but their folds and movements lie in the fabric’s arrangement.

In 1973, Mayer created a fabric work titled Galla Placidia, named after the woman who ruled the Western Roman Empire from 425 to 450. Standing at nine feet, the work’s curved armatures — bent wood forming a hoop shape — support layers of draped gauze and satin that falls downward, skirting the ground. After, in the fall and winter of 1973, Mayer shifted direction with two new works: Bat Kol and Shekinah.¹ Both works are strikingly absent of draped materials. Stripped down to arched wooden bows, tense cord, and tightly wrapped fabric, these relatively minimal yet ornamental sculptures mark a point of transition for Mayer, signaling the end of her draped fabric sculptures.²

After encountering these two works in a publication, I became increasingly curious of how Mayer arrived at such titles.³ Shekinah and Bat Kol are both transliterated from Hebrew and are common references in Jewish traditions to a divine feminine presence. Since Mayer is not Jewish, I wondered where she learned these terms. Was it her training in classics? Her involvement with a feminist cooperative gallery? Was she interested in mysticism?

Most published texts about Mayer’s work and life — both her own writings and others’ — have been out of print for many years. After reading the only two recently published books about Mayer’s works, I reached out to Mayer’s estate, which provided me with incredible support and access to a number of her writings that are no longer in circulation.4 In the 1977 publication Individuals: Post-Movement Art in America, Mayer’s essay “Two Years, March 1973 to January 1975” explains the linguistic origins of Shekinah: “[…] the female manifestation of God, the divine in-dwelling, from Hebrew le-shachain, to reside. ‘The Shekinah rests’ paraphrases ‘God dwells.’ The queen in the Talmud, ‘her splendor 65,000 times brighter than the sun.’” Mayer cites the root of shekhinah in Hebrew, le-shakhain, to dwell or reside. While the term shekhinah does not appear in Tanakh, we find first century texts such as Targum Onkelos and Targum Yonatan interpreting shekhinah as a divine presence. These rabbis understood shekhinah as the “clouds of glory” in the Book of Exodus (40:35) that rest over the mishkan, or tabernacle, whose name arrives from the same root as shekhinah, le-shakhain. Various discussions of shekhinah in Talmud come to bridge the gap between the human and the transcendent, to name an earthly immanence. While occasionally referred to in anthropomorphic terms, shekhinah is not given feminine characteristics or associations in the Talmud, although the word grammatically suggests the feminine. It is not until the medieval period, in kabbalistic texts such as Sefer ha-Bahir and the Zohar, that shekhinah assumes a feminine status as one of the ten sefiroth, or ten aspects of God — often referred to as “bride” of the other nine sefiroth.

Bat kol, a term that literally translates to “daughter of voice,” is presented in rabbinic texts as an echo of the divine voice, intervening in seemingly unresolvable arguments between different rabbis. While this term also does not appear in Tanakh, rabbis in the Talmud assume banotei kol (plural) were present during the Biblical period. The term was understood as the sole form of divine communication between God and human after the cessation of prophecy. How Mayer became familiar with the term is not clear, but, due to its name (“daughter of voice”), it seems reasonable that Mayer understood it as a reference to an aural presence of divine femininity. In “Two Years”, she writes, “For the sense of sight there are angels to pass between God and the world. For hearing there is the word. Bat Kol, the heavenly voice, the female angel of divine pronouncement.”

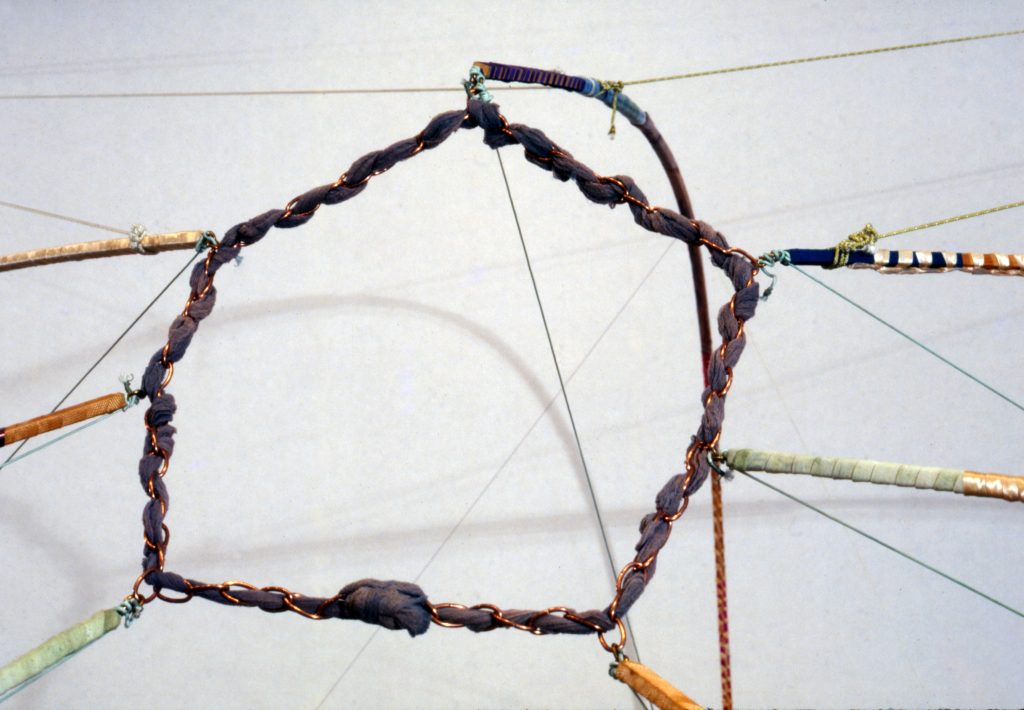

Mayer’s Bat Kol and Shekinah are 7 and 8 feet high respectively, taller than most standing humans, and so require an upward gaze. While Bat Kol is approximately as wide and deep as it is tall, Shekinah rests at 17 feet wide and 12 feet deep, taking up an enormous amount of space. The latter work suggests a tent-like structure, something to be inhabited, relating back to the root le-shakhain, to dwell, and back to the mishkan. Not unlike the mishkan, Mayer’s Shekinah packs up quite small once deconstructed, but in its full installation provides a space for divine dwelling.

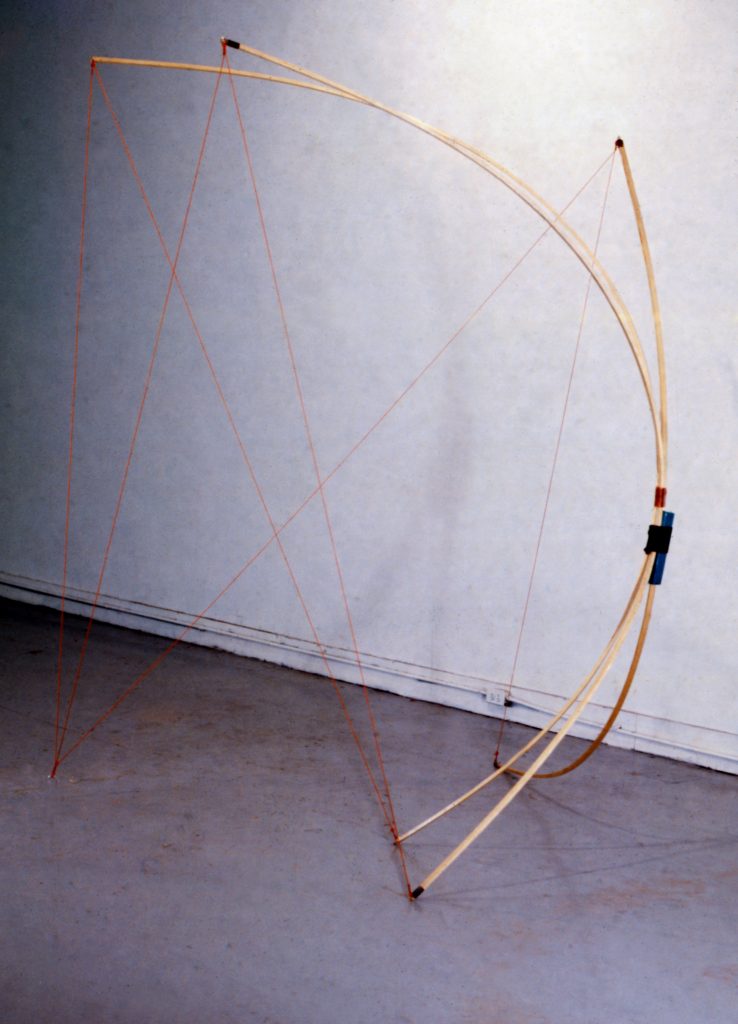

Bat Kol is relatively spare, composed of three arched wooden bows standing upright and tautly held in space with wire and cords the color of vermillion. Mayer warped wooden beams into bow shapes by wrapping them in wet fabric until they curved. Bat Kol’s three bows, whose wood is mostly left bare and exposed, are wrapped together at a center point with green and copper cord. A blue wedge sits at this center point behind all three bows, only visible from certain angles in the photo-reproductions provided. Echoes, sonic reverberations, a voice travelling through space, held in tension, almost harp-like. Indeed, in a later work, The Locrian Mode (1974), Mayer uses the bent wooden structure as a specific reference to musical instruments. These bows are also suggestive of absent quivering arrows, perhaps those of the mythological Diana.

Bat Kol barely stands on the floor, creating something “so delicately balanced it sways from a passing person,” Mayer writes in an unpublished artist statement titled “Passing Thoughts.” In her notes, Mayer writes about her sculptures as “presenting an untenable situation and making it hold….” An ongoing concern of Mayer’s, evident in her writings, sculptures, and temporary monuments, is the evanescent and ephemeral nature of existence. Writing about Shekinah, she emphasizes, “Bows too big, too fragile to be real… the unsuitability of wood to curvature…the limits of breaking, collapse, approached.” Mayer represents the Shekhinah here through the seeming impossibility of material existence, on the verge of breaking. A sculpture that is not real, nor of this world.

While researching these titles, I speculated that Mayer’s derivation of these words resulted from potential relationships with other Jewish feminist thinkers and artists. Several Jewish women artists co-founded A.I.R. alongside Mayer, including Rachel bas-Cohain, Judith Bernstein, and Louise Kramer. Maybe her path crossed with Arlene Agus (co-founder of Ezrat Nashim in 1971, a Jewish women’s study group in New York City) who, in 1976, published an essay on Rosh Chodesh as a women’s holiday, specifically looking at the shekhinah’s relationship to the moon in traditional Jewish literature. The moon was an ongoing interest in Mayer’s sculptures and temporary monuments. Mayer’s notes describe Shekinah’s seven wooden arches as “seven bows, half moons, seven crescents, objects of the queen.”

Through the mid and late 1970s, several rabbis and second-wave Jewish feminists were writing about the shekhinah through a feminist theological lens. There was not a single understanding of shekhinah. Some looked to it as a term and a presence to be mined, while others were critical of shekhinah due to its subservient nature as an emanation of the Divine, as the “bride” of a masculine and patriarchal Yahweh. Some understood it as a metaphor for eventual redemption, seeing shekhinah’s exile as a temporary moment until patriarchy is obliterated.5

Mayer’s Shekinah and Bat Kol draw upon divine descriptions without rendering or representing them via the human body — something that seems recognizably Jewish rather than Christian. However, Shekhinah’s presence in Christian mysticism might have also impacted Mayer’s works. Having grown up Catholic, Mayer mined the aesthetics of her childhood religious settings for her artwork, especially Mannerist paintings and altarpieces. “My family was very religious,” Mayer recalled in a 1976 interview, “church every day and sometimes twice a day […] I suspected that all the variety of textures in the church were affecting my work […] marble, gilding, polished wood, painted ceiling, the statues…” While religious aesthetics played a significant part in Mayer’s sculptures, she warned in her notes that her interest in religious imagery “is not connected to a religion’s dogmas or institutions, but to its sensual manifestations, the swelling, iridescent robes and flowers with which artists have clothed their ideas of deity and dead heroines.”

While Bat Kol consists of three wooden bows, Shekinah contains six symmetrical bows, three on each side, jutting out from a central, circular copper chain wrapped in purple cloth. A seventh bow projects forward from the top center point of the chain. Both Bat Kol and Shekinah are bilaterally symmetrical, which was an intentional choice on Mayer’s part, possibly because these were her first sculptures that did not use the wall for support. Standing on the floor, they might not present an immediately obvious front or back. In the interview, Mayer explains, “The symmetry forces you to look at it from a certain point of view, which becomes the front. One of the things that is most important to me about sculpture is that it comes forward in space.” This forward, frontal projection also insists on an annunciatory reading of both works. In “Two Years,” Mayer published an image of Bat Kol next to a detail image from Matthias Grünewald’s Issenheim Altarpiece (c. 1510), displaying a painting of an Annunciation angel whose draped sleeve unbelievably curves into a half arch. Accompanying these images, Mayer writes, “Pointing at you the way painted angels in Annunciations extend an arm, pointing an imperative […] barely visible, elusive and transparent, their motions caught in folds and layers of floating cloth. Angel sleeves, markers, records of their gestures, their presence.” This bilateral symmetry also suggests that the arched bows on each side of the center are angel wings; in the case of Bat Kol, two wings, or in Shekinah, six wings, possibly those of Seraphim (see Isaiah 6:2).

Despite the impact of Christian aesthetics on Mayer’s artworks, Shekinah and Bat Kol serve as a rejection of the anthropomorphic, in ways that continue, and break, from her previous sculptures. As opposed to the draped fabric sculptures that were named for specific women, Mayer’s Shekinah and Bat Kol resemble not as much a particular goddess or deity but a numinous or sonic presence, an energy of the divine. In 1977, Mayer wrote on a silver gelatin print featuring a reproduction of Bat Kol that these two works “were titled […] to suggest, not ‘goddess,’ which implies a sharing in, similarity to, humanity in form or psychology, but, in the case of the Shekinah, possible female aspects of the invisible presence of deity, or universal female energies, and, in the case of Bat Kol, an immaterial female angel whose only presence is sound.” Mayer’s Shekinah can be seen as angelic, a messenger, affiliated with a Kabbalistic notion of the shekhinah as an emanation of the divine godhead.

In “Two Years,” Mayer describes Shekinah as “the invisible presence, among the colors, the arches bows, the chain to catch her.” The form of Shekinah creates an invisible presence through its spare and skeletal armature. It appears less as a representation of Shekhinah and more as a space in which the Shekhinah can be caught or reside. The draped garments that clothe a figure are now absent because the figure itself is absent. Instead, the bows of Shekinah are tightly wrapped in fabric, string, and ribbon in various colors. “Different hues,” Mayer continues, “[of] the greens, lavenders, oranges of Galla Placidia, wrapped […] on the bows of Shekinah, but absent from Bat Kol.” Mayer created Shekinah as a formal and material transformation of earlier draped sculptures such as Galla Placidia by exposing its wooden supports and extending its color palette.

The transparent, diaphanous nature of both Shekinah and Bat Kol suggests a looking through at what is present, but not visible. In other words, the visible makes present what is invisible. In her 1973 notebook, Mayer jotted down a quote from A.E. Waite’s The Holy Kabbalah (1929), the only known secondary source informing her understanding of shekhinah: “Alternatively, it was a cloud that rose up to veil her [shekhinah’s] presence, and dissolved when she went forth.” Interestingly, also in 1973, Mayer wrote an unpublished article about Morris Louis’s Veil paintings, where he would pour and stain overlapping translucent paint colors, not unrelated to a series of Veil sculptures Mayer created between 1971 and 1972. In her article, Mayer understands material and formal transparency in both painting and sculpture as something “that brings to mind creatures and appearances from other realities or things not normally visible.” She relates this back to religious paintings, invoking Grünewald yet again: “While Grünewald’s work is obviously religious because of its subject matter, the Veils are religious in a universal sense.” Translucence and transparency allow for visualizations otherwise unavailable. The veils of fabrics from earlier sculptures have been lifted in these two works — their transparencies lie in the empty spaces between scaffolding and barely-there cords.

At the corner of the photographic print of Bat Kol mentioned above, Mayer wrote the words, “Beware of all definitions.” The indefinable is a useful way to view and think about Mayer’s works, especially Shekinah and Bat Kol whose references to, and forms of, divinity are multivalent, transparent, and immaterial. Their genders are suggestive rather than sexed, created during a time when many feminist artists were creating work that more explicitly imaged goddesses and women’s bodies. Mayer built her sculptures in ways that do not allow their forms to be fixed, even when they relate to a unique source of inspiration or reference. Similarly, we might think of the terms shekhinah and bat kol as indefinable according to their dual categories of divine and feminine, as not conforming to a single representation or understanding. Mayer’s sculptures suggest that divinity and femininity are not simply found in what we see, but what we might hear or feel. What might be recognized only in the absence of forms — presences created between forms, but not of them.

- I will be using two spellings of this word throughout: Shekinah to refer to Mayer’s sculpture, and shekhinah to refer to the notion more generally.

- Though, one could argue Mayer synthesizes a different combination of folded materials with more exposed wooden structures in later works such as Ista and Portae.

- Bat Kol as an original sculpture no longer exists. Shekinah remains, yet it has not been installed or exhibited since 1978.

- For books currently in print on Mayer’s works, see Warsh, Marie (ed.) Temporary Monuments: Works by Rosemary Mayer, 1977-1982. Chicago, Soberscove Press. And Warsh, Marie (ed.) Excerpts from the 1971 Journal of Rosemary Mayer. Chicago, Soberscove Press.

- See Luke Devine, “How Shekhinah Became the God(dess) of Jewish Feminism”, pp. 78-83.