This essay is a revised version of a talk given by the author as part of the exhibition DI FARBLOYTE FEDER | BERLINER ZEYDES, by Ella Ponizovsky Bergelson and Arndt Beck, in August 2019. The festival was accompanied by a series of lectures, concerts, films (curated by Arndt Beck and Ekaterina Kuznetsova) and was the first appearance of YIDDISH BERLIN. A second edition followed in January 2020 (LEKOVED AVROM SUTZKEVER). To be continued…

Wait… Anshl? Who is Anshl?

At first, that name might not ring a bell. Not unless we remember that Anshl is the main character of Yitskhok Bashevis Singer’s famous short story “Yentl the Yeshiva Boy,” later made into an even more famous film starring Barbra Streisand. Then still: Wasn’t Yentl the main character of this story? Yentl, the girl, who joined a yeshiva, disguised as a man, so she could study Torah?

By turning focus to Anshl, I do not wish to marginalize Yentl in Bashevis Singer’s story. Interpreting the main character as a woman has been a crucial practice for feminist readings of the material. From such a perspective, Yentl’s move into the traditionally male-connotated space of Torah study is a powerful claim for equality in terms of access to religious knowledge and ritual.¹ But as with any fictional text, an interpretation is shaped by the one interpreting. Different people approach the text differently, see different details, make different connections. In the case of Singer’s story, the text’s various interpretive possibilities depend on the version of the story one engages: I had always enjoyed reading “Yentl,” but it was not until the Yiddish version fell into my hands that it struck me that there is another story in there: one in which the hero is a trans character.

When I gave a talk about Singer’s story in Berlin in 2019, the room was filled with both familiar and unknown faces. A good percentage of the people in the audience identified as queer, trans, or non-binary. The talk was part of a series of events organized by Yiddish Berlin, a group of Berlin-based Yiddishists and artists, under the name “Berliner zeydes,” or “Berlin grandfathers.” Preparing my talk, I had thought about how to make the “zeyde” theme a part of my presentation. I decided to speak about trans kinship and to recognize the main character of Singer’s story as a figure of trans identification, as a trans elder — “Anshl, undzer zeyde.” But it was only after the talk, when various people approached me to share how important “Yentl” had been for them at different moments in their lives, that I felt Anshl did indeed hold the status of a trans zeyde of sorts, and not only for myself. I especially remember one person, visiting from abroad, who had heard about my presentation only at the last minute. “I really needed to come!” they blurted out excitedly. “This has always been such an important text for me. I felt so seen reading it when I grew up being trans in the 1970s. There were not many points of reference for me back then.”

What is it that draws trans people to this story?

The plot of the 1983 film — directed by, co-written by, and starring Barbra Streisand — follows Yentl, who had studied the Torah with her father in secret, as she runs away from her shtetl, disguised as a boy, in order to pursue her dream of studying in a yeshiva. The rest of the story is well known: Yentl meets a charming and slightly mysterious man named Avigdor at an inn and she decides to join his yeshiva. She falls in love with him, but since she presents as a boy she cannot succumb to her feelings. In order to stay close to Avigdor, Yentl agrees to marry Avigdor’s impossible love interest, Hadass. Of course, the marriage between disguised-as-a-boy Yentl and Hadass comes with some obstacles, culminating in Yentl quite awkwardly avoiding touching her bride on the wedding night. Eventually, the relationship gets too messy and Yentl can no longer lie about her “true” identity. She tells Avigdor that she is in fact a woman and decides to leave behind the world in which she had grown up. At the end, she is en route to the United States, standing at the rail of a ship crossing the ocean, and singing on the top of her lungs an emphatic song about her newly gained freedom.

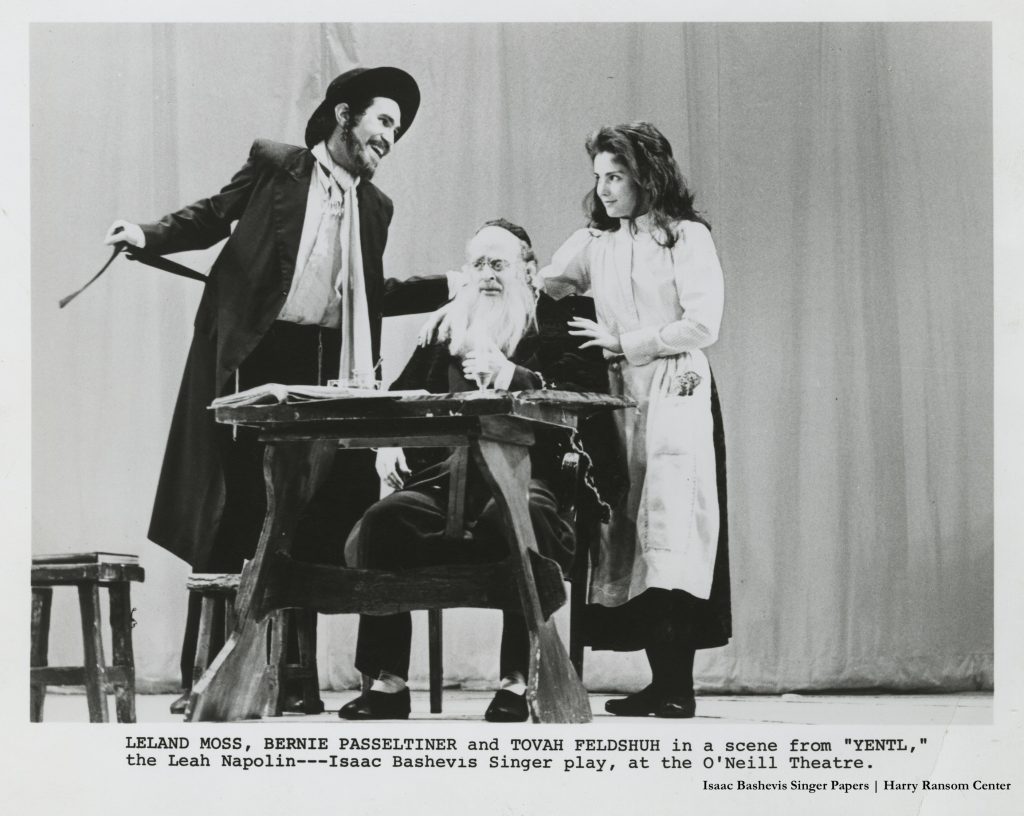

There is, however, no one single version of this story — even if the one I just summarized is the most dominant version in US-American (and certainly also Western European) consciousness. In fact, there are not only several versions of the written short story (a Yiddish and an English version) but also another screenplay (based on the short story and written by Leah Napolin and Bashevis Singer), which then served as the basis for new versions such as Shirley Serotsky’s 2016 play “Yentl,” set to original music by Jill Sobule. Because of the iconic status Streisand’s “Yentl” holds today, many who have only seen the film believe they are familiar with Bashevis Singer’s story. But those who have read an English version of the Singer short story will notice that Streisand’s interpretation does not fully coincide with the source material, as even Singer himself criticized. At the end of his version, for instance, Yentl does not leave for the United States but remains in Eastern Europe, looking for a new yeshiva. As Bashevis Singer asked, “Was going to America Miss Streisand’s idea of a happy ending for Yentl? What would Yentl have done in America? Worked in a sweatshop 12 hours a day where there is no time for learning?”

“Was going to America Miss Streisand’s idea of a happy ending for Yentl? What would Yentl have done in America? Worked in a sweatshop 12 hours a day where there is no time for learning?”

Also, as others have noted before, the Streisand film seems to follow a different agenda than Bashevis Singer’s story, emphasizing the fact that Yentl is a woman by reminding us throughout that the character is “in disguise.” Look, this is not really a man, the movie reminds us, but Streisand, with a somewhat weirdly-parted and short haircut, round metal-framed glasses, a funny puffed-up cap, and a stiff black coat! Consequently, the wedding scene between the two women radiates a palpable sense of lesbian panic.²

Reading ”Yentl” as the story of Anshl, the (trans) yeshive bokher, leads us to the Yiddish version of the story. Bashevis Singer wrote the Yiddish version first, even though it was only published in 1963 in the literary journal Di goldene keyt — that is, a year after the English version appeared in Commentary magazine. The English version was the more widely read one: in the US of the 1960s, the Yiddish-speaking population had already declined so drastically that for most readers that story was only accessible in English. Those, however, who do know Yiddish and have undertaken the endeavour to read the English and Yiddish version side-by-side have noticed the changes between the two versions — changes that are not at all insignificant.³ One of the biggest differences between the two is the use of pronouns. While the English-language Commentary magazine version employs female pronouns for the main character, even when using the name Anshl and not Yentl, the Yiddish text overwhelmingly employs male pronouns.

This pronoun distinction makes a considerable difference for how we understand the texts. In the Yiddish, the story does not end with Yentl, the girl in disguise. It is Anshl who sets out on a new journey, looking for a yeshiva, in masculine clothing and referred to not only with a male name but also male pronouns.

Things get interesting at this point. If the text emphasizes the maleness of the character who was, as we say today, assigned female at birth, can we then speak of Anshl as a trans character? Of course, one could argue that this kind of approach risks an anachronistic appropriation of the material. Such claims would overlook, however, that transness was nothing unknown in the time of Bashevis Singer (a fact I will return to later). Even more significant, trans-identifying people themselves are often fascinated by the protagonist of the story, frequently recognizing the character as “one of us” — as was the case with my personal experience and exchange in Berlin.

But what is it exactly that makes such a powerful identification available?

Let’s go back to the beginning of the story, this time in Yiddish. One of the first things we learn about Yentl (as the character is referred to at this point) is that Yentl is different from the women of the shtetl Yanev:

“Yentl hot gevust az zi toyg nisht tsu vayberishe sakhn. Nisht zi kon neyen, nisht shtrikn. Di gekekhtser brent zi on, di milkh loyft oys, dos tsholnt gerot nisht, die khale yoyrt nisht. Der kopf iz ir farnumen mit mansbilshe inyonim. In di yorn vos der tate Reb Todres boyrer iz gelegn geleymt, hot er mit ir, der tokhter, gelernt vi mit a zun.”

“Yentl knew she wasn’t cut out for a woman’s life. She couldn’t sew, she couldn’t knit. She let the food burn and the milk boil over; her Sabbath pudding never turned out right, and her challah dough didn’t rise. Yentl much preferred men’s activities to women’s. Her father Reb Todros, may he rest in peace, during many bedridden years had studied Torah with his daughter as if she were a son.”

Yentl, as this scene tells us, isn’t able to properly perform activities and duties that are linked to femaleness in the surrounding social world: Yentl cannot sew, cook, or knit. Instead, Yentl’s head is filled with “men’s stuff” — and this means, first and foremost, the study of toyreh.

One could easily argue that the whole plot is concerned with gender in the sense of a gendered social role. In this light, the tragedy of the story would arise from the female protagonist’s interest in activities coded as male and therefore forbidden to her. While I think this approach is well-supported by the text, we can extend beyond this claim by asking two questions: First, how does gender operate within the context of this story in a way that goes further than a mere equation of gender identity and gender role? Second, if we read closely, does the claim that the character’s only longing is to study toyreh still hold? Or is it possible that there is something even more urgent that drives the character?

A good point of departure for thinking about how gender operates in the story is found in another noteworthy exchange between father and child, before the father’s death. . The text reveals:

“zi hot bald bakumen bay im aza peule az er hot getaynet:

– Yentl, du host a neshome fun a mansbil.

– far vos zhe bin ikh a nekeyve?

– in himl makht men oykh teusim.”

“She had proved so apt a pupil that her father used to say:

‘Yentl — you have the soul of a man.’

‘So why was I born a woman?’

‘Even Heaven makes mistakes.’”

Once more, one could argue here that Yentl’s otherness stems from the character’s ability to successfully perform activities traditionally associated with masculinity. Following this reading, Yentl has “proven” masculinity by being especially gifted in studying Jewish scripture. But we could also ask how “being a man” may be expressed in the world of the protagonists if not by linking it to a certain gendered performance. This becomes clear when we understand maleness as well as femaleness as categories first and foremost constituted in the realm of traditional, rabbinic Judaism as practices: men are obligated to perform certain acts linked to the 613 mitzvot of the Jewish law while women are exempted from time-bound, positive commandments. So, how does one identify a man in a Polish shtetl if not by his garment — the character will indeed soon present in male clothing — and what he does?

How does one identify a man in a Polish shtetl if not by his garment — the character will indeed soon present in male clothing — and what he does?

It is important to keep in mind that a preference for the typical activities and attributes of the gender category with which one identifies can serve as a means to describe a deeply felt sense of belonging. Today, more often, we shift away from this all-too-easy conflation of gender role and gender identity. But we should consider how transness would have been narrated and understood in the United States in the 1960s, when Bashevis Singer’s short story emerged. The public conception of transness at this time was shaped by the case of Christine Jorgensen, who had undergone sex reassignment surgery in 1952 and became a figure of public interest. In 1966, sexologist Harry Benjamin’s The Transexual Phenomen was published and perpetuated an idea of transness (today often criticized) as a soul trapped in the wrong body. Both cases reflect the possibilities and limitations of expressing transness in the US at a time when visibility, access to resources, and basic rights were closely linked to a highly stereotyped narration of gender and a conception of transness as a soul-body incongruence.

The idea of having the body of one gender and the soul of another gender, however, is not necessarily reducible to 20th century sexology. Returning to the setting of the story, the world of 19th century Poland, we should ask how transness could have been expressed in this context — apart from questions of gendered social roles. Against this background, we can return to the conversation between Reb Todres and his child once more.

The father suggests that Yentl “has the soul of a man.” In fact, he is saying that Yentl not only acts as a man, but that there is something manly in Yentl that exceeds visible practice. To understand the implications of this reading, we may turn to the rabbinic textual tradition — the world not only of Reb Todres and Anshl, but also of Bashevis Singer, who grew up the son of a Hasidic rabbi in Poland. Within this textual culture, especially its mystical dimension, the idea of soul wandering — gilgul — and the possibility of soul switching are not unusual.4 It is not an overstep to translate this concept of gilgul into today’s understanding of transness, as a deep felt sense of identification with a certain gender, as something that cannot be seen immediately from the outside but is part of one’s innermost feelings and sensations, forging one’s self-perception.

Yet, there is also a visible element of gender in “Yentl.” In addition to gender performance and the idea of a gendered soul, the text reveals physical markers of the character’s otherness:

“zi, Yentl, iz geven andersh fun ale shtotishe meydlekh:

hoykh, dar, beynik, mit kleyne bristn un shmole hiftn.

shabes bay tog ven der tate iz geshlofn hot Yentl ongeton zayne hoyzn, dem zaydenem ibertsier, dem tales-kotn, dos sametene hitl mitn kapl, zikh avekgeshtelt baym shpigl, batrakht ir opbild.

zi hot oysgekukt vi a shvartskheynevdiker bokher.

s’iz ir afile gevaksn a pukh iber der eybershter lip.

bloyz di tsep hobn eydes gezogt az zi iz a vaybsparshoyn.

nu, ober tsep kon men opshern.

in Yentls moyekh hot zikh gevebt a plan.”

“There was no doubt about it, Yentl was unlike any of the girls in Yanev — tall, thin, bony, with small breasts and narrow hips. On Sabbath afternoons, when her father slept, she would dress up in his trousers, his fringed garment, his silk coat, his skullcap, his velvet hat, and study her reflection in the mirror. She looked like a dark, handsome young man. There was even a slight down on her upper lip. Only her thick braids showed her womanhood — and if it came to that, hair could always be shorn. Yentl conceived a plan and day and night she could think of nothing else.”

In short, it is only the long braids that make Yentl a woman — and these can be shorn off. And, not only that, but we also learn that Yentl starts wearing masculine clothing even before it becomes a means to escape the world of Yanev and enter a yeshiva. It is hence much more than a disguise that the character strategically uses to pursue the dream of study, as Streisand’s movie had it. In this context, wearing the clothing one chooses for oneself is not a masquerade or a play but an act of literally putting on a skin that fits. In trans narratives and biographies, putting on the garments of a/the preferred gender, which in repressive social situations must happen in secret, is a common trope.

Besides the character’s preferred clothing, we learn about Anshl’s physicality. In the description of the character’s body, the six genders of the Mishna resound. It becomes clear that, from a visual perspective, Yentl is not easily classified as either male or female. The character’s gender could be linked to the androginus (that is, a person who has both “male” and “female” sexual characteristics), tumtum (a person whose sexual characteristics are indeterminate or obscured), or aylonit (a person who is identified as “female” at birth but later develops “male” characteristics).5 Ultimately, none of these categories fully fits the character, but the described physical complexity clearly alludes to the multiple genders elaborated in rabbinic text. One of the strengths of Bashevis Singer’s original text is that it explicitly roots the character’s gendered otherness in the contextual setting of the story: the complexity of Anshl is only legible in the context of Jewish (textual) culture.

If we follow the Streisand movie (and most of the reception of Bashevis Singer’s story), it is the character’s desire to study in a yeshiva that leads to the transgression of presenting as a man. Indeed, the study of Torah is very central to the plot. But does the sheer love of engaging in scholarly inquiry and dispute really explain what makes Anshl, Anshl? At the end of the story, when Anshl has revealed his secret to Avigder (as the name of Avigdor is pronounced in Yiddish) and Avigder has overcome his first shock, he begs Anshl to stay. Trying to find a way to go on, Avigder proposes that they marry and live together. But this is not acceptable for Anshl:

“– vos meynstu?… neyn Avigder, s’toyg nisht.

– far vos nisht?

– ikh’l shoyn iberkumen di yorn azoy…”

“‘No, Avigdor, it’s impossible.’

‘Why?’

‘I’ll live out my time as I am. . .’”

The text is explicit: in order to remain himself, Anshl must leave. Staying would mean remaining married to Hodes (Hadass) or getting divorced and marrying Avigder. The first option has fallen through as Anshl fears that he can’t hide his female- (or ambiguously-) interpreted body any more from the community of Bechev. People have begun to notice that he never attends the shvitz, the communal steam bath, on Friday, and Hodes has not become pregnant for a suspiciously long time after their marriage (note also that the lack of pregnancy is a very common trope in trans narration). And being with Avigder would mean to marry him as a woman — something that Anshl clearly rejects: “ikh’l shoyn iberkumen di yorn azoy…”

It is here, at the end of the story, that we hear Anshel explicitly talking about himself. Anshl insists on being “azoy,” or “as I am.”

Avigder keeps insisting, trying to convince Anshl that Anshl doesn’t have to fill the role of a gut vayb, a good woman, within this marriage, implying they can continue studying Torah together. Anshl responds: Neyn, Avigder. s’iz nisht bashert. It is not meant to be. There is no doubt: Anshl does not see Avigder’s offer as a liveable option, for it would require him to deny his sense of self.

Anshl’s refusal becomes even clearer when Avigder asks Anshl if there is any possibility that Anshl presents as a woman again. When Anshl negates, Avigder adds in amazement:

“farlirn oylem-habe iz beser?

efsher…”

“‘Would you rather lose your share in the world to come?’

‘Perhaps. . .’”

Anshl is willing to lose oylem-habe, eternal life, in order to live truthfully on earth. This pulsing intensity feels so familiar to those of us who also had to create our own path. We know that the anxiety of losing certainty and, often enough, losing people is inextricably intertwined with the empowerment that comes from exercising agency. Because of these high stakes, the text serves as a point of reference for Jewish and non-Jewish trans and queer people alike. It is a story about taking the risk of losing, but at the same time it tells us about the strength of those not willing to let go of the world — and the toyreh — they hold dear.

- See, for example, Helene Meyer’s take on the Yentl story (in this case, primarily the film).

- On the ‘heterosexualization’ of the Yentl material in the 1983 film, see Warren Hoffmann, The Passing Game. Queering Jewish American Culture. New York: Syracuse University Press 2009, p. 124f.

- Anita Norich has written extensively about the issue of translation in Bashevis, see, for example Norich, Anita. “Isaac Bashevis Singer in America: the translation problem.” Judaism: A Quarterly Journal of Jewish Life and Thought 44, no. 2 (1995): 208-218.

- Abby Stein has provided a very insightful summary of the idea of soul wandering in Kabbalah and Hasidus.

- See Mishna Bikkurim 4.