FEAST: Semipermeable Membrane is a dinner performance conceived and staged by Ana Ratner with a plant-based menu by Lily Consuelo Saporta Tagiuri. The below text was written by Tagiuri to accompany the performance on January 7, 2020, at Repair the World Brooklyn. The event was curated by Aimee Rubensteen.

I didn’t know how miraculous it was that my mother wrapped dolmas using baby grape leaves from the vine behind our home, or how improbable it was that the eggplant with tomato or stuffed peppers made their way to my plate. We always ate festively with evil eyes watching from her necklace, the wall, my bracelet. I didn’t know the percentages of our luck, or the ways these recipes traveled. A recipe is a way of time traveling, of enacting the same choreography that someone decades or miles away has followed before. For a recipe to survive, it must be archived; but for it to live and be known, it must be cooked and shared. It is only recently that I have started to revive some of these recipes and tried to understand them.

These dishes started with peace. In the south of the Iberian peninsula, Muslims and Sephardic Jews blurred the boundaries between their neighborhoods, foods, and languages. After decades of sharing land and cultural experiences, the Catholic Reconquista violently exiled the Sephardis and Muslims from what would then become Spain. Scattered and fractured, only 20% of the Sephardic Jews survived. However, their cuisine spread to new lands in which they settled. My family landed in Salonica, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire and is now Thessaloniki, Greece. Much of what grew in Spain also grew there—eggplants, artichokes, tomatoes, peppers, olives, all touched by the salty Mediterranean air. In a community of Sephardis who spoke Ladino — a disappearing form of Spanish — they cooked. I have heard that even when money was scarce, they still made elaborate meals of layered dough, stuffed vegetables, rice scented with citrus or rosewater — two aromas that were also the perfumes of my mother and grandmother.

Only in the past year have I learned new details about this history from my mother. My great-grandfather contracted rheumatoid arthritis when he was a teenager, leaving him hunched over and needing canes to walk. He became a historian, a steward of Sephardic culture, and wrote in 13 different languages. It was not until the tail-end of the war that my grandmother and her family were sent to the camp. My great-grandfather together with my grandmother took it upon themselves to educate the youth trapped there. He took meticulous notes about this experience, writing on scarce paper in a font illegible without a magnifying glass. These notes included math equations, anecdotes, and recipes. As a scholar, he knew the value of an archive and recognized in this moment of near-death that recipes would otherwise be lost. In another stroke of luck, my grandmother’s family survived largely due to the fact that they held Spanish passports; 97% of their community did not.

This loss was never discussed with me outright. It was alluded to, but I was young when my mother’s parents passed away and I never heard a first-hand account. I wasn’t raised to consider myself Jewish. I knew my grandmother often wore emerald green but I didn’t know the first sweater she had when she was released was that deep and vivid color. I knew my grandmother would stay in bed until noon, smoke from her cigarettes sneaking under her door, but I didn’t know the pain that kept her stuck to the bed like a weight and that emerging from it took every ounce of will she had left. I knew my mother resented the Thanksgiving when my grandfather jumped in the water with his spearfishing gun and caught an octopus for lunch, but I didn’t know how much we were a part of the water until my mother upon seeing the Mediterranean Sea ran in with all her clothes, splashing in the waves, like she was reuniting with an old friend. I knew my mother mourned her parents, that we lit candles for them, but I didn’t know it was because of them that my mother ate artichokes almost every night of my childhood, or that one summer when she made hundreds of dolmas, until the grape vine thinned into fall and I began to hate them, that she was communicating with her family.

—

Nine Steps to Sephardic Cuisine

Start with a peaceful exchange.

Get exiled.

Survive.

Plant the foods you left behind. When ready, harvest, thrive, and share for 500 summers.

Protect yourself, protect the knowledge, and you will protect the community. Protect others, protect their stories, and you will protect the future.

Survive.

Resettle as many times as you need to feel safe and like you have a home where you can cook the food of your childhood. Preferably near the ocean or sea so you can fish.

Obscure. Don’t say too much or they will be scared. Don’t share too much until they are ready to hear, and when they are ready to hear, serve them.

They will try to understand. They will try to know. They will serve others.

Lily Consuelo Saporta Tagiuri

—

The Semipermeable Membrane.

The mouth is our gateway between an external and internal world, and the tongue acts as its gatekeeper—tasting and letting through what will become a part of us. In a similar way, traditions, myths, and traumas filter through generations. We taste, and sometimes swallow, the inheritances of our family, choosing whether and how to ingest what we’ve been given.

On both sides of my family, women were hosts. Days were spent not only creating meals—shopping, cooking, and serving—but also preparing to play the role of a perfect host. Hosting at meals, and playing host to the emotions and needs of others, are traits I’ve inherited.

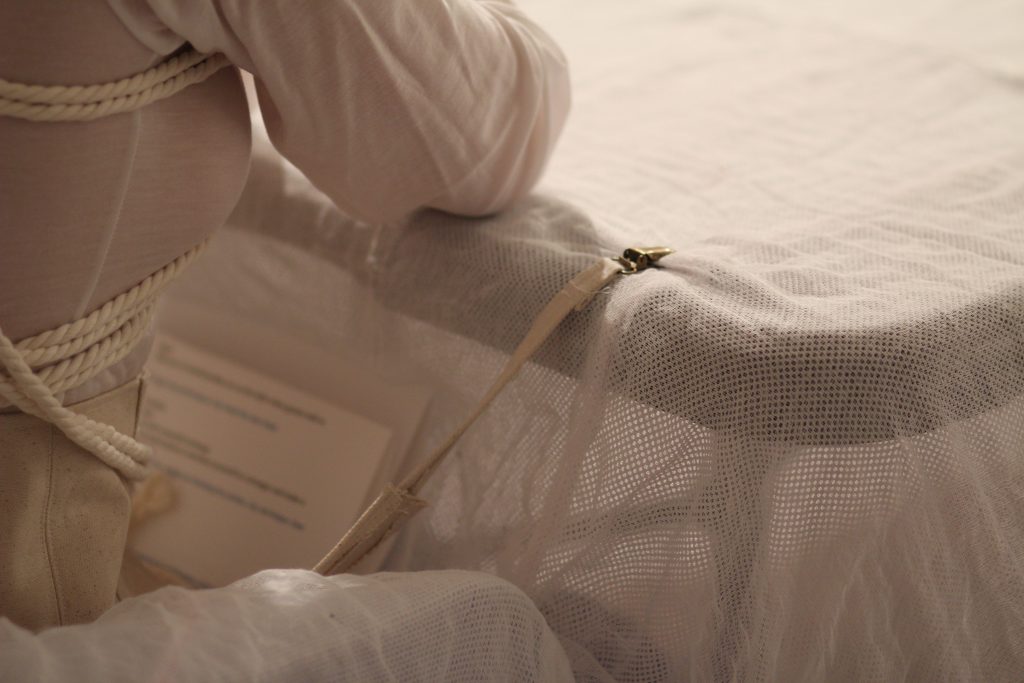

By performing FEAST, I work to understand the experience of being bound—by my ancestors, to their dynamics and traditions. I think of what it meant for my ancestors to play host, how I interpret that role in my life, and what I’ll share with the next generation. Especially when exploring the legacy of the host, self-interpretation and awareness is key, lest we become vulnerable to the anti-host, the parasite. When we open ourselves, our mouths or our tables, to others, we risk letting in unwanted guests of all forms. My hope is for each of us to be like a semipermeable membrane, able to discern and choose which guests we carry with us and which we leave behind.

Ana Ratner

—