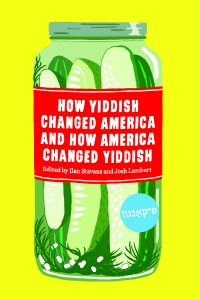

The following story is excerpted from How Yiddish Changed America and How America Changed Yiddish (2020), edited by Ilan Stavans and Josh Lambert.

Translated by Bernard Levinson.

—

Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Interrogation Dossier #79436-AF12

Name: Ina Betancourt Palacio

Place and Date of Birth: Bogotá, December 25, 1961

Citizenship: Colombian and French.

Partial account recorded on July 15, 2008 with emphasis to FARC terrorist Jardiel Poncela:*

My name is Ina Betancourt Palacio. In total, I was in bondage for over six years: I was kidnapped on February 18, 2002; my release took place on July 2, 2008. In response to your question, yes, I speak Yiddish to my son Jorge Tata Poncela Betancourt.

Though I don’t say it in public because I feel regretful, I come from the Colombian upper class. My mother was gorgeous; this explains why she was a beauty queen. But the family wasn’t into distractions; it was involved in politics. My father was Foreign Minister and my mother, a congresswoman who worked in shelters. When Luis Carlos Galán, the candidate for Colombia’s president, was assassinated in 1989, she was right behind him.

Since I was little, I was involved in environmental issues. Unlike my mother, I knew the biggest challenge facing Colombia was the decimation of its natural resources. I studied political science at the Sorbonne. In 1983, I married a French citizen, Fabrice Debayle. We lived in Paris for years. Our two children, Laurent and Margaret, were born there. Debayle and I divorced in 1994, which is when I returned to Colombia. For a while, I worked for the Ministry of Finance.

I was a senator and anti-corruption activist before I ran as a presidential candidate in 2002 with the Partido Verde Oxígeno, also known as Green. My autobiography appeared the year prior. It is called Las turbulencias del corazón (in English, Green Is the Color of Hope [2004]).

I was scheduled to visit the demilitarized zone in a campaign stint. There were a number of road blocks. My campaign manager suggested I take a helicopter. I agreed but there were rumors the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) had taken over the airport from where copters took off and landed. I chose to go on a van from Florencia to San Vicente del Caguán. I was kidnapped about one hour into the trip.

The FARC blindfolded me, my driver, and two other people in the van. They put us in a school bus. We drove for many hours. I know we arrived in the jungle because of the humidity. I don’t know the exact location.

I was put in an empty room alone. When the blindfold was taken off, I realized it was an abandoned school classroom. It must have been in the demilitarized zone. I stayed there for several weeks. They later transported me to several other undisclosed locations, always in the jungle.…

My captors didn’t communicate with me their demands. I didn’t even know if they were in touch with the authorities or with my family. I was treated humanely, though. They fed me at regular hours: breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Once a week, I was able to shower in the bathroom of a private home.

The wave of so-called “express kidnappings” made me believe I would be ransomed soon. Of course, I was also a prominent political figure, which to me meant all arrangements for my freedom would need to take place either secretly with the police or out in the open, with the media fully involved. I preferred the former but I didn’t have a choice.

I later found out the government tried to rescue me in 2003. The French Government — I have a French passport — was involved in the endeavor. I didn’t know anything at the time. But that’s about when the FARC forced me to make a video in which I called for the government to surrender and the FARC to assume power. Although I myself was aware of how elusive these demands were, I faked it. I had learned how to fake while working in the Ministry of Finance.

It took a bit for me to realize my high profile had complicated any possibility of dialogue … Andrés Pastrana was president when I was taken away. When Álvaro Uribe was elected, his right-wing policies complicated his dialogue with FARC.

It might have been a year after the kidnapping, maybe sixteen months, when I met Jardiel Poncela. I don’t know if he was Yukpa, Bora, or Witoto. He spoke an indigenous language. At least at the beginning.

He was around twenty-five years of age. Handsome, oily hair, in aboriginal clothes. Always well-kept. He had a rifle at his side whenever he was in charge of guarding me. I assume his orders were to make sure I didn’t escape. I wouldn’t have been able to. I didn’t know my way through the jungle. And I was friends with Iñaki (I don’t remember his last name), the Vasque photographer. He was brought to the location where I was kept during my second year in bondage.

It wasn’t uncommon to talk to our captors; I not only communicated with Jardiel but with several others, Raquel Timaña among them.

Unlike the emotions I experienced with several other captors, I was never intimidated by Jardiel. On the contrary, our exchanges were always friendly, even jovial. Since the beginning, he was cordial — to a fault. He would want to make my stay pleasant, as if he didn’t agree with the FARC ideology. But he was a soldier through and through. He would sometimes describe, in frightening detail, military operations he participated in. Or call them terrorist acts: he and his squadron invaded villages looking to recruit young men. He said that when they left the place, there would be several corpses left behind on the sidewalk. “Blood shines when it spills.”

I was struck by his writing, too. Every third night, as he was on guard outside my room, he would write in his diary. I asked him about it. He said his involvement with the FARC had changed his life. He understood why Colombia needed change. He said he wasn’t a Green, like me, but he loved the forest. It was full of spirits. Rivers, every tree, every stone had its own character, its voice. In the middle of the night, if you were quiet you could hear them converse. The amount of wisdom you would acquire would be invaluable. This was especially true during storms because all elements in the jungle become aroused then. “The resin of trees is like semen,” he said.

Jardiel’s handwriting was indecipherable to me. I assumed he had learned those letters among his tribesmen.

One day, after Jardiel served me breakfast — this wasn’t unusual, since my health was a concern to my captors — he started talking in a way I didn’t understand. Not that the topics were secret. He had been given orders not to disclose any sensitive information with me. What made the conversation intriguing was that his words sounded like those of a friend I had in childhood, Estersita Rabinovich. Not her per se but her parents and especially her abuelo.

What made the conversation intriguing was that his words sounded like those of a friend I had in childhood, Estersita Rabinovich. Not her per se but her parents and especially her abuelo.

I asked Jardiel what he was saying. I needed help.

“It’s in Yiddish!”

I was surprised.

“You speak that language? How did you learn it?”

“We don’t speak it among the Quayuubu. It was never spoken by our ancestors. Great Master Quimbaya made his announcements in Quayuubusé.”

He paused. Then he told me about Tata Grabinsky.

“He came to visit us one evening. He was old. He said he had a message for us. Most of the tribe ignored him. But I got to talk to him and became his friend. Tata Grabinsky said it was time to resist the colonizers. Colombia was at a crossroads. The aristocrats were taking everything for themselves. The people needed to reclaim what was theirs. He said he had been a businessman in Bogotá but had given up everything to come to the jungle and join the struggle.… He spoke to me in Yiddish. I didn’t understand anything at first.”

In 2006, the French government made a proposal to the FARC for the exchange of prisoners, including me. Foreign Minister Philippe Douste-Blazy stated that it was “up to the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia to show they were serious about releasing former Colombian presidential candidate Ina Betancourt and other detainees.”

I was occasionally allowed to listen to radio or watch TV in a restaurant less than a kilometer from where I was kept imprisoned. Those images sometimes made me think of my candidacy. I’m not sure I still want to be president of Colombia.

At any rate, by then my relationship with Jardiel had matured. He had figured out ways to be assigned to me. On a regular day, we would spend five or six hours together. Naturally, we fell in love.

I taught him how to speak French and he taught me Yiddish. He said he and his FARC colleagues weren’t terrorists, even though the Colombian government frequently portrayed them that way.

He described how Tata Grabinsky — I believe he was from Uruguay, or perhaps Chile — had been a rabbi. He was involved in arms sales in various countries, including to the Nicaraguan Contras. Jardiel said Tata Grabinsky didn’t see any conflict between war and faith. He would pray three times a day. Jardiel said he had never seen a Jew recite liturgy in his life before. He also said that Tata Grabinsky was involved in helping Jews in Bogotá, Caracas, and other cities organize as an army in case the governments of those countries didn’t help when there was an anti-Jewish attack.

In July 2007, I saw my daughter Margaret on TV. I became sentimental when I saw her. She was in a press conference in which she announced that the French Embassy in Colombia was in conversations with the FARC because the government wasn’t truly collaborating in my release.

I wanted to tell Margaret that I was alive. More than alive, actually. I was pregnant with a baby who would be born in two or three months.

Yes, I gave birth with a midwife. It might have been a member of the FARC too. It was painful. I had the experience of my previous two children, which means I knew what to expect.

[…]

I’m sorry: I can’t give more specific information about where Jardiel had been trained.

[…]

The baby was asleep when one evening, as all other captors were away, Jardiel said he wanted to take Jorgito away for a few days. I was frightened. He told me not to be scared. He wanted to bring him to his tribesmen. It was important that the baby was introduced to the tribe’s tradition. Jardiel announced: “To know your past is to sense your future.”

That took a total of five days. Jardiel requested permission for me to accompany him but obviously it was denied.

I prepared the baby as best I could. Jardiel got someone to feed him. They were away four days and three nights. I was in a state of desperation because I was sure the FARC had taken my precious son from me. That was a far stronger torment than anything I myself suffered during my captivity.…

One of those nights, I dreamed in Yiddish. I was in my house in Bogotá. My parents were with me. They spoke but I didn’t hear them. I was annoyed.

When they came back, my sense of relief was enormous. I was joyful to see Jorgito. He had lost almost a pound but he was fine. According to Jardiel, a tribesman had given him nutrients.

It isn’t true, as some media outlets have suggested, that Jardiel was an Israeli agent. He has nothing to do with the Mossad. This is said because people think Yiddish is the same as Hebrew.

Sometime later — I don’t know how long, though — French president Nicolas Sarkozy personally offered to travel to the Colombian jungle to negotiate with the FARC. I confess that by then, I wasn’t sure I wanted to leave. A long time had gone by. I felt close to Jardiel. He was a good father to Jorgito.

We spoke mostly in Yiddish to the boy. It was bizarre. We did it for one single reason: we felt so close to one another, we wanted to feel we were alone in the world. A bit like Robinson Crusoe.

We spoke mostly in Yiddish to the boy. It was bizarre. We did it for one single reason: we felt so close to one another, we wanted to feel we were alone in the world.

How would my family in Bogotá react when they found out I had a baby at forty-six? And that my son was Jewish?

I don’t believe Jardiel Poncela understood the degree with which his actions caused harm to others. He killed people but not because he hated them. He believed it was a means to a better future. He wanted Jorgito to also want a better life for everyone.

Along with fourteen other captives (I didn’t know them all), I was rescued on July 2 in what came to be known as Operación Jacque. As Minister of Defense Juan Manuel Santos announced, a series of military operatives — the media is calling them “spies” — had infiltrated the FARC. The captives, including four Europeans (Jacques Pointiere and Genevieve Bouchet from France, Luiggi Damico from Italy, and Iñaki from Spain) and three U.S. contractors (Thomas Howes, Marc Gonsalves, and Keith Strasell), were in several different locations. By a previously agreed time, the FARC “spies” managed to bring every captive to the same location.

We were all asleep when it happened. A battalion of soldiers arrived at dawn. It must have been around 5:30 a.m. Our guards, including Jardiel, were asleep too. The soldiers knew who was where. They shot them point blank. Jardiel was among them.

I woke up sweating. I thought it was a nightmare. Fortunately, I was able to get Jorge, who was two-and-a-half years old at the time. I held him tightly. My son was rescued with me.

In the jungle, I learned to listen to trees, to follow the light rivers reflect, to be aware of smells. The quiet of the jungle is precious. Modern civilization has forgotten what it means to live in harmony with other creatures.

The Partido Verde Oxígeno is in disarray. I hope it reconfigures itself one day.

My mother and father claim I was raped and the result is Jorgito. It’s a lie! My heart breaks apart when thinking Jorge won’t have vivid memories of his father. The government said to me yesterday that they recovered Jardiel’s notebook “with his scribbles.” I demand to have it back.

* […] denotes redacted segment.