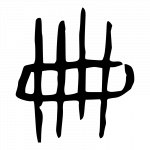

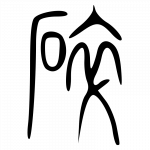

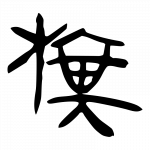

The word for book, in Vietnamese, is sách. This derives from the hán tự script 冊, a Sino-Vietnamese word. Through the many iterations of its form, the history for 冊 may be traced to one of the first documented origins for book, or rather the image of a book, carved into bone.

According to the Chinese paleographer Qiu Xigui, this origin for book may be traced, more specifically, to the Shang dynasty of the late 2nd millennium BC. In his monograph, 文字學概要, first published in 1949, he explains the nature of a text, quite literally, sinking into earth.

“The character ‘冊’ cè,” he writes, “appears in the shell,” which is neatly inscribed by a medium, an oracle, into bone:

Four vertical lines, the historian continues, represent strips of wood or bamboo.¹ The inner circle is unified. In other depictions, the circle is sometimes left open. In either case, Qiu Xigui explains, the inner circle — this inner circle in particular — represents a string that ties that book together.²

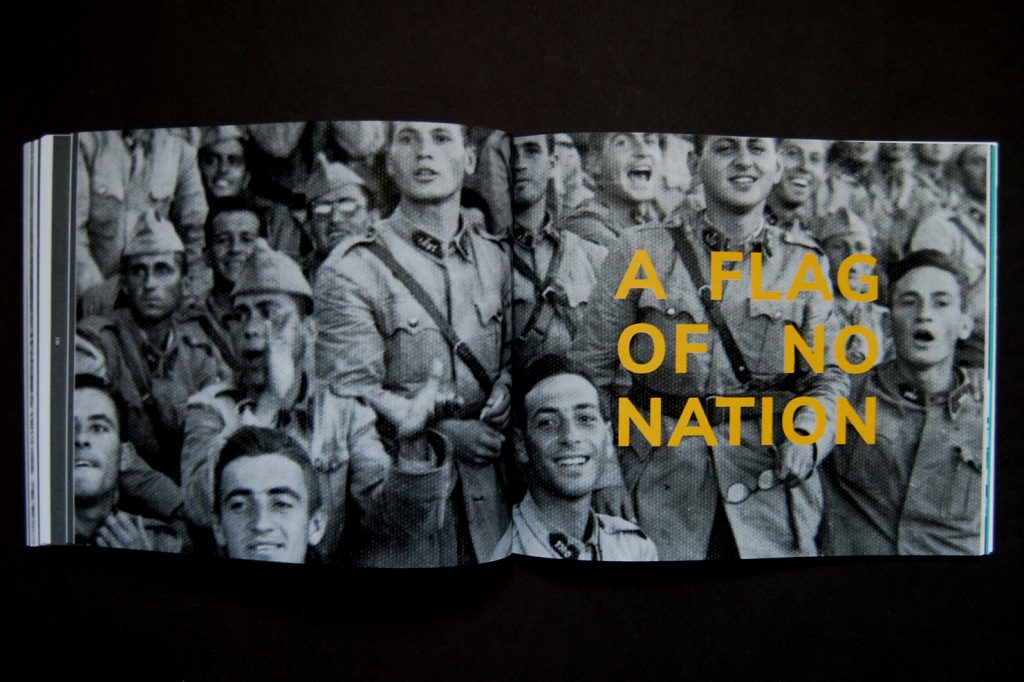

In a similar way, Tom Haviv — an artist and comrade whose work I’ve encountered in his debut collection of poetry, A Flag of No Nation — also writes about a lineage of language-making across time and space, of exile in the currents of his Jewish history. Whether the string between our many histories are tied at one end or open in nature, fluttering in the wind, is a matter of perception.

“Is there a pronoun between I and We?” Tom Haviv asks. A Flag of No Nation begins in this way: a register of scripts, twigs, and stone. They all seek answers, climbing a ladder, a flagpole, perhaps an oracular vision of ourselves in the future, tied to the past. How we answer his question, through taking inventory, photographs, and navigating the pages of his book, becomes, for us, an infinite branching of leaves into light. A subjectivity become ambiguous, malleable, and — most importantly — the book ultimately asks how we might choose to love over time, after exile.

That pronoun “we”

Tom and I first meet over the phone. It’s a dreadfully warm autumn day in Tucson, where I pick at the stones on my desk. In Brooklyn, Tom says, he imagines a great map swirling between us. And I feel myself smiling in agreement. Yes. His voice is warm, exuberant, and thrumming with light.

I want to ask Tom at least 500 questions about A Flag of No Nation. Instead, we chatter about the importance of altar-making, dreamwork, talismans, and, most vitally, of love. He also tells me about his family, the urgent work of his community and artistic practice as sites for “poetry as action.” In turn, I tell him about my Vietnamese mother, a refugee with whom I share a language. Though poetic, we speak in a tenuous space of patchwork English and of silences. Her history can therefore speak all by itself; thus everything I write becomes collaboration, too. At this, I can sense my new friend Tom, over the phone, nodding emphatically. Yes.

Through poetry, Tom also becomes a protector of ancestral knowledge and its many languages, both spoken and unspoken. The book, he explains, simply becomes a vehicle to “activate” that history inside of it.

Indeed, A Flag of No Nation, is an incredible force of movement, each section alchemizing into the next, as the author — a collective and multi-tonal voice across time and space — thus writes, “pronouns slip”:

together

pronouns slip

from finger

the song

was not

white not

my hands

obsessed with

holding

light

on my

shoulder—

In a moment like this, I’m reminded of the poet Fady Joudah, a Palestinian-American who once wrote, “I sing, in a tongue not my own: / We left our shoes behind and fled.”

The pronoun “I” quickly multiplies to “We.” Once again, protector of collective memory, the “We” then arrives at the shore of exile, looks around, and is therefore made alive by their own looking, made of flesh and blood.³ For that pronoun, “We,” in A Flag of No Nation, the poems act as palimpsest, clothing each voice in layers and layers of textures, The first time I noticed this, I felt as though a light had reached down, touching the top of my head. Before me sat the object of a book, its image transforming before my eyes into a talisman of no more nation.

A flag of no nation

In my mother’s Vietnamese, the translation for the word we is chúng tôi. This means, literally, a pluralizing of I (tôi: the single self made to be many, a collective of same-selves).

We can trace this image to its Proto-Katuic root of sool, which means slave. The Vietnamese language thus becomes, over time, for us, a language of enslavement. It’s been morphed, and continues to morph today, over the overlapping thousands years that precede us, ultimately leaping to the future, a shape of our many colonial occupiers.

A Flag of No Nation blooms with a similar self, multiplying to a unified body of document, memoir, stories, and poems. “The book begins in allegory,” writes Haviv, and throughout, the author’s grandmother Yvette Haviv makes that document, once again, a talisman. From the shore of a nameless island — both mythic and expansive in a shared imagination — to the voice of Yvette herself transcribed and rendered into lyric, Tom Haviv works across mediums — email, translation, photography, design — becoming yet another medium of bone.

The book is divided into six distinctive regions. It climbs, halfway through, from a “ladder / kicked down / from a window,” to define “allegiance” as a broken promise. Perhaps this allows us to imagine a different end to diaspora, one that delineates and circumvents the closed loop of history entangled in the violence of an occupied ancestry. In A Flag of No Nation, Yvette, a Turkish Jew, proudly declares her home to be “Córdoba: an unbreakable story.” We are then reminded of Istanbul, Tel Aviv, Ohio, the Ottoman Empire, and back to the 15th century, expelled from Spain. There’s a story here, in the map, refusing to make a line.

“In Palestine,” Haviv writes halfway through the book, “a war is escalating.” It’s simple. The terms are translated easily from one border to another. This breaks a poem in half. How do we write, after this?

Coloring our wars

I’m Buddhist. The prayer flags flutter around my house. I live in Tucson. This is simple. The flags of my religion are red, green, yellow, blue, and white. The flags make a circle around my house.

Over the phone, Tom asserts our shared responsibility is “to take care of this history” without erasure or departure from these contradicting truths. Indeed, as writers of our histories, we must cast such invocations of protection. To write, we read between a knotted legacy of exile and genocide. Our poems weave from the suburbs of Tel Aviv to the back alleys of Saigon. We must gallop, as we write, through wind.

Tom Haviv is the grandson of a woman named Yvette Karillo. She was the wife of a man named Israel Haviv. A Flag of No Nation lives in the present tense. I am the granddaughter of a woman named Huynh Thi Mai. She was the wife of a man named Le Va Tan.

How does a flag begin to climb itself, like the roots of a tree, when all the trees are dead? Exile defies its logic. Yvette writes, “How are you?”:

How are you?

Here white

is all around me.

On the west

side of my studio.

I watch

the pine tree leaves

wearing white gloves.

How do we meet as readers of separate histories? Is it possible to meet in the middle? More importantly, is it just?

Cờ đỏ sao vàng — what we know today as the flag of Vietnam, or the “red flag with a gold star” — first appeared to the public on record on November 23, 1940. There was an uprising in the south against our occupiers in Vietnam — then a colony of France, shortly after invaded by Japan. The uprising failed. The rest is known as history: a flag of red and gold.

“The flag is soaked with our red blood,” writes Nguyễn Hữu Tiến, a leader who was executed among others — scholars, organizers, painters, engineers — by the French on August 28, 1941. I’ve also learned through my research — separate from my mother’s Vietnamese history — that on that exact date, in a place called Kamenetz Podolsk, now in the western part of Ukraine, a German SS commander named Friedrich Jeckeln summarily ordered the massacre of 23,600 Hungarian, Russian, and Polish Jews.

A flag is soaked with blood.

In Vietnamese, the word for flag is cờ. This is derived from the hán tự character 旗, which is written — carved — into wood, a child of bone:

In his poem, “The Proper Noun of Love,” Tom Haviv describes a “silvered man” who begins to sing:

I began by describing the wrong tree. Its shadow is the tree falling.

I am the earth that has been uprooted by the tree’s falling shadow.

I began by attacking the root of the word. Why had we moved each particle?

Imagine this: a world displaced by shadows; in its place, a word. How do we imagine the first word of a nation?

As if in reply, the author writes near the end of his book, “Yvette Haviv (née, Karillo) was born in 1928, in Istanbul, Turkey.”

That year — 1928 — in Chinese astrology is also the Year of the Dragon, specifically, a dragon of the element 土, meaning earth. In the element 土, the dragons are quieter than most dragons. However, they are known to signify an optimistic spirit, its lucky color being gold.

“A golden year passes,” continues Tom Haviv, this time, near the beginning of his book, “the travelers are lost.” A human stands with the lantern. The lantern yawns open, revealing a sea. We’ve written this before, into stone, for what are the stakes of a language that extends beyond the nation of its origin? We answer, a collective sense of time, as one retraces every step into moonlight.

How does the “we” begin to speak without the “We” of history?

“The colors of the flag,” Tom Haviv writes as if in response, once more, “turquoise and copper, signify activation.” The Hamsa Flag, which closes out his book, is an extraordinary testimony of this activating power of community labor and love, which moves both alongside and beyond the text.

Toward the end of our conversation, Tom admits to me that he still has a “beginner’s mind.” And I’d like to think that is the best kind of mind to have in the middle of such histories, which only speak of endings; in Buddhism, I tell him, we must seek to nurture new beginnings, too.

For me, A Flag of No Nation, is an essential point of this beginning. And, like all spirited starts, it gallops forward in my heart. Beyond a doubt, the poem is a fundamental piece of spiritual and community work. It reaches both our altars and our bookshelves, thriving in the possibilities of hope, collective transformation. And like all spirited ends, that poem leaves us with more questions for each other: where do we go when we’re asked to go home? What is that origin of character for home in many languages, though none of them our own?

A Flag of No Nation activates that cry against us, pushing out the wind, just like a door, into our bones. Tom Haviv, collectively with ancestors and myth, has made a monumental text as one would make a talisman. That talisman might multiply, vibrating in its power:

LIGHT [Frame]

Through the flag, light [the activating agent]

falls. Sight is stimulated. Witness stand

underneath, flag overhead, walk together

to the nearest source of light. Brightness

passes through: copper, turquoise, white.

Witnesses, move closer, meet at center, make flag

slacken, pull again til it’s taut. Measure how it

changes under

fluorescence, tungsten, fire, sun.

Thus we walk together, toward our nearest source of light — that activating agent — as both book and flag, fluttering high above us.

A Flag of No Nation includes a later version of Tom Haviv’s essay “The Hamsa Flag,” published in Issue #1 of PROTOCOLS.

- Qiu Xigui’s monograph, 文字學概要, was first published in 1949 and was translated into English in 2000 by Gilbert L. Mattos and Jerry Norman.

- The hán tự origins for the Sino-Vietnamese words book (冊), self (碎), and flag (旗), in this particular essay, are Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG). These are public domain pictures of ancient script, from Wiktionary.

- See the poem “Proposal” from The Earth in the Attic (2008) by Fady Joudah.