i. Knowing and Unknowing

I was infected by L.’s tongue on a warm Friday night in July. His tongue massaging my anus; my eyes on his satisfied ‘90s heartthrob dimples and the curve of his intensely engaged pupils holding their focus on the warmth in my ass. An hour later, he sat on my kitchen counter in his red bikini-cut briefs and ate custard pie off a cold steel fork. Two weeks later, I was diagnosed with herpes.

The disease took its time with me so that within ten days my fingers, face, and asshole were infected. I felt like a breeding ground for visual signs of sexual impropriety. I was, of course, desperately depressed at the time, calling my friends and family, telling them how depressed I was. My body on the bed felt paper-thin, two-dimensional, pummeled with tiny disease-fists.

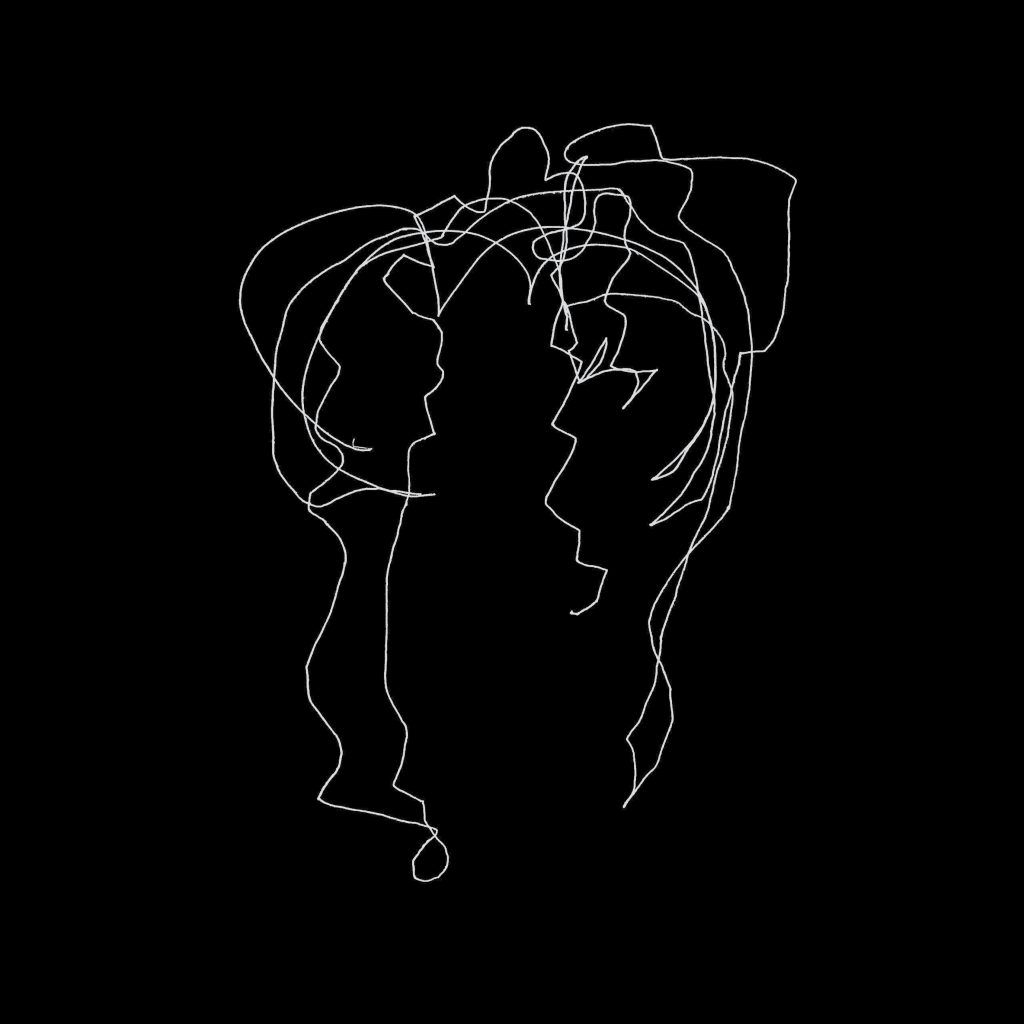

I’ve been thinking about thickness. Particularly, the thick fluidity of a river and how it relates to the flowing nature of a relationship. The way two bodies can create a special presence. The way L. was sure of his body and I was sure of him inside of me. Yet, with thickness comes unknowing: the unknowing of what is created between bodies.

+

I understand that herpes is a common, vaguely silly, and wryly stigmatized disease. I know I could have died of AIDS in an earlier generation. But without a full understanding of what it means to grieve, I am hyper-focused on the relatively harmless blemishes that mark my body. In Leviticus, God gets really concerned with who is tahor and who is tamei: who gets to take part in the rituals inside the mishkan and who does not, particularly in terms of skin lesions.

Some people have to be quarantined to see if their lesions disappear before they can once again enter the mishkan. In Leviticus 13:5, God instructs, “On the seventh day the priest shall examine him, and if the lesion has remained unchanged in color and the disease has not spread on the skin, the priest shall isolate him for another seven days.”

But some are said to be beyond healing. Rashi comments, “Consequently if it has spread during the first week, he is decidedly tamei, and no further quarantine is required.” Implicit in Rashi’s commentary is a message of care. Once the person is beyond recuperation, he is let go, no longer in need of confinement. There is thus a freedom to discovering and defining oneself as tamei. We can no longer enter the mishkan, but we can once again roam unfettered.

There is freedom in knowing and unknowing, but I find myself most sure in relationship to the categories described in the Torah. I like to know without a doubt whether I am tahor or tamei. I need a strong, wide line between “yes” and “no.”

+

Love is of course a rudderless undertaking: a thick, flowing thing among thick, flowing things that we try desperately to categorize, to make whole. We bring our multiple selves to every relationship.

Definitions of the self and the other are melted at best. We are made to move between each other. Yet, “Is he your boyfriend, fuck buddy, lover, fiancé, husband?”

I feel most comfortable when I know where along the spectrum I am heading with a man.

L., as you can guess, was not a long-term partner. Though I did see him a second time before I knew he infected me. My ex had fucked me the night before my second date with L. and I was feeling embarrassed. My asshole was leaking puss and blood—early signs of the herpes I didn’t know I had—and I was not feeling sexy.

Because I like to be as honest as possible, I told L. about the night spent with my ex and the liquid dripping from my asshole. He, in turn, told me that he’d hooked up with a meth addict the night before.

We finished our Indian food over light conversation and then proceeded to join a large crowd to dance cumbia in front of a government building. I pressed my lips to his closed lips at the end of the night and so we had returned to being friends. A clear distinction: I was free and thin again.

+

Aryeh Kaplan in Waters of Eden (1976) reflects on the mikvah, a small pool used in Jewish ritual. A person visits the mikvah for three primary reasons: after menstruation, for conversion, and for ritually submerging pots and pans. Kaplan states that the waters of the mikvah can be interpreted on their surface as a “cleansing agent.” But he argues that the mikvah in fact does not make one clean, for no one was unclean before submersion. Instead, the Torah ascribes to the mikvah’s waters a “change of status.” For instance, Aaron and his sons after fleeing Egypt entered the mikvah to consecrate their status as priests, or kohanim. Kaplan describes this shift as “an elevation from one state to another.”

I begin to wonder how herpes has changed me. In what ways has L.’s saliva worked in me like the waters of the mikvah?

+

“You’re maturing,” my therapist says, “You’re allowing another in. You’re softening.”

I tell her about the man I’m dating and how he knows a lot about my herpes. He and I spoke on the phone five times before we met and I mentioned it at least three times. And before our first kiss and first hook-up, I warned him about the disease and only made humming sounds when he asked me if we could have sex, but he knew what I meant. And he said, “If you’re not ready, it’s okay.”

Due to my vulnerability in sharing about the disease, he and I know each other’s brains and bodies more than anyone I’ve dated previously. But we are still early in the process of knowing an unknowable thing like two bodies.

I am, truthfully, still deciphering my own.

ii. White Jew

Frank O’Hara writes of multiple selves in his seminal poem, “In Memory of My Feelings.” These selves tend to glide and squirm. The words slither as they thicken his sense of personhood. O’Hara writes, “One of me rushes / to the window #13 and one of me raises his whip and one of me / flutters up from the center of the track amidst the pink flamingos.” There are so many bodies inside of us and they have reason to create friction, an unknowing between I and I. His selves, like mine, spill out over the poet and the speaker of the poem and into history and into empire and into violence.

The depictions of those bodies he inhabits at times rely on stereotypes of Arabs and Asians and Africans— “an African prince” or “an Indian sleeping on a scalp”—and so his selves also inhabit the white imagination, creating a thinness of “others” while it reimagines and perpetuates the thickness of a white self.¹ As a white man, I would often like my selves to stay hidden inside me, to stay small, but they tend to leap and bound in every direction and so I try to hold still.

In the past, I’ve attempted to paper over insecurities about whiteness with opaque poetry and metaphor; nevertheless, my white! Jewish! queer! imagination erupts. I am proud of my heritage and feel dense shame in my inability to perfectly understand or perform whiteness, a condition that is written on my skin—the obviousness of which eludes white supremacists. I am undoubtedly a thin caricature to them: a nose and a brain. And then of course whiteness is the thickest and thinnest affliction of the skin and the mind; it irons out and codes every face, imperceptibly and obviously. I look in the mirror and wish for some divine ability to unknow whiteness. Instead, my selves stay stock-still and try their best to sing with one voice.

iii. Grief as Unknowable

Suddenly, it’s impossible not to think about bodies that are no longer here. My friend, K., died last year. His body was fleeting but his spirit is thick. He has an explosive laugh. He has dark circles under his eyes. His skin is pasty. His smile is mischievous. His lips are purple. His cheeks are puffy. He plays the Donnie Darko theme song on his parents’ piano. He draws penises and portraits of his exes. His body is free from hair except for around his belly button. He sends me nude pictures of himself. He and I never have sex. We are always friends first, even though the line is always there to cross.

+

I begin to imagine grief as a perpetual state of tamei. I am always clogged with the knowledge of my deceased friend. I am always diseased with the grief of recovery.

What is the category of tamei if the corpse is inside me?

+

Grief is as thick and fluid as blood, as song.

He and I are one but in an unsettled way.

We roam outside of the doors of the stars

and surround the whorls of dust.

We thicken alone together.

iv. Onenesses

I’d like more than most things in the world for this essay to turn toward oneness. I’ve been preoccupied with oneness for some time now. After my friend died, I felt his presence in my room, in the same spot every night, and I could see him smiling at me with his quizzical and warmly condescending smile. And this felt like I had reached a oneness with him that I had not known in reality. And so I’ve been singing the shema in his honor any chance I get—in shul or in performance or alone in my apartment:

שְׁמַע יִשְׂרָאֵל יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ יְהוָה אֶחָֽד

Hear, O Israel: Hashem is our God, Hashem is One.

I see the shema as a compression of time. A community of one. There can be more energy generated when all of your energy is focused on one person, one being, one truth, one line blending two people, even if one of them is no longer breathing.

In the Likutei Moharan (Torah 65:2–3), Rebbe Nachman writes of prayer as a collection of onenesses. As a person recites letters and words in prayer, “he is gathering beautiful buds and flowers and blossoms, like someone walking in a field picking lovely blossoms and flowers one at a time.” He compares this gathering of letter by letter and word by word to the oneness of God.

And then because it feels very natural to do so he considers the oneness of God as the “ultimate goal [of Creation]” that is only accessed, he writes, through intense focus, needing to shut one’s eyes, “even pressing a finger on them to seal them shut.”

I can imagine the whole world, the complete world, whole in R. Nachman’s imagination using his intense focus for purposes of clarity and oneness. And so he makes these strides toward oneness, toward a fuller imagination.

Ultimately, he’s trying to make something that’s very thick into something thin enough to hold in our skulls. Or maybe we’re just not there yet? It’s all too thick to take in. The flowers keep blooming and it’s impossible for us to truly achieve his degree of oneness.

v. Merged

“As if by being inside me, he was this new extension of myself…as if we were two people mining one body, and in doing so, merged until no corner was left saying I,” Ocean Vuong writes—quoting Simone Weil—in On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (2019). The pleasure and pain allowed for his narrator, even while being penetrated, to continue to fill his brain with an aura of oneness under a circle of golden light.

+

As if his narrator is a living being inside me.

As if his narrator is inside him but also a circle of the dead that is yet to be awakened.

As if his narrator is also my voice.

+

Is oneness possible between two people?

Or is there always an unknowable film between us?

I want him to close his eyes, pressing them firmly with his fingers and then for his tongue to lick the paper-thin version of me. I want him, and I pretend we are one.

vi. Song

In a chapter of The Queen’s Throat: Opera, Homosexuality, and the Mystery of Desire (1993), Wayne Koestenbaum sorts through a stack of vintage how-to manuals for singing opera. He says that the manuals are written for amateurs because real singers don’t need manuals.

And so we are with him, among the amateurs, awaiting the full blossom of rules from the instructor’s velvet throat while we begin to decipher the mysteries the opera divas are willing to part with.

I’m taken with the title of one section of the chapter that reads, “Singing v. Speaking.” The section is short but gives me a lot to consider, as with this warning by diva Maria Jeritza: “So many girls do not seem to realize that the speaking voice is actually the enemy of the singing voice.”

I begin to wonder whether this is what R. Nachman is describing in prayer. There is a focus to it—and a chanting and a singing and lifeblood—that begins to cast out all of the daily muck of life, even the worst suffering, he says. Oneness is not achieved in everyday speech, but in deep, soul-searching revelry.

In Koestenbaum’s analysis of Jeritza’s quote, he responds, “If you speak a secret, you lose it; it becomes public. But if you sing the secret, you magically manage to keep it private, for singing is a barricade of codes.” Singing breeds an unknowability, a reason for living, a way to vibrate like the shadow between two bodies. Considering Koestenbaum and R. Nachman’s theories, perhaps the secret to oneness is buried in song.

+

I think about the way I stop when L.’s tongue is inside of me.

I think about the way the music stops in my mind when I’m really concentrating.

A moment later his tongue widens and the pleasure it releases feels like one small voice

singing all four parts of the same song.

- When addressing whiteness in relation to the Frank O’Hara poem, I refer to Sara Ahmed’s “A phenomenology of whiteness,” Sage Journals vol. 8, no. 2 (August 2007): pp. 149–168. I also refer to Claudia Rankine and Beth Loffreda’s introduction to The Racial Imaginary: Writers on Race in the Life of the Mind (Fence Books, 2015), pp. 13–22.