After Anne Boyer.

I wanted to write about history the way I used to write about care. Like care, history both requires a human and baffles us. History laps over the human, needing us as an object but having little to say about the particular.

I wandered a city where bodies like mine had been, and had been killed. I was tracking not our stories but instead the uses of the word fascination, its roots in the prefix fasci, which has been my project and obsession for a while now. I had been looking for fasci everywhere, but until now not in person, not in the country on which fasci insists. I stalked this city for fasci, seeing first posters and rants. I stalked the archives, memorialization well intact in their careful and exacting collections. For my etymology and definitions I stalked the internet only. Fascination because I couldn’t stop looking, and the people here couldn’t stop looking at me. Fasci because some of them had bundled together to kill us, and they continue to rise.

When Jenny posts about fascination it is not about an attack but about plants. She posts a picture of a long strip of crumpled flower running across the top of a gray-green cactus, and in her caption explains that this is a mutation called fascination, in which the plant develops its flower in a wavy horizontal line instead of blooming erect upon one single point.

I pounce. It ends up being a slippage, a mis-hearing; the plant mutation is actually called fasciation, no “n” in that second syllable. But the word still has its roots in the prefix that I love.

I hear the prefix, of course, because I have been waiting for it. Fasci is a home I’ve made for myself, to the extent that even when I am swiping or scrolling I have its structures in the back of my mind. I am surprised not to have encountered this plant word sooner. Fasciation, I read, literally translates to “banding or bundling,” or “the act of binding up,” the same way fascism came from the Italian for a bundle of sticks, this same bundling now a flower band.

Fasciation can occur because of a shift of hormones in the plant’s cells, because of genetic mutation, or because bacteria or damage on the growing tip of the plant causes it to shift the course of its growth. When plants develop this mutation, their flower forms a cylinder, and fasciated flowers often look flattened, like long ribbons or undulated folds. In some cases, these folded flower heads are prized and bred intentionally, as in the case of the cockscomb celosia. Most sources say the cockscomb got its name because it looks like the top of a rooster’s head, but my sense of humor knows better than that. Fasci is heaven for dick jokes, and I’m not decent enough to resist.

I am working in the archives at the Jewish Museum in Berlin, trying to feel professional even as I flip through cartoons exaggerating Jewish noses and phalluses, even as I bring my own lunch in a messy Tupperware wrapped in several reused plastic bags. Mid-morning I am already worried that my lunch is leaking into my backpack, so I take an early lunch break. I bring my Tupperware safely out of the library and decide to sit and eat it in the Garden of Diaspora: the courtyard positioned right in the middle of the W. Michael Blumenthal Academy — the building in which the archives are held.

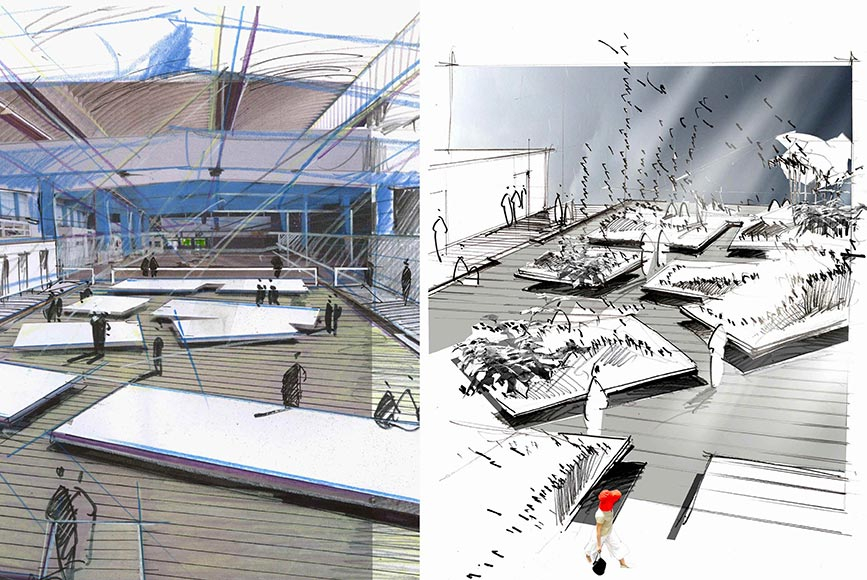

In the introductory text for the Diaspora Garden, I read that it was designed to represent the Jewish diaspora, and includes plants “with a special connection to Jewish life or Jewish personalities;” plants in various stages of “seeding, rooting, growing, and wilting;” and plants in a “‘diaspora’ process in the sense of dispersion.” The plants sit in beds on “floating plateaus” or wooden platforms that appear rather makeshift, reflecting, the pamphlet reads, “aspects of life in the Diaspora.”

I crouch in a corner because there are no chairs, but suddenly want to know every word about this space. I pull up the audio guide on my phone and poke in my earbuds. I hear that the Garden evokes “literally the dispersion of people who have left their traditional home.” I look up at the plants suspended from the ceiling. I am uncomfortable in my crouch but also feel suddenly frozen. I turn to open my containers of packaged sauerkraut and hummus and place them on the wooden floor next to me along with my half-melted compostable fork and scrap of paper towel. “The plants come from different climate zones and have to adapt to their new unfamiliar environment.” My ears are sweating around my earbuds. I stand, dizzy, and take a stroll around.

From the looks of it, it doesn’t appear that adaptation is going well. The Garden’s plants look scraggly, under-watered, and crawling from their beds toward the floor. The audio guide ends and all I can hear is my own feet creaking on the wooden planks I walk across. I do not like it here, even with the abundant air, natural light, and potentially charming climbing vines. I return to my corner, and wonder for a moment if it’s allowed to eat in here. I take a few hurried bites and feel embarrassed about the smells emanating from my containers, even though no one seems to be around or near. It is very, very quiet. In background of the audio guide, a person hears the sounds of birds, but not in here. Nothing lives in here but the plants in their beds. I stare. The plants look back at me, inert, almost lifeless in their limp sprawl. I feel a rising nausea, not sure whether it’s about how quickly I’m eating, or this place.

I stand, wrap my containers in their plastic, and, dazed, make my way toward the exit. Near the doors I pass a pile of thick plastic bags with drainage holes, which I recognize from the audio guide; they are intended for children to take small plants from the garden home with them so that the garden is “continually in the process of dispersion.” I walk out of the Garden and into the Academy’s bunker-like bathroom. I sit on the toilet until my nausea subsides.

I wanted to write about history the way I used to write about care, but did not want to be cared for from a distance. I wanted to lie down inside of care, but not to dissolve inside of pity.

In Ways of Seeing (1972), critic John Berger notes that “when we ‘see’ a landscape we situate ourselves in it.” He writes here primarily of two-dimensional artwork, but I feel the same way about the exhibition of the Diaspora Garden, almost forcibly so. I am invited to understand the garden as a Jewish story and so necessarily to include myself in it. What disturbs me is the exhibition of diaspora as a story specific to Jewishness. I feel pinned to the wall, the way some of the vines in the garden have been pinned to lengths of rope in an attempt to lead the plants toward the ceiling, though they twist away from the rope and yellow where their roots protrude from the dirt.

I am invited to understand the garden as a Jewish story and so necessarily to include myself in it. What disturbs me is the exhibition of diaspora as a story specific to Jewishness.

Later, I ask my friend Berivan about the Garden. Berivan used to work for the Blumenthal Academy’s “Academy Programs,” and we’ve already rolled our eyes together about how the building’s renowned architecture isn’t built for actual humans to work inside. I ask Berivan if it’s on purpose that the Garden is on the messy side — I know it’s won many prizes for landscape architecture, and I want to assume thoughtful intent. Berivan laughs.

“Definitely not,” she says, “it’s just that no one is taking care of it.” She tells me that the Garden has been semi-abandoned as museum staff move on to other priorities. But, she explains, she spent plenty of time in there during her time at the Academy. During one work event, she tells me, she used the Garden to explain to colleagues the inter-religious and varied symbolic history of the plants included. Berivan begins telling me about the seven biblical species featured in the Garden: the fig, the olive, the date, and others. I love that I am standing in an apartment in a Turkish neighborhood in Berlin with my Kurdish-German friend, listening to a list of plants that was bored into my brain in Hebrew School from very young. I remember crouching in a Boston suburb at a long table around a blue-and-white plate of these same fruits, 12 of us feasting on one single bruised but preciously imported fig.

“I learned about these plants like they were from far away,” I tell Berivan. “They were exotic to us, too.” Berivan is about to finish her thesis on Kurdish genocide, repression, and diaspora, and I do not need to lecture her about the mythologies of original landscape, but I do. Somehow I feel the need to say it still.

“The minute you began talking about plants, you are also talking geography.” I shake my head, and can’t stop shaking it. In the Diaspora Garden, nation-states are not named as the origins of each plant, but most of those present originate in the Middle East. The thing about the Diaspora Garden is that the plants do have roots. They reference a place, a ground, an ecology of dirt, but in the bright courtyard they do not touch the German outdoors, the native soil. They are root-bound in their containers, held there for the sake of keeping the exhibition intact. They imply an indigeneity—one that is interrupted, held constructed in air—but tied even in this interruption to a single place of origin. What upsets me is the sense of exception here: the story that the Jewish diaspora is exceptionally dispersed, continually and expositively so, whereas all other peoples are rooted on solid, constant ground.

I tell Berivan about the first day I worked in the archives in the Academy, how I walked into the stacks and felt tears spring to my eyes, my body suddenly sagging against the steadiness of a metal shelf.

“I felt like I’d arrived,” I say, “where I belonged.” I hid there against that shelf, turning away from the librarians so they’d think my weeping was just deep concentration on the volumes of collections about Jewish ethics. I tell Berivan I didn’t know then if my weeping was a feeling of belonging in a library, or belonging in a Jewish institution, or the legitimacy and validity I felt working in the archives, in such contrast with the tenuous professionalism of a freelance writer. “But I actually cried,” I tell her, “longing so hard to be home.”

Berivan pulls me in for a hug, and I am surprised by its quickness.

“We know home is bullshit,” she says softly, and I can feel her wide smile as she breathes out quickly close to my ear, “people have been moving always, so our home is with our people.” She pulls away, strokes my shoulder, and laughs, and we laugh together at how basic this sounds.

“I mean, I don’t want to be one of those rootless cosmopolitans—” she gestures into the rainy Berlin street, “who don’t give a shit because they don’t believe in home.” No, it isn’t that. Not to be cosmopolitan, wandering the great cosmos without ties, relations, or obligations. Not to deny trauma, but also not to force home to grow suspended from the State.

I wanted to write about history the way I used to write about care. Most humans I know are baffled by care, even if they want it. They want to be cared for, but when the light of care turns upon them, a role is required and they aren’t prepared to play, to be taken in. So too history: the body taken in, washed through.

I lay down in history looking for my own body, listening for the sounds of my own familiar breath. “I mean, having a body in the world is not to have a body in truth,” writes Anne Boyer, “it’s to have a body in history.” I lay down at night in Berlin and listened to phrases whisper through my mind: fascism, fascination, fascinum, fascinare. How very diasporic of me: to place myself in the country and let its words assimilate into my consciousness, into what I want to consider. I place myself in speech and wait for it to soak me through.

Many writers have turned to words for their landing place, and when I look to land, I return to some of my favorites. John Berger, in And our faces, my heart, brief as photos (1984), writes:

The boon of language is that potentially it is complete, it has the potentiality of holding with words the totality of human experience. Everything that has occurred and everything that may occur. It even allows space for the unspeakable. In this sense one can say of language that it is potentially the only human home, the only dwelling place that cannot be hostile to men.

I pursue my home here, in the fasci root that stretches across language and genocide and people and movements in time, a moving target that admits history and also evolves, un-landscaped, incomplete.

I fly away from the city and the Museum, the Academy, the archives. I go back to where I live now, but resist calling it my home—to Oakland, where I have lived the longest, the city where I try to commit myself without claiming mine. I continue writing this book on fascination. In pursuit of fasci, I buy cockscomb seeds from my local hardware store after putting them in my cart on Amazon then feeling too guilty to complete the transaction, knowing better, wanting to be better.

In line to pay at the hardware store, I look at the bright flowers on the tiny packet. I pass the tiny package to the cashier, vaguely annoyed about how much time it has taken to walk here to the gardening store and will take to walk back. Home, I wish to be efficient. I rush. I rush through this, this idea of planting fasciated seeds, even as I want to see the plants for myself, to grow them for my own. I bring home the seeds and place them on my kitchen table, though I haven’t even checked yet if cockscomb will grow in my climate, or in the amount of light I can make available to it. I tear open the seed packet quickly, and it gives me a savage paper cut, as if in revenge.