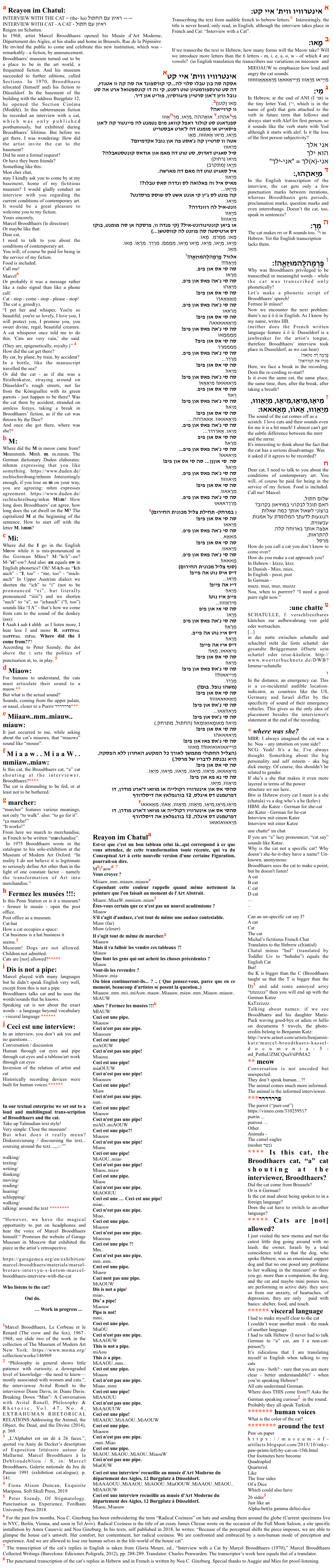

“This is an interview, recorded at the Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles, 12 Burgplatz Düsseldorf,” announces the interviewer. “MIAOW! MIAOW!” replies the interviewee. In 1970, the Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers (1924-1976) conducted and recorded an interview with a cat. At the time, he was the self-announced director of a fictive museum: the Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles (1968-1972). The location of the interview — 12 Burgplatz, Düsseldorf — was home to Cinéma Modèle, one of twelve sections of the museum. The time and place are set, and a conversation begins: — “Is that one a good painting? […]” asks Broodthaers. “Miaow,” replies Cat.

Up until today, museumgoers pay greater attention to the artist’s questions than to the cat’s replies, and so the discourse on Broodthaers’ work mainly focuses on his words. But why? Actually, the cat, the interviewee, is the main protagonist. Once we tune in to all the voices that can be heard in this conversation, what do we hear? This essay sets out to listen attentively. We attempt to tie the two parties together in a shared alphabet and transcribe the conversation between Broodthaers (B) and Cat (C) anew. This unprecedented endeavor is mirrored in the typographical layout. Our textual enterprise takes a Talmudic form, putting in its center the dialogue, transliterated from utterances in French and Cat tongues into Hebrew and Latin letters, and opening up threads that introduce questions of translation and interpretation.