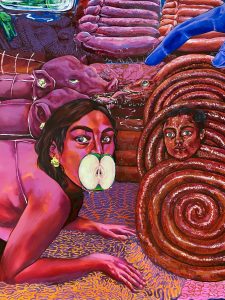

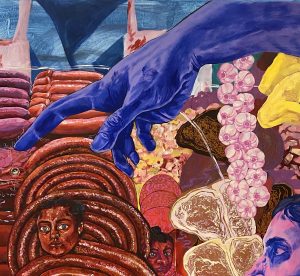

There is a certain regal grossness to a Jewish deli case. Teeming with pungent delights, it looks something like a fluorescent Eden, its glass walls packed with kosher meats, pastries, smoked fish, and salad plops. The goods in a Jewish deli case look, frankly, corporeal — salamis corseted in twine netting, pink piles of limb-like kishka, the wart-ridden skins of kosher dills — so it’s not hard to see where Rosabel Rosalind gleaned the inspiration for her painting, Fresh Meat (Counter Culture) (2020), on display in her studio at Carnegie Mellon. Rosabel swaps out the usual deli fare for an imposing feast of antisemitic iconography and allusion: sharks stand in for loan sharks, sausages curl into serpents, hooked noses sit among the cheeses as circumcised scrota pickle in jars. A self-portrait of the artist pulls our focus to the center: with a Jude tag on her ear and an apple between her teeth, she looks like some version of Eve, her body bound and at the mercy of the sinewy blue hand of God, outstretched to purchase and pluck her from her perverted paradise.

While on a Fulbright scholarship in Vienna to study antisemitic propaganda, Rosabel noticed a theme: Jewish people were almost always represented as non-kosher creatures— pigs, rats, snakes and insects— and as such, in Fresh Meat, nothing is kosher. A faceless yarmulke-clad deli customer looks into the case, their reflection juxtaposed upon the propaganda-fest. One must wonder if they feel any kind of familiarity, or even identification. Mingling propaganda with self-portraiture, the question Rosabel’s work seems to ask is one of reclamation: what happens if you see yourself reflected in what’s meant to be used against you?

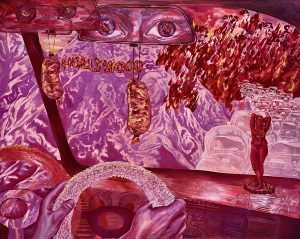

Somewhere in the same meaty universe, Rush Hour (Over The Hill) (2021), also on display at Carnegie Mellon, depicts a figure trapped on a Los Angeles freeway driving towards a distant blaze, the Hollywood sign spelled out in sausage. We can’t see the driver in full, but their eyes resemble those of Eve in Fresh Meat, wide and fixed beside a narrow nose-bridge. The glass windshield is akin to the glass front of the deli-case, so I can’t help but imagine this work as Fresh Meat on the move. The hot sherbet sky recalls this past summer’s wildfires, the orange haze that rose over California as flames crisped the state’s touchstones — its blue skies, redwoods, and brush-laden mountains — to apocalyptic props, cinematic nightmares straight out of Blade Runner. This imagery plays on conspiracy theories old and new: Jewish control of Hollywood and the recent claim from QAnon faithfuls that the California wildfires were an act of arson via Jewish space lasers.

Of all the deli’s items, Rosabel fixates on the sausage, a mix of parts ground up and shoved back together into an intestine that both orders and conceals the messy nature of what lies within. The sausage is a subversion of the body, a defiance against any kind of human form; this notably makes it immune to propaganda, for it’s difficult to exaggerate something shapeless and inhuman to begin with. The sausage both embraces the wares of the deli and shields them from objectification; in some ways, it seems similar to modern Jewish identities—an amalgamation of history, legend, and trauma piped into new casings, new generations postponing the decay of history. Hanging from the mirror, the sausage seems both a protective talisman and a key to the city. Here, Hollywood is the home of the sausages; Eve’s been granted entry in, only to find herself trapped in traffic, headed towards certain barbecue.