“Talmudic War Machine & A Shadow’s Dream” is an attempt to write and dream the sitra achra from “within” — from within the realm of darkness, provoked by an aporia, an indissoluble knot of existential contradictions. It starts from the assumption that the individual and collective disasters of the 20th century and their forces of war, death, and destruction have caused what the Lebanese artist, thinker, and filmmaker Jalal Toufic calls a “Withdrawal of Tradition Past a Surpassing Disaster.” The Talmudic tradition itself has been subject to such a withdrawal, its diasporic ways of thinking occupied or hijacked by doppelgangers and look-alikes loyal to territorial politics, to public economies of guilt, memory culture, religious pop, national flags, and other digests. In the grip of these doppelgangers, (Jewish) tradition feigns visibility, availability, and accessibility in the midst of its withdrawal, its inner secrets turned inside out, flipped to the surface, sold, and catered to consumers’ tastes.

In such times, sanctity, joy, faithfulness, and love of tradition may hide in foreign contexts, where lovers and learners claim their right to opacity beyond the doppelganger’s grip, beyond visibility and surveillance. Is it possible that holiness and the sitra achra have switched grounds without anyone noticing, providing pathways of escape for endangered traditions? This essay explores those abysmal shifts, which lead us on to regions deeply embedded in artistic research and personal oneiropoiesis. I therein follow the escape paths of what psychoanalyst Karl Abraham called the “Talmudic way of thinking,” into artistic and poetic regions that are radically idiosyncratic. From within such idiosyncrasies, the sitra achra may provide miraculous cracks and loopholes for fragments of traditions and their secrets to “return” backstage.

Not long ago, in the context of some research motivated by a strictly private matter, I came across Karl Abraham’s phrase in a personal letter from him to Sigmund Freud dated May 11, 1908: “Surely, the Talmudic way of thinking cannot all at once have vanished from us.” The context of this remark was a conflict between Abraham and Carl Gustav Jung, brought about by divergences on libido and sex theories at a conference in Salzburg the same year. Abraham’s line — “surely, the Talmudic way of thinking cannot all at once have vanished from us” — was a retour to Freud’s mentioning of Jung’s intellectual upbringing as “a baptized Christian and son of a pastor” in a letter before, emphasizing that he, Jung, is joining “us” against “huge forces of inner resistance.” The methods of psychoanalysis, Freud and Abraham agree, demand at least a faint bodily memory of what Abraham calls Talmudic thinking. However, Freud immediately adds, psychoanalysis should by no means be taken to be an exclusively Jewish affair. Abraham and Freud rather seem to point to a shared “intellectual constitution,” a specific practice or habit of thinking that Abraham calls die talmudische Denkweise — the Talmudic way of thinking; a “pathos formula,” a performative gesture and ephemeral move of tossing and turning around letters and words in ways in which the ancient masters used to do it, knowing how to touch them, trace them, mirror them, conflate, cut, veil or unveil them, undoing referential regimes, unhinging grammar, sidetracking metaphors, proceeding from outside in, from answer to question, in a typically Talmudic flow of free associations, taking its cue from word plays, semantic hides-and-seeks, triggered by the imagination, by desire, fear, and dreams. The ancient rabbis refer to this play traditionally by the name of a love toy — “I was his constant delight [sha’ashuim], playing daily before Him” (Proverbs 8:30). The Torah is God’s play toy, and thus the play toy of the ancient rabbis. Sha’ashua means literally a pleasure toy (erotic connotations included), a lifelong language game that is meant to sustain the entire universe, yet not be used for anything, a game play of jouissance, which is the rendering of sha’ashua into French coined by those who still remember “the Talmud.”

Let’s not forget — the Talmud! Vergessen wir nicht — den Talmud! Is this then the subtext of the small booklet Vergessen wir nicht – die Psychoanalyse!, published by Suhrkamp in the year 1980 with four essays of Jacques Derrida on matters of psychoanalysis? Let’s not forget — the Talmud! And why does it seem of utmost importance that we, who have not even a faint memory of the Talmud, do not forget Talmudic thinking? Berlin Institutes of Religious Studies, Literature, Cultural Studies, and especially of Psychoanalysis can no longer claim a memory of Talmudic thinking. Talmudic thinking in Berlin academic and psychoanalytic institutes belongs to those traditions that according to Toufic have withdrawn past a surpassing disaster. Does that mean books, libraries, even lectures or seminars in Talmudic thinking are not available or not possible at those institutions? Of course not. Of course they are not only possible but also happening, sometimes in abundance. What is it then that is not available when speaking of a “Talmudic way of thinking”?

Toufic coined his phrase “The Withdrawal of Tradition Past a Surpassing Disaster” in reference to an immaterial withdrawal. Such a withdrawal, he says, is caused by a specific kind of persecution, war, mass murder, genocide, colonial occupation, or other violent acts that not only materially destroy people, buildings, and the infrastructures of a community during the time of the disaster but also have long-lasting effects on the tradition itself. These, to Toufic, are immaterial effects, attested to by people sensitive to the withdrawal, members of the community affected by the disaster, writers, artists, filmmakers, psychoanalysts who can no longer access the tradition after the disaster, even when books, libraries, institutions, and other remnants of it are restored or remain materially available. The tradition itself is irreparably damaged.

The Jewish tradition, too, is subject to such a withdrawal past a surpassing disaster. After the disaster of German and European fascism and mass murder in the 20th century, the Talmudic way of thinking has immaterially withdrawn in the midst of a material availability that is possibly more abundant than ever with very few sensitive to this withdrawal. I have shown this on several occasions, especially in my House of Taswir – Doing and Undoing Things. Notes on Epistemic Architecture(s) (2014).

The damage gets worse when the tradition gets hijacked or occupied by those who are not sensitive to its withdrawal, treating it as if it were available, producing look-alikes, doubles, doppelgangers, fakes, and counterfeits that make it impossible for the withdrawal of tradition to even become visible.

“What we encounter here is a painful difficulty, a deadlock, an existential and quite personal aporia, indeed an awareness of failure, of what it means for a Jewish she-intellectual to explore her lines of flight and to decipher texts, images, or other objects…hijacked by politics of collective representation; of what it means to read these things “just the way the Rabbis did” in the midst of…a public…warding off any possibility of fundamentally questioning the colonial presence of a Jewish apartheid state in the Middle East, sadly confusing this denial with the obligation towards the survival of the Jews and of Jewish tradition.” (House of Taswir, p. 195)

After the Shoah, the fidelity of German state institutions to the “Jewish State” produced Jewish Studies departments and other historic or literary fields, creating a whole swarm of doppelgangers posing for matters of Talmud Torah. Matters of the Talmud have turned into academic or communal areas of literature, religion, history. The Talmud’s techniques of deterritorialization, its meandering paths, acts of dislocation, its thinking from the margin, its brilliant lines of flight have been hijacked and bent into obedience to the State — notwithstanding outliers such as Daniel Boyarin and many others, speaking from outside the German condition. In psychoanalytic contexts this coup, cover up, deceit is especially painful for those who are sensitive to the immaterial withdrawal of Talmudic tradition. Why? Because Karl Abraham was right: Let’s not forget — the Talmud! In times in which portraits of Abraham have become decorative counterfeits in psychoanalytic institutions, cover-ups for their dark chapters of ethnic cleansing, the immaterial withdrawal of Talmudic thinking becomes entirely eclipsed, made invisible by a veil no longer revealing anything at all, leaving no trace of its disappearance. How do we enter then? How do we enter a doorway sealed by a doppelganger’s perfect mimicry, invisibly veiling the withdrawal of tradition past a surpassing disaster?

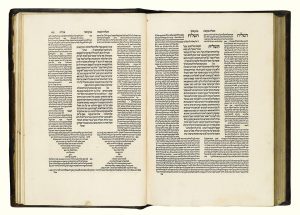

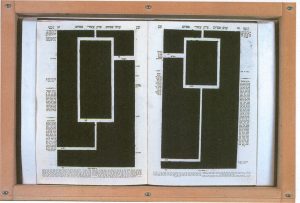

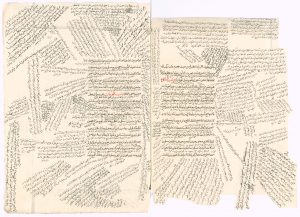

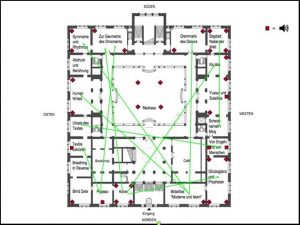

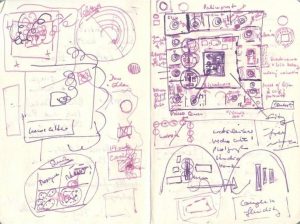

There are two ways of escape I can think of when facing this mental and existential deadlock: one is connected to architecture, the other to dream-work. The first pertains to the development of an architectural device working as a shibboleth for the tradition to pass doorways that are sealed by mimicry and doppelgangers. For about fifteen years now, I have developed such an architectural device. Providing lines of flight for “Talmudic thinking,” I took the very architecture of the Talmudic page and turned its very format into exhibition sketches, staying true to its external form, its dynamic gist, its meandering paths, its side-tracking signifiers, its semantic associative chains behaving — in the words of Deleuze and Guattari, “anexact yet rigorous.” These chains I turned into object constellations criss-crossing time and space, just as the letters on the ancient page. In these exhibitions, whether large or small, I started to switch art objects for letters, emulating the very gesture of the Talmud’s kinetic moves. We recognize it in a medieval folio of a Hadith, too.

Those epistemic architectures of the ancient page inspired most of my exhibition sketches and their subsequent spatial settings.

Of all the visitors who came to see the exhibition Taswir at Martin-Gropius Bau 2010, with over 50 artists and 20 international collections of classical Islamic art, there was only one visitor who realized that he was standing in the middle of the page, who knew that despite its title — “Islamic Visualities and Modernity” — this was not a thematic exhibition on modernity and Islam but a rescue operation for repressed ways of diasporic thinking.1

Today, due to reasons private and political, I think it is time to embark on an additional route. It is time to disentangle the “Talmudic way of thinking” from its doppelganger’s grip in yet another, more explicit way. It is not enough to emulate, displace, shift and transform architectural formats of the Talmudic page. We want to be in touch again with the Talmudic material, its letters and words, without becoming forgetful of the doppelganger’s hijacking mimicry. How to do that when its nomadic ways are being denied, its lines of flight hermetically sealed?2 From now on I am asking you to follow me into largely unexplored territory, as I came to realize that rabbinic material needs idiosyncratic exposure to keep it away from all generic discourse.

Some time ago, when the strictly private matter had reached a devastating deadlock, the Talmud, through a dizzying detour, recommended itself to me inside a personal dream scene that, on its face, had little to do with anything looking even remotely Talmudic. But it turned out that some Talmudic passages I had studied with my beloved rabbinic teacher in Jerusalem, the Rav Walter Zev Gotthold, and completely forgotten about had sneaked into these dreams in absurdly deranged contexts, off-territory, bypassing all those deadlocks sealed by the doppelgangers I have learned to recognize so well.

I will read you the dream text as it appears in the private dream diary of the dreamer. The dream is called “The Dessous of the Moabite Lady” and I dreamt it on the night of the seventh light of Chanukka. The question that arises in the dream is: How do we “shed light” on what needs shadows to survive? How do we contest visibility? How do we protect our right to opacity in times of total transparency in matters most intimate and private? How do we create lines of flight for lovers?

Dream Diary, Dec. 19, 2017, 10:36 am:

Two lovers embrace on the bare floor of the small blue room with the red couch. It is pitch dark; the two lovers feel comfortable and undisturbed, they are in the middle of a caress, the time passes slowly. Steps are coming from the corridor. The psychoanalyst opens the door and enters. It’s still dark. Their floor spot starts to move. In a slow but constant shift [the German word here is “verrücken”] the floor moves their scene of love gently away from the door. The lovers feel not the least bit disturbed or distracted. The strong light cone of the analysts’ flashlight contrasts sharply with the dark in which the lovers feel safe. The analyst is looking for something, her flashlight searches the room, the cone never hits the lovers, her light cannot perceive them, they remain in the dark without any effort, gently displaced by the floor carrying them away from the light with great reliability. The lovers always remain in a spot where the light is not.”

What is the story framing the dream? Where does the Talmud enter? Two lovers who had issues with some external psychoanalytic setting fantasized to enter a psychoanalytic space together.3 Clearly the dream brings up the question of how the secrecy of their love escapes the surgical intervention of psychoanalysis. What is interesting, however, is the way in which the dream quite elaborately specifies the movement of their line of flight. In the dream, the lovers escape a flashlight by literally shifting the ground of their love. It is this fundamental shift — Verrückung des Grundes — that provides them with an escape route from the signifying regime governing the analytic space. At this point, I feel reminded of a Talmudic scene that has always fascinated me.

In the Babylonian Talmud, in the Tractate Berakhot (54a-b), we encounter a war scene in the hilly mountains of the Judean desert in which the Israelites flee before an enemy army, the army of the Amorites. According to the Talmudic story, the Amorites were lying in ambush, hiding in caves waiting for their chance to kill the Israelites when crossing their path. In this war scene, the mishkan, the nomadic arc, the Tabernacle, faceless and defying representation, is moving before them, zigzagging out a line of flight. How does the zigzag work? The arc, a war machine with incalculable moves, is leading a stateless gang in the desert bound by nothing but affective bonds.4 The arc levels the path of the Israelites by straightening out the landscape before them, radically unhinging territory, uprooting hills and mountains, shifting the earth with all its geological layers beneath it, creating an instantaneous escape route saving them from the Amorite enemy. Without determinate direction, like the lovers in the dream, the arc escapes the force of gravity and enters a field of celerity; its movement is a-centered and rhizomatic, being advanced by “legwork” only.5

Making use of the one spot, where the enemy is and the arc is not, the arc is turning this limit into a vast and irregular array of possible locations. From a point external to its body, from the bird’s eye view, the arc is invisible. The arc’s movement epitomizes the process of deterritorialization. It moves like the letters on an ancient page, precisely in the way the Talmud thinks: sneaking into in-betweens, in an itinerant, ambulatory move. Like the letters on the ancient page, and the lovers in the dream, the arc follows unpredictable vectors and tangents across which singularities are scattered.

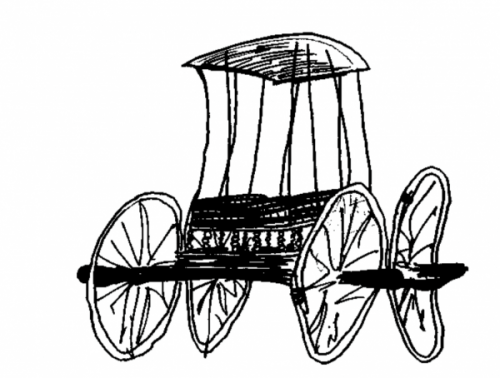

“What counts is that love itself acts like a war machine,” Deleuze and Guattari say, and that its movement is “by nature imperceptible.”6 The chapter on the war machine and the nomads’ lines of flight in Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus shows us a humorous drawing of such an ancient machine — without, however, being aware of the Talmudic story that had sneaked into the dreamer’s dream. I quote to you the Talmudic text in translation. Just as the dreamer is waking up from her dream gratefully, the rabbis, too, focus on the question of what kind of gratitude, what kind of blessing you say when you come across and see a place where you emerged safely from disaster, where your life or love was saved by errant lines of flight.

The Rabbis taught: Why should you give thanks and praise to the Creator when you see the place of the river Arnon and its valley? Because when the Israelites were about to pass through the valley of Arnon, the Amorites were lying in wait for them. They made caves and hid in them, saying: When Israel passes by we will kill them. They did not know, however, that the Ark was advancing before Israel, flattening out the hills before them. When the Ark passed their caves, the hills clung to one another and killed them, and the blood of the Amorites flowed down to the streams of Arnon. (Berakhot 54a-54b)

Those sensitive to the withdrawal of tradition past a surpassing disaster will study this passage on a desert war in a particular way. What is there to learn? Is it how to lead a brutal war in the desert? No. We have enough of that and there is nothing to learn there. Unlearning would be the more adequate response in that respect. So what is there to learn from the errant and unpredictable movement of an ancient war machine? Is it how to read, speak, act and write under the condition of an all-surround system of psycho-data-analytic surveillance? In our present situation, with both religion and love occupied by the strategic interests of all kinds of economic and psycho-political signifying regimes, the question of how to communicate under conditions of surveillance transforms. Leo Strauss’s Persecution and the Art of Writing translates into “Surveillance and the Art of Creating Shadows for One’s Loves.” The lovers in the dream are driven by both “speed and slowness,” their lines of flight are carved out by desire: they teach us how to circumvent the eye bird’s view, how to undercut central perspectives, how to contest visibility, how to insist on the lovers’ “right to opacity,” and how to remain invisible to surveillance external to the body.7

The techniques of “Talmudic thinking,” of the war machine, and the lovers’ path pertain not only to people but equally to any object, words, letters, places, and things moved by desire. The teaching of the kabbalists, “my teaching [Torah] is my constant delight and hidden pleasure,” does not distinguish between letters and lovers when it comes to the need to create shadows for one’s love.8 Letters, in the eyes of 13th century rabbinic masters, are nothing but shadows, revealing the light of creation by concealing it.8 For Scripture to be called holy, its letters and words must be illegible, as Roland Barthes says in his essay about André Masson. If we only knew how to teach this illegibility, this impenetrability in public when facing the doppelganger’s claim to legibility! The doppelganger who is treating all those letters as if they were available, rendering them into something clear and distinct! If we only knew how to defend the letters and the lovers right to opacity, and if we only knew how to hold on to the errant movement of the desert machine, its lines of flight, its shifting grounds, would we then become accomplices of Karl Abraham, saying: “Yes, surely, the Talmudic way of thinking cannot all at once have vanished from us”? Would we? And who is we? Who are we to remember the Talmud? And what is it then, “the Talmudic way of thinking”? A site-specific performance of resistance reclaiming the right to opacity for lovers and letters alike?

Yes, holiness and the sitra achra might have switched grounds without much taking note. And yes, even if we have no more than a faint memory of the Talmud, we must not forget Talmudic thinking. And yes, we may dream of yet another Sabbatean movement in which we will create lines of flight and the right to opacity and freedom for those haunted by the doppelganger’s grip.

—

This essay is a small part of a long-standing project of mine called “Wednesday Society,” including exhibitions, artistic research, poetic writing, and matters of psychoanalysis.

- This reminds me of the rabbinic teaching in Mishna Tractate Chagiga (2: 1) in which the ancient rabbis enumerate teachings that may not be taught in public, some not before three, some not before two, some not even before one, “unless he is wise and understanding from his own knowledge.” The latter two relate to matters of “the act of creation [ma’aseh bereshit]” and to the “act of the Chariot [ma’aseh merkava].” The relationship between Ezekiel’s Chariot and the lines of flight carved out by war machines and lovers alike accompanies my writing, a question much too large to be addressed in a single endeavor.

- In this context, we may want to remember the techniques developed by the medieval thinker Moses Maimonides (1135 – 1204) when facing a similar deadlock; see Leo Strauss, Persecution and the Art of Writing, Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, 1952.

- In Berlin, I know of one psychoanalyst who explores and develops a psychoanalytic setting for lovers to lie on her couch to speak, fantasize, dream, and associate freely in each other’s horizontal presence, playing by the strict protocol of Freudian/Lacanian psychoanalysis otherwise. The lovers mentioned in the dream are her only “double-couch” analysands, as far as I know. The procedure is full of surprises, pitfalls, and revelatory moments taking on the character of a rigorous and courageous experiment in both psychoanalytic discourse and psycho-poetic performance.

- “War machine” draws on the theorization of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari in A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1987), 362-366.

- Ibid., 371.

- Ibid., 278, 280.

- Ibid., 281. On contesting visibility, see Heike Behrend’s Contesting Visibility: Photographic Practices on the East African Coast (2013). On opacity, see Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation (1997). I owe this latter reference to Behrend.

- This non-literal conflation of Proverbs 8:30 with Psalm 119:77 is my own and may indicate the autoerotic arousal of the hidden pleasures of the divine. I understand that this conflation is part of a kabbalistic tradition on jouissance and desire, a theme that was developed masterfully and connected to contemporary psychoanalytic discourse by Elliot R. Wolfson in various ways. See Wolfson, Circle in the Square: Studies in the Use of Gender in Kabbalistic Symbolism (1995), 69-72, or idem, Language, Eros, Being: Kabbalistic Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination (2005), 278, 285, and more.

- See Elliot R. Wolfson, Eros, Language, Being, 2005; ibid., 206; and many more.