The International Military Tribunal for war crimes known as the Nuremberg Trials famously had a projection screen erected in the middle of the courtroom. Making film a viable form of evidence for juridical procedures merged filmic medium qualities with claims for truths. Liat Berdugo’s The Weaponized Camera in The Middle East: Videography, Aesthetics, and Politics in Israel and Palestine (Bloomsbury / I.B Tauris, 2021) offers a major contribution to the discourse of human rights and the documentary form. Following the demise of the militant image and its failure to propel an urgency of the present as part of social and national liberation movements in the 1970s, we have witnessed the rise of the terroristic image in figurative form (from videos of suicide bombers and executions, to the photos of torture at Abu Ghraib), abstract form (areal bombings and targeted assassinations’ by guided missiles with suicide cameras, as Harun Farocki called it), and an upsurge in pornographic form through the expansion of duplication and transmission technologies. As these became the dominant visual forms of mass media imagery, the documentary form began to lend itself to activist citizen journalism and to the monitoring of human rights violations.

Liat Berdugo is an artist, writer, and curator based in Oakland, CA. Her work focuses on embodiment and digitality, archive theory, and new economies. She is one half of the art collective Anxious to Make and is the co-founder of the Living Room Light Exchange, a monthly new media art series. Berdugo is also an associate professor of Art + Architecture at the University of San Francisco. Berdugo’s lucid and informed depiction and analysis in her book focuses on the work of the Camera Project (2004-2019) of B’Tselem, an Israeli human rights NGO that distributes cameras to Palestinians to monitor violations in the occupied territories. As Berdugo shows, seeing is not simply believing. Berdugo contextualizes the many layers and players in and around the specific reality of the Israeli occupation. She gives a historical analysis of the techniques, technologies and forums of visual evidence and the ways they assume the role of giving an accurate account of violent events. Berdugo is thus able to develop, out of a specific location and context, a theory of operations that can be applied to other places and circumstances as well.

In an essay Berdugo wrote for Real Life magazine while working on the manuscript for The Weaponized Camera in The Middle East, she summarized one of the book’s key points: “Visual evidence alone is not enough, because more is at stake in these conflicts than visuality. Believing precedes seeing, and seeing fails to alter belief.” Her essay suggests that the recordings of injustice may have unintended effects on viewers who actually support the violence and side with the perpetrators. This understanding informs Berdugo’s work “Shooting Back at Shooting Back” (2017), which gathers hundred of clips in which the cameras of the Palestinian B’Tselem volunteers are locked in stalemate with the cameras of Israeli settlers or soldiers — who themselves are documenting their assaults on Palestinians.

Berdugo and I have been in dialogue for many years. For our PROTOCOLS conversation, we met on Zoom and exchanged emails in a period of several weeks while traveling between California and Pennsylvania, Nevada and Israel. In the middle of our conversations, another assault on Gaza took place, and Berdugo’s book proved poignant and more urgent than ever.

—

Joshua Simon (JS): You are a visual artist based in the US. How did you get to this subject matter and what, if any, were the artistic and scholarly references you employed coming into this project?

Liat Berdugo (LB): In 2013, just after I finished an MFA focused on digital and video art, I moved to Tel Aviv for a yearlong funded residency program. It was, in a way, a return: I had lived in the state of Israel as a child, alongside my father’s large family who had emigrated there with a wave of Moroccan Jews in the 1970s. But my American mother called it quits and moved us back to Philadelphia, where I was raised in Jewish day schools, labor Zionist sleepaway camps, and other venues largely aligned with traditional American Jewish establishement values, which I had been questioning for some time.

Shortly after I moved to Tel Aviv, I heard Yoav Gross — who was then the director of B’Tselem’s Camera Project — speak at an event on photography as activism in political struggles. I was drawn to the Camera Project footage for both its political potential to oppose the Israeli occupation and for its inseparable visual and aesthetic approach to this opposition. Yoav generously allowed me to come into B’Tselem’s video department and browse its archives on days there was a free computer. At the time, I had not yet been to Ramallah, Jenin, Palestinian Hebron — Israeli law forbids all of its non-enlisted citizens, myself included, from entering area A. I went to the archives to flood myself with a vision that was not my own.

Over the years I have spent countless hours in the B’Tselem archives. I came to know the cadence of B’Tselem volunteers’ breath behind their cameras, what they sound like when they film, and what the views out their windows look like. I have come to know the physical feeling of nausea that builds in my stomach after watching video after video of eruptive atrocity or latent violence. My stomach has been fed oranges and waffle cookies by the dozens of active B’Tselem volunteers and their families who welcomed me into their living rooms to tell me about their work.

I come to this material as a researcher who is also an artist, and as such I take a distinctly visual studies approach to the material. The radical act of examining conflict through visuality means foregoing questions of what “really happened” or other such lines of inquiry that assume an underlying, essential truth that can be “re-presented” through the media. Instead, a visual studies approach means asking questions about how we see a conflict, visually — who is in the frame and who is controlling the frame? who has the right to see and be seen? who has the right to be free from surveillance? whose image is trusted? — in place of how visual media represent what “objectively” occurred.

This visual approach is especially poignant in Israel-Palestine, because the Israeli occupation has devoted considerable, national effort to a distinctly visual erasure of Palestinians: planting forests over ruins of Palestinian villages, supplanting Arab street and town names with Hebrew ones, creating separate and visually isolated roadways through the West Bank for Israeli citizens, creating an eight-meter tall concrete wall that blocks non-citizen Palestinians from sight. My approach follows in the wake of recent scholarship in visual studies that has proposed an examination of conflict through visuality, from scholars such as Ariella Azoulay, Judith Butler, Gil Hochberg, Simon Faulkner, Ruthie Ginsburg, Thomas Keenan, Adi Kuntsman, Alisa Lebow, Nicholas Mirzoeff, Sharon Sliwinski, and Rebecca Stein.

Artistically I engage with works of fiction by Palestinian and Israeli professional filmmakers, such as Elia Suleiman, Avi Mograbi, and Danielle Schwartz, as well as by Israeli choreographer Arkadi Zaides — who each construct their own fantastical or documentarian frames to comment on the visual conditions of the Israeli occupation. I have also been particularly inspired by Rabih Mroué, a Lebanese artist and scholar, and his work The Pixelated Revolution, in which he researched the recurrent trope of Syrian civilians who recorded their own deaths at the hands of the Baathist regime during the first year of the Syrian uprising. The videos feature direct eye contact between soldiers using violence to uphold the regime and civilian victims who record as an act of resistance. He categorizes this kind of video as a “double shooting”: a moment in which two different kinds of shooting — one with a gun, the other with a camera — directly face-off against one another. In the B’Tselem archives, more often I see “double shootings” where Palestinians and a Jewish Israelis simultaneously videotape each other with personal recording devices.

JS: Your video “Shooting Back at Shooting Back” (2017) uses materials from the B’Tselem archive. How did you move from using particular visual evidence for your own work to analyzing the whole archive?

LB: The move to analysing the full archive happened slowly, and over time. At first, I was really struck by hundreds of instances of dueling cameras in the archive, where a Palestinian and a Jewish Israeli simultaneously videotape each other with personal recording devices. These clips made up the material of “Shooting Back at Shooting Back” and delineated for me the ways the occupation spread into a surrogate battle between cameras. When I watched these clips of dueling cameras, I wondered: Who would look away first? What would each do with their footage? What was each hoping these images would prove? What would be the impact of Palestinian sousveillance and of the simultaneous, echoing Israeli countersurveillance? And what are the implications for me, or for any viewer — the meta-spectator in the spectral fight for visual rights in Israel–Palestine?

From that point, I began to really question the proposition of citizen videography — namely, the simplistic notion that citizen video cameras, as technological objects, cause change to a sociopolitical order because “seeing is believing.” Spectators arrive to the act of seeing with their own frames: believing precedes seeing, and therefore seeing fails to alter belief. So as I worked through the archive more fully, instead of arguing on behalf of a single and hegemonic reading of images as change-makers, I asked a host of more nuanced questions about citizen videography in Israel–Palestine. How do cameras function in the field? Do they expose? Do they produce shame in perpetrators? Do they protect the person filming? Do they produce evidence, and if so, for what forum? And, do they act as weapons, as tools to gain advantage over the other side? What followed from these questions was really a taxonomic study of countervisual citizen videography in Israel–Palestine, which is what’s contained in the book.

JS: A key reference for human rights violations within artistic circles is Forensic Architecture, whose work has set a certain look in simulating events for their investigations. How do you see their work, or the work of Bellingcat and its open source intelligence and fact-checking investigations, with regards to monitoring human rights violations?

LB: Yes, in recent years, citizen media have been elevated not as visual evidence in and of themselves, but as material for advanced “visual” or “forensic” investigations by firms like Forensic Architecture, Bellingcat, and New York Times Visual Investigations. Such investigations amalgamate many citizen-recorded videos to create a final video, which is forensically abstracted.

One way I see this abstraction is that it is both visually and theoretically opposite to B’Tselem’s approach, as well as the approaches of other human rights NGOs like Human Rights Watch or Al-Haq, which has historically focused on details as a means towards justice: dates, names, times, places, and unedited original video footage. These details are notably the kind that make good evidence inside the courtroom, as well as in the court of public opinion. B’Tselem says its raw footage shows the direct experience of the Israeli occupation in a way that cannot be ignored.

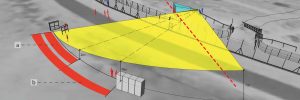

But in 2010, B’Tselem was frustrated by the lack of impact of its raw videos. So it partnered with Forensic Architecture to investigate the death of a Palestinian named Bassem Ibrahim Abu Rahma, who was protesting near the separation wall in Bil’in when an Israeli soldier fired a tear gas canister at him from a very close range, killing him. In Forensic Architecture’s recreation of the scene, Israeli soldiers are the red figures, and the Palestinian man Abu Rahma is the green figure on the other side of the separation wall. The yellow emanation out of him maps which Israeli soldier could have fired the fatal shot. What I see in this abstract rendering is its replacement of Abu Rahman’s image with an aestheticized abstraction devoid of his human attributes. Abu Rahma becomes a mere silhouette of the person he once was. In other words, he is killed once by the Israeli munition and again by abstraction.

In my opinion, the uncanniest use of abstracted bodies is in Forensic Architecture’s 2018 analysis of the killing of Luai Kahil and Amir al-Nimrah, two Palestinian teenagers who were sitting on a rooftop in Gaza when they were killed by an Israeli missile. Before they were killed, the teenagers took a selfie that became the last photograph of them alive. Forensic Architecture used this photograph, together with multiple other videos, to recreate the teenagers and the building in CG — the boys are shown in shades of whites and grays, like ghosts. But then, the boys’ selfie is reinscribed onto the rendering, aligning their likeness with their CG bodies. The resultant image vibrates between the uncanny valley of CG and the messy representations of the world of the living — a vibration that, if anything, highlights the disconnection between the two.

When actual Palestinian bodies are present in Forensic Architecture’s videos, they are often instrumentalized to synchronize multiple videos — like a clap. So the real bodies of Palestinians appear only in service to forensic analysis. I argue we should remain wary of this abstraction for two important reasons: it both homogenizes Palestinians, meaning it treats them as “all the same,” and it erases them, making them ghosts. Homogenization and erasure are two key tactics utilized by the Israeli militarized occupation to discredit and dehumanize Palestinians and continue its oppressive regime of violence.

While I do think we should be wary of forensic abstraction, I do see some utility and some good in it. Here I am thinking of the two types of injustice legal scholar Nancy Fraser defines: ordinary-political misrepresentation and metapolitical injustice. Ordinary-political misrepresentation includes injustices in which a civil society denies people the opportunity to participate in decision-making — so for instance, a citizen is denied a fair trial under law. Metapolitical injustice, on the other hand, occurs when a civil society wrongly draws the boundaries of citizenship itself. So when women were denied the right to vote, for instance, they suffered metapolitical injustice — they were not counted as full citizens. This kind of justice is higher-order: it is metapolitical. It is perpetrated by an act of misframing persons outside of the edges of the political, as if pushing them outside the boundaries of a frame, a photograph.

Throughout the course of B’Tselem’s history, it has operated under the assumption that Palestinians were victims of the first injustice — ordinary-political misrepresentation: Palestinians were denied fair access to file their grievances and to seek judicial redress in the Israeli legal system. B’Tselem sought to remedy this by the use of detailed videos as evidence in judicial litigation. But of course, this did not work. Palestinians have not been merely denied representation; they have been misframed as noncitizens. No amount of videos can make this evident: the evidence, instead, lies in the boundaries of the video frame. This concept requires generalization, abstraction, and higher-order thinking. And this is this kind of injustice that forensic abstraction has the potential to lay bare.

JS: While Forensic Architecture is developing tools for the visualization of human rights violations, even when there is no direct image of the event, they are struggling to make their products into a viable form of evidence in courts. Do you think the current International Criminal Court investigation into war crimes committed by Israel in the Palestinian territories will incorporate their work? And do you think it could bear fruit?

LB: Certainly, Forensic Architecture’s investigations angle for a juridical audience, and some of its investigations into the 2014 Gaza War — namely “The Bombing of Rafah” and “The Gaza Platform” — count audiences both of the ICC as well as the UN Independent Commission of Inquiry on the 2014 Gaza Conflict. Forensic Architecture has also published investigations pertaining to the other two main areas the ICC’s investigation will cover: Israeli settlements and the 2018-19 March of Return at the Gaza border.¹

Yet what I find interesting about the ICC investigation is how utterly long the court has spent determining whether it has jurisdiction over Israel and Palestine. Israel argues that the court lacks jurisdiction over Palestine because it is not a sovereign state. This argument somewhat tautologically denies Palestinians the right to be considered because they have already been denied civil considerations by Israel in the first place. Israel further argues that the ICC lacks jurisdiction over Israel itself, because Israel’s own courts can try soldiers who commit war crimes. Of course, Israel’s own investigations are largely considered to be whitewashed. For instance, in internal investigations into the 2008-9 Gaza War — in which almost 1400 Palestinians were killed, including over 300 minors — Israel’s Military Advocate General determined that legal standards were met in all but three cases, one of which involved the petty crime of credit card theft. So even in the case of the ICC investigations, the first hurdle for any piece of evidence — whether it is witness testimony, a map, an image, or a complex video investigation produced by Forensic Architecture — is for the proceeding itself to be recognized and deemed legitimate. The evidence cannot bear fruit if the entire case is chopped down.

I do think, however, that the work of forensic analysis is to make an appeal not merely to a court, but to a public, as is clear from its very epistemology. The word forensics derives from the Latin adjective forensis, meaning “public” or “of the forum,” from the Latin noun, forum, for which no translation into English is needed. Forensic Architecture has stated its practice is one of “establishing forums around evidence (rather than the more common procedure whereby evidence enters existing courts).”

When a video or forensic investigation is called “evidence,” this naming delineates its audience as those who can pass judgment — namely, judges and jurors. The actions of consideration, dispute, and interpretation are ones that can be taken by a wider public than that constituted by the judicial setting. As WITNESS’s Video as Evidence field guide says encouragingly, “videos captured by activists may never find their way into a courtroom … But this does not diminish the value of video to support the pursuit of accountability.” Accountability can arise within extrajudicial settings, as videos make appeals to a host of other audiences, ranging from those in quasi-judicial settings — such as the UN Human Rights Committee — to those in the general public. Thus conceived, videos can move toward a critical jurisprudence of the visual and support the rallying of an extrajudicial public empowered to watch them, take them in, and interpret their frames of view.

JS: Within the American context there is a real discussion about visual depictions of racial violence and the ways they are part of that violence. The distribution of police body camera recordings is compared to lynching postcards from a hundred years ago; the same goes to the video of Ahmaud Arbery’s execution in Georgia. At the same time, seventeen-year-old Darnella Frazier’s video documentation of the killing of George Floyd was instrumental not only in the mobilization of the BLM demonstration but also in the conviction of the Minneapolis police officer who killed him. Where do you put yourself in this spectrum of “I need to see this”/”I really don’t need to see this?”

LB: If that is the spectrum, then these days I often come down on the side of “I don’t need to see this.” As you mention, images of injustice can serve to further reinforce that injustice, as with the horrific spectacularization of lynching in America. When Mamie Till revisioned her son Emmett’s image, holding an open casket ceremony for him, she held the most public showing of a lynching that was not intended for white supremacy but for Black justice. But the question that remains for the images of Ahmaud Arbery, of George Floyd, and countless other Black and brown victims murdered by the police, was posed most purely by Ismail Muhammad: “Can you look at these images and honor black life?” I think the answer is no far more often than yes.

But I would expand your spectrum. It’s not just “I need to see this”/”I don’t need to see this.” There’s a third option: “Whether or not I see this image, seeing is not enough.” By this I mean that images do not stake out a sufficient relationship to justice, to social change. The civic potential of images that Ariella Azoulay lays out in her celebrated book, The Civil Contract of Photography, requires an active spectator, which precludes many of us who change the channel, flip between browser tabs, or look away from photographs and videos. Carolyn Dean has written extensively on the gap between “representation and responsibility” that opened after images of the Holocaust’s horrific concentration camps circulated in 1945. Viewers bore witness to images of atrocity but failed to understand and to act. In Israel–Palestine, images of Israeli state violence or of Palestinian suffering have yet to deconstruct the apparatuses of control and domination contained in the occupation that causes them.

So what is needed is not simply better cameras, more cameras, or higher-res cameras. Likewise, what is needed is not simply a better way to validate the “truth” of images, or merely a wider distribution network for visual recordings. Of course, none of these things would hurt efforts to dismantle racial violence or the Israeli occupation. But instead we must come to accept that images do not speak for themselves, in large part, because what one can see in an image is already a matter of a set of power relations that structure vision, visibility, and visuality. In other words, while images do have what Judith Butler calls a “transitive function,” meaning that they act on viewers to directly impact judgement, the ways in which images act are constantly up for debate, interpretation, and interpellation. It is essential that images not be blocked from the sphere of appearances, which is also the sphere of the political. But “it would be a mistake to think that we only need to find the right and true images, and that a certain reality will then be conveyed,” as Butler put it.

While my third option — “Whether or not I see this image, seeing is not enough” – is perhaps pessimistic, it yields that the meaning of an image, as well as a spectator’s affective response to it, is not fixed in nor overdetermined by the image. Instead, that meaning is determined by the framing of an image, which is iterative and volatile and which dominant regimes use their power to control. But a regime’s domination over the frame will change depending on who holds power. In the United States today, images of lynchings that used to circulate as souvenirs celebrating white supremacy and denying Black grievability have been formally memorialized in a national memorial and museum dedicated to the anti-Black terror of lynching. But in Israel, the prevailing sociopolitical order does not yet allow for Palestinian grievability. In the summer of 2014, after Israeli incursions in Gaza resulted in the death of over 150 Palestinian children, the Israel Broadcast Authority Radio refused to air a B’Tselem paid advertisement that read out the names of each child. The Israeli Supreme Court upheld the censorship of Palestinian death from Jewish Israeli ears. The Israeli regime is still flexing its power to control the frame of its now six-decade-long occupation.

JS: The Jan. 6 attack on the US Capitol amounted to individual criminal charges, playing into a broader depoliticization of white supremacy in the US. One limitation of the humanitarian discourse is its insistence on individual rights, which for Israel, as an occupier, plays into the politicide of the Palestinians, for example. In that respect, humanitarian discourse depoliticizes the crimes and the subjects, denying them the collectivity for which they are assaulted and in whose name they are acting. Do you see a correlation between the specificities of the documentary monitoring of human rights violations and the humanitarian discourse at large?

LB: Yes, the question of individual rights is an important one, as human rights organizations’ focus on individual cases and details misses the point. I believe that B’Tselem has undergone a monumental shift away from individual rights since its founding in 1989. Historically, the organization sought to secure human rights for Palestinians through the amassment of details of what it assumed to be a temporary occupation of Palestinian territories. The organization meticulously and assiduously documents names, dates, times, locations, eyewitness testimonies, photographs, and unedited original video footage through its Camera Project.

But in 2016, after finding that Israeli military investigations into infractions perpetrated by its soldiers resulted in near impunity for its troops, B’Tselem decided to cease cooperation with Israeli military investigations in a deliberate move away from the pursuit of individual rights. B’Tselem felt that the outcome of its participation in the Israeli military’s criminal justice system served as the occupation’s “fig leaf,” meaning it concealed an embarrassment that Israeli society had with its own military occupation. Within Jewish Israeli society, radical leftists have often argued that humanitarian activism bolsters Israeli militarism rather than weakening it. B’Tselem ultimately reached the same conclusion: that it must stop cooperating with the State of Israel and what it calls its “fake justice” system in order to further its anti-occupation and humanitarian goals.

Just this year, B’Tselem released a position paper formally calling the Israeli regime an apartheid. I read this move as one more effort to reinstate collectivity to Palestinians, in a public recognition of generalized, systemic, and structural inequalities of the occupation as ones that individual rights cannot remedy. Instead of seeking successful prosecution of low-level soldiers for violating orders, B’Tselem’s new policy asks for a much larger, more general solution to the entirety of the Israeli occupation. That solution, of course, is to end it.

Talk of individual rights in this context reminds me of the 2008 film, Z32, by Israeli director Avi Mograbi. The film is a musical-documentary-tragedy that follows an army veteran of an elite IDF unit who committed a revenge killing of a Palestinian policeman. Mograbi promises the veteran that his identity will be concealed, but he struggles to do so on film while still showing his eyes and mouth — facial features that convey the emotionality of testimony to viewers. Mograbi ends up enlisting the aid of three-dimensionally rendered computer graphics to supplant an entirely new face onto the soldier in post-production. Even this final “face” is not perfect: it is programmed as the topmost layer, resting above the original footage. Therefore, everything that might normally be visible in front of a face — such as a hand scratching the cheek, a cigarette being brought to the lips — becomes uncannily suppressed in space, appearing underneath this digital mask. The digital mask otherwise looks quite realistic, and for minutes at a time a viewer can forget it’s just a mask.

But the moments where we see it as a mask are essential — they do the important work of directing our attention away from the soldier’s individual identity as a specific person, gesturing instead toward a generalized IDF combat veteran. The mask asks: could this soldier have been anyone? It at once conceals and abstracts, asking us not to merely consider the guilt or absolution of the army veteran himself but of the entire military apparatus that sustains its violent occupation of the Palestinian territories.

JS: The recent clashes in Israel, although somewhat familiar (disproportionate firepower, the joy of fascism, liberal righteousness, messianic and technological self-realization), seem to lead toward a civil war with possibly genocidal potential. How do you see these developments?

LB: I see this as more of the same settler-colonial violence, and indeed the new civil dimension shows how the values of a settler-colonial regime are ingested and thereafter enacted by its citizens. Even before this latest violence, the State of Israel was using the coronavirus pandemic to advance its settler-colonial regime: it blocked human rights work in the Occupied Territories, but not human rights abuses; it forced Palestinians with pending permit requests to download a smartphone application that surveils them, granting the Israeli security services access to their location data, contacts, camera, notifications, and file downloads; and its settlers waged campaigns of increased settler violence, including the forcible seizure of two B’Tselem cameras and the stealing of a B’Tselem security camera mounted in Hebron.

Because I take a visual studies approach, I have been paying careful attention to the images produced and recirculated in this latest violence. I was struck by the front page of Israel’s left-leaning paper Haaretz, which published headshots of the children killed by Israel’s offensive under the headline, “67 children who were killed in Gaza: This is the price of war.” While the headline used passive voice (the children “were killed”, not “Israel killed them”), the act of publishing these images marked a significant change in the status of Palestinian life as publicly grievable in Israeli circles — in stark contrast to 2014, when the Israeli Supreme court upheld the censorship of B’Tselem’s paid ad to read out the names of the Palestinian children killed in that year’s Gaza war.

Also, over the course of this last assault on Gaza, I began a rather dark obsession with the Twitterverse of open source intelligence (OSINT) analysts who focus on gathering military intelligence on Palestinian militant groups by analyzing photographs, such as the work of Fabian Hinz or BlueSauron, among others. Like Forensic Architecture and Bellingcat, these independent analysts pride themselves on uncovering information by amalgamating trove of photographic sources in order to reveal information that is “hiding in plain sight” — that is, to make it legible to the public, through the use of visual annotations. BlueSauron posted an extensive thread creating a typology of missiles through the analysis of video stills, propaganda images, military parades, and weapons modelling to identify 18 missiles used by the Al-Qassam Brigades, 22 by the Al-Quds Brigades, 15 by the Al-Nasser Salah Al-Deen Brigades, and 15 by Al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades.

What I find interesting about the work of these OSINTs is that they use the language of visual forensics when it is often completely unnecessary. For instance, BlueSaron will annotate its images by highlighting the missile in question in a yellow rectangle, though the missile is the only munition present in the photograph. To me, these gratuitous annotations betray a belief that the missile would be otherwise indiscernible to a Western layperson’s eye — even while images of Israel’s Iron Dome, for instance, are almost never annotated and circulate widely without visual explanation.

Likewise, I have been following the images produced by Israeli veterans under the hashtag #standwithisrael — and especially the TikTok videos of the Alpha Gun Angels (AGA), a fascinating/horrifying group of female IDF combat veterans turned gun influencers and Instagram celebrities. The group’s founder, Orin Julie, released a video in which she is sheepishly and demurely wearing a baby-pink dress; but then the video jump cuts to her in IDF fatigues, looking bold, empowered, and finally in her body. In the video’s caption — “Cus I’m always happier when I protect my country” — she locates the feminine power her dress did not allow inside the IDF’s militaristic capacity to “protect.” She taps into a long, patriarchal history of women as those who “hold down the fort” at home, defending it (and often the children inside it) from the outside world. As such, she mobilizes the image of her femininity to deny the offensive and disproportionate nature of the Israeli violence, instead pitching it as merely defensive.

I also followed another AGA member, Natalia Fadeev, who posted a TikTok video in which she poses sexually in her IDF fatigues, asking, “…now tell me, do I look like I could harm innocent civilians?” Central to Fadeev’s video is once again the question of appearances. She does not ask, “Am I the kind of person who could harm innocent civilians,” but instead, “Do I look like the kind of person who could harm innocent civilians.” I understand this move in terms of Jacques Ranciere’s conception of politics as a space of the sensible, as well as Hannah Arendt’s argument that “Being and Appearing coincide” in politics — that is, politics is intrinsically tied to visuality and cannot be guided by an invisible or unseeable force — to show that what is visible, and indeed what is viewable, is already a matter of politics.

- See “Conquer and Divide” on the former, and “The Killing of Rouzan Al-Najjar” on the latter.