[Image description: Screenshot of Reading Scholem in Constellation (RSIC) virtual meeting. The faces of eight participants are shown in individual boxes—three stacked onto three stacked onto two—each posing in the middle of attention and thought.]

A few weeks ago, my grandmother revealed a puzzling discovery. Upon cleaning her kitchen, she had found a scrap of paper with a name on it. “Do you know who Gershom Scholem is?” she asked. I found myself imagining this paper shifting across her counter, the dense cursive dribbled with tea. It confronts the stares of a thousand framed baby pictures, curls around the edges, and then finally falls to the floor with a sigh. Perhaps she wrote the name down when I mentioned that I am starting a reading group about Scholem, but I like to think it just appeared there one day, adorned with a question mark.

Gershom Scholem (1897-1982) was a German-Jewish historian, philosopher, and philologist best known for establishing the study of Kabbalah as an academic discipline. Although he is a major figure in Jewish thought and has experienced renewed popularity, Scholem is still mainly read in the contexts of Jewish Studies, theology, and literature.

The Reading Scholem in Constellation (RSIC) reading group took place from October to November 2020 at Hopscotch Reading Room, Berlin. It sought to place Scholem’s early writings on lament in dialogue with other cultural contexts, histories, crises, and tensions. It was an attempt to imagine Scholem in new contexts, springing from unexpected and contingent encounters with writings from Sara Ahmed, Fred Moten, and Jalal Toufic. Resulting conversations departed from Scholem’s abstract yet evocative idea of lament and traced the edges of a year of sickness, death, racial violence, social and emotional isolation, revolt, and exhaustion. The group and its conversations are still ongoing and our collective dialogue activates questions such as: can Scholem’s thoughts resonate in the present through critical re-reading? Can lament cry out against linear, teleological ideas often positioned as universal, such as language, mourning, or healing? Can the practice of mourning actively change that which is mourned?

Far too alienated

Scholem first wrote about lament in his diary while in his tender early twenties. From 1917-1919, he wrote a series of translations, commentaries, and reflections, most of which remained unpublished in his lifetime. These writings encompassed Hebrew to German translations of chapter three of Job (“Job’s Lament”), chapter 19 of Ezekiel (“A Lamentation for Israel’s Lost Princes”) and Rabbi Meir of Rothenberg’s lament (“A Medieval Lament”), along with commentaries on these translations — including “On Lament and Lamentation,” an introduction to Scholem’s translation of the biblical Book of Lamentations.¹

Speculative/theoretical texts such as “On Jonah and the Concept of Justice,” which addresses the theme of divine punishment, are also a part of this output. All of the original Hebrew laments are poetic and emotional — Job’s lament calls out: “why did I not emerge dead from the womb / exit the womb and expire” (3:10).² Scholem’s commentaries often voice abstract theological, theoretical, and linguistic considerations that arise from these contexts; in “On Lament and Lamentation” (1917), he declares that the lament’s “entire existence is based on a revolution of silence.”

Anthony David Skinner, translator of parts of Scholem’s diaries, describes a broader context of youthful discontent in this period. Early 1900s Berlin, the capital of the monarchical Imperial State of Germany since unification in 1871, chafed under the strict hierarchical structures derivative of the Prussian nobility and upheld strongly by the middle class. Many young members of this middle class sought more personal freedom and rebelled against what they considered the hypocritical, bourgeois values of the previous generation. Scholem likewise clashed with his parents; he felt their secular-Jewish, middle class lifestyle pandered to rational and commercial values. His lonely diary entries from this period deal with what was to become a lifelong preoccupation: the idea that the spirit of Jewish tradition had been lost in secular, assimilated German-Jewish milieus.

One night, I texted with RSIC participant Nathan French, an MA student at Humboldt University:

Me: I’m reading Scholem’s diaries in bed again.

He’s so narcissistic at such a young age

Nathan: incredible

we all are I guess, no?

Me: True, but I’m pretty sure I didn’t think I was the messiah when I was 16³

Nathan: same. I’m far too alienated for those kinds of ideas lol

I thought about how Scholem’s early writings were a youthful attempt to make sense of the world and actively change history. His interest in chaotic and irrational mysticism had not yet crystallized in his decision to study Kabbalah, but it underlined his belief that Zionism might revitalize a deadened Judaism. In a 1915 diary entry, he declares, “Our guiding principle is revolution! Revolution everywhere! … Above all, we want to revolutionize Judaism. We want to revolutionize Zionism and preach anarchism and freedom from all authority.” Scholem briefly considered socialism, but did not belong to an organized political party. He never defined his anarchism, but, while anarchy typically denotes a society without hierarchical authority, his definition of anarchy seems to be a creative force for a spiritual renewal of Judaism that reinvigorates its “inner essence.” Anarchy in this sense calls for freedom from authority while remaining vague about how spiritual renewal would actually take place without it. Particularly, it decries secularized German Judaism and the political realization of a national Jewish state, but also a world mired in rational, exoteric concerns and blind to a shimmering utopia just around the corner.

What would Scholem search for today? I thought of Karen Bray’s Grave Attending (2019), a book of multidisciplinary political theology rooted in a sense of impending global crisis and the moods that lay behind it. She describes lament as conversely hopeful and despairing action rising from deep grief, existential anguish activated by real political concerns. Deep grief, in particular, rings out against neoliberalism as an exclusionary system of redemption. Bray posits that neoliberalism is spiritually based on the promise of redemption for those considered “good investments” and withholds this possibility for those too sick, moody, unproductive, or racially other to be “saved.” While Bray posits strength in the moody refusal of neoliberal redemption, Scholem seems to question whether this mystical moodiness can remake the world itself.

In Lina Baruch and Paula Schwebel’s introduction to Lament in Jewish Thought, they point to Itta Shedletzky’s idea that Scholem’s writings on lament can be seen as “a work of mourning” over a lost Judaism. But this implies some original Judaism to lose in the first place. I am drawn more towards another possibility, via Scholem scholar Daniel Weidner, that Scholem’s lament uses “inscription” via translation, writing, and commentary in an attempt to productively thwart the steady degradation of Jewish tradition. In Gershom Scholem: Politisches, Esoterisches und historiographisches Schreiben (2003), Weidner argues that Scholem does not only write alongside tradition but actively attempts to replicate its form and thus modify its content. This second idea points to Scholem’s use of lament to create anew what he felt had been lost.

I am drawn more towards another possibility, that Scholem’s lament uses “inscription” via translation, writing, and commentary in an attempt to productively thwart the steady degradation of Jewish tradition.

Eikhah

A main text in Scholem’s writings on lament is “Über Klage und Klaglied” (On Lament and Lamentation), an introduction to Scholem’s translation of the biblical Book of Lamentations. The Hebrew word אֵיכָה (eikhah, translated as “how”) rhetorically structures the Book of Lamentations and connects Scholem’s translations of historical laments to his introduction’s theoretical preoccupation with the gap between divine and human language. This unanswerable “how” begins three of the four chapters of Lamentations — whose original name in Hebrew is in fact “Eikhah” — a long poetic lament assumed to be written in response to the destruction of the first Jewish Temple by the Babylonians in 536 BCE.

Galit Hasan-Rokem describes how the Book of Lamentations is divided into chapters based on the lamenters. It first describes a female city — Jerusalem — that laments in first person; then her and the city’s elders, virgins, and children; suddenly a male lamenter; and lastly, an unknown entity who accepts and justifies God’s actions. It starts out graphic: Jerusalem and a woman shouting “I!” blur together, weep, spread hands, describe splitting bowels and wombs. There are less gestures as the poem moves from the shouting woman to the defender of God. Hasan-Rokem argues that while later characters mostly speak, the woman or women from the beginning wordlessly tear themselves, or herself, apart. She posits that Scholem’s active ignoring of these aspects is part of “his methodological denial, indeed rejection, of the performative, embedded and contextual elements of the texts he studied” in favor of overarching myth.

“On Lament” not only doesn’t address the context of Lamentations but also does not mention or discuss the biblical translation it supposedly introduces at all. Rather, it favors dense speculations about lament as a wordless, pre-linguistic essence only answerable by revelation. Within the span of a few dense pages, it poses riddle-like, authoritative statements on the theo-linguistic nature of lament, such as: “This language reveals nothing, because the being that reveals itself in it has no content (and for that reason one can also say that it reveals everything) and conceals nothing, because its entire existence is based on a revolution of silence.” Akin to the use of “anarchy” in the aforementioned diary entries, “revolution” is also left ambiguous, likewise creating a broad (albeit poetic and evocative) myth that leaves the details sketchy. In this schema, Hasan-Rokem seems to suggest that even in Scholem’s endeavor to reinsert the irrational, moody, and chaotic back into a scientific Judaism, his lack of contextual detail results in broad, authoritative statements that ended up replicating this structure by producing yet another History.

Silence

Reading Scholem in Constellation took place in a year dominated by extremes, which, as an American ex-pat living in Berlin, I traced between the US and Germany. The violent deaths of so many Black people — Breonna Taylor, Amaud Arbery, Tony McDade, Elijah Mcclain, George Floyd and many more — and the resulting uprisings reverberated on an international scale. The popular Die Zeit ran an issue on “Amerikas Sünde” (America’s Sins); a few months later, news broke of a far-right network within the German police and military. Corona raged and Germany went into lockdown; deaths in the US piled up. The Moria refugee camp in the Greek island of Lesbos burned and Germany roiled with debates over whether to open its borders. The 2020 US election campaign overflowed with the propagation of and clashes against misinformation and blatant sexism, racism, and xenophobia, within an ever-more polarized climate in which “left melancholia” often felt like left paralysis.

About twenty people showed up to the first meeting: a mix of artists, poets, scholars, translators, and philosophy students. Due to COVID restrictions, we met directly outside Hopscotch Reading Room and read “On Lament and Lamentation” in the damp cold. We spoke about how, traditionally, Jewish laments enact mourning by linking back to the now-mythic destruction of Jerusalem. Poetry, prose, prayers, and holidays often reference this tragedy as they speak about other disasters. It was clear that Scholem’s idea of lament rejected both this tradition and historical specificity. What exactly, then, had he created?

“On Lament,” originally written in response to Walter Benjamin’s “On Language as Such and the Language of Man” (1916), describes lament as a unique linguistic form. It paradoxically both expresses an object of mourning and destroys it in the attempted communication process. In this violence, signification collapses, and the lament is left without content, reminiscent of a wordless wail. This chasm recalls the idea of the gap between divine revelation and the failure of its reception in human language. In this schema, Scholem posits revelation and lament as opposites, thus seeming to say that lament is only answerable by a revelation from God, and raising the question of what to do in seemingly futile anticipation of such a reply.

Before and after the group meeting, I sent everyone a link to philosopher Illit Ferber’s recent talk Language Failing: The Reach of Lament. She speaks of Scholem’s lament as defying the laws of language itself. Ferber argues that the idea of language is based on the positive assumption that something can and will be communicated, while the wordless lament rejects this task. This refusal to communicate can be seen as a broader condition of the world. It asks an unanswerable how: how can the universe be in such a condition? Just as Scholem contrasts lament as open-ended and mourning as an object that is to be eventually overcome or destroyed, Ferber emphasizes that the lament stubbornly refuses to conclude.

Participant Wendy K. Shaw, Islamic art scholar and professor, paralleled sacred language with God, word, and creation in the Arabic غرب (gh-r-b). The root غرب is “related to the word for strange, but also for West, so we might think of it as estrangement, which is the idea that we are always already at a loss because we are cut away from our Divine home. Thus, nowhere on Earth can be a true home, and we must make each place on earth a home.” Language is both inseparable from God but also part of a necessary exile that occurs when the human is separated from the divine. غرب is also similar to the Hebrew root גור (g-oo-r), which means “to dwell/to be a stranger.” In Stranger in a Strange Land, George Prochnik poetically suggests that when Scholem moved to Palestine and changed his name from Gerhard to Gershom (translated as “a stranger there”), this sense of estrangement was cemented.4

This linguistic exile also resonates with real world violence. Participant Tracy Fuad, a poet, related how, “last fall, when the US pulled its troops out of Rojava and abandoned the Kurds and Turkey started bombing civilians, there was a woman who was filmed holding the corpse of her child and screaming ‘Why don’t you see us as humans? Is it because we speak Kurdish?’”

Many during the group meeting asked about how Scholem’s political views were embedded in this schema. While Scholem was a committed Zionist, his vision was based on an esoteric spiritual renewal rooted in Hebrew revival. He arrived in Palestine in 1923 and met a national political movement increasingly entrenched in, and dragging his beloved Hebrew into, more and more violence. He joined Brit Shalom, a group of European Jewish immigrants that agitated for a bi-national Arab-Jewish state — but eventually this group and his efforts faded. While he occasionally spoke out (against the 1967 war, for example), he reconciled himself to Israel as a state and to an entirely other Zionism.5 In this sense, the strange גור/غرب, perhaps a moaning wail, can be seen as a disenchanted sonic echo, something that haunts those searching for wholeness in lands, languages, ideologies, and the divine.

The Justice of a Lament in Three Parts

The themes of Eikhah and Estrangement tied in to our second reading, “On Jonah and the Concept of Justice,” which is rooted in the biblical story of Jonah. God tells Jonah to warn the sinful city of Nineveh to repent. He refuses, runs away, gets swallowed by a large fish, and then promises to warn Nineveh. Surprisingly, the people of the city repent. But when God spares them, Jonah is upset. “Jonah is childish,” Scholem argues (italics his), because he doesn’t understand how divine justice works. In this world, no definite divine action can be enacted. Thus, the divine arc of justice is always delayed in the anticipation of a coming messianic future in which the decision will finally take place. Leon Gelberg, a philosophy student, described the suspended temporal arc of delayed justice, masked (like all of us), fingers winking with silver rings.

One can almost imagine Scholem smirking as he declares Jonah childish. In this sense, childish means refusing to accept the prevailing state of the world because the child doesn’t fully understand the way it works. Just as lament seems only answerable by God, so too only the divine can enact justice. In “Jonah,” eikhah is a means of questioning why and how God doles out justice. There’s a sense of failure to reach a designated point, but also a lack of desire to get there. Akin to the previous discussion of the strange and exiled lament, expectations of a satisfying ending are upended: justice never arrives, but Jonah also resists in the face of none other than God.

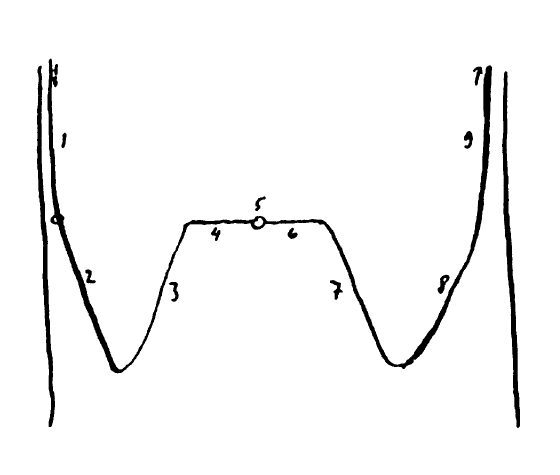

Poet Seda Mimaroglu pointed out that Scholem’s justice graph looks like a pair of sagging breasts.

We couldn’t help but think of how the young Scholem had so strongly willed not only a different Judaism but also a different world, only to eventually meet disenchantment. Cellist and composer Lucy Railton described how, sequestered inside during corona, she had created a musical piece called Lament in Three Parts. She played it for us — seemingly hoarse grating pressed up against deep notes, reminiscent of an alienated dialogue.

[Image description: Hand-drawn graph, with a line—as if drawn somewhat carelessly—forming, incidentally, as Seda writes, “a pair of sagging breasts.” The line, in its movement, is numbered one through ten in Arabic numerals, beginning at the top left of the image and ending at the top right.]

Just Enough Alienation

In “Killing Joy: Feminism and the History of Happiness” (2010), Sara Ahmed notes that intellectual histories of happiness depict this term as a harbinger of meaning and purpose. She questions the linear, teleological nature of this desire and then contrasts it with alternative feminist histories. Many such examples from literary sources, such as Virginia Woolf’s 1925 Mrs. Dalloway, question this history by “suspending belief that happiness is a good thing.” Ahmed then explores the political dimension of the demand to be happy and proposes that we instead read the history of unhappiness via the figure of the wretch, “a stranger, exile or banished person.” Ahmed upholds exile/the stranger/unhappiness as purposeful sites of frustrating the desire for and creation of happiness. This refusal resonated with Wendy and George’s ideas of the exiled stranger who defies the conclusion of a promised land, redemption, or goal.

By the time the next meeting had been scheduled, the government had issued nation-wide orders that all restaurants and cultural events close for November. We moved online. Shulamit Bruckstein, director of House of Taswir, loved Ahmed’s emphasis on the “hap” in happiness as etymologically related to “gap.”6 While normative ideas of happiness emphasize it as a destination at the end of a linear trajectory, “hap” disturbs this. Ahmed argues for the embrace of alienation not as a form of negativity, but rather of reclaiming this hap and refusing to conform to some specific goal of happiness. She calls this figure that embraces alienation the “killjoy,” reclaiming a negative word and positioning it as a site for community. In this sense, alienation is the site of experiencing genuine rather than mandated joy.

Gigi Leung, a data scientist, found the text comforting, while Migle Bareikyte, a media studies scholar, brought up the optimistic complaint. We discussed how this felt like a rebuke of neoliberalism connected to Lauren Berlant’s idea of “cruel optimism.” Neoliberalism sets one up for goal-oriented success that is always on the horizon: work ever more hours, dissolve the border between work/life and eventually burn out and break down, only to successfully overcome this fatigue in order to work more. Tracy wondered what this meant amidst the forthcoming corona lockdown.

On the one hand, both the killjoy and the lament refuse to tread a defined path and stubbornly refuse to be happy by deriving strength from that which has been historically suppressed. But this last point brings up certain ambiguities. While Scholem claimed that he was speaking on behalf of a Judaism lost to the harsh forces of modernity, it is questionable what tradition he actually revived with his abstract, ahistorical, linguistic speculations on lament. Who gets to speak for an entire cultural tradition? Hasen-Rokem pointed out earlier that Scholem suppressed certain voices in his conceptualizations, but perhaps also worth noting is that Scholem did maintain a goal: to modify history. Ahmed was also powerful in this discussion because her work argues for reading of thinkers beyond mere ontology: that is, in their situated contexts, replete with problematic personal histories and political aims. In this sense, Scholem’s lament was inseparable from Scholem himself. Thus, the group meditated, are we interested in lament as a form or in listening to who laments?

Meeting four: discussing Sara Ahmed’s “Feminism and the History of Happiness”. From the top and left to right of each line: Shulamit Bruckstein, Tracy Fuad, Gigi Leung, Migle Bareikyte, Rebecca Layton, Claire August, Nathan French, my empty plinth and I.

Moaning

A few days before our second to last meeting, Wendy sent me a message: “You are planning an online discussion of Lament on Election Day… I see you are preparing.” I responded, “While there are always things to lament, I hope the day will not prove too worthy of that discussion.”

Fred Moten’s “Black Mo’nin’”(2003) starts from the infamous photograph of Black teenager Emmett Louis Till’s brutalized face. In August 1955, Till was visiting relatives in Mississippi when he stopped in a convenience store and allegedly whistled at or flirted with a white woman. A few days later, her relatives brutally lynched him. His mother decided to publish the image of his mutilated body in the magazine Jet. Even though Black people widely and regularly lived with organized terror and murder, this particular image was so gruesome that its distribution encouraged renewed support for the movement against segregation and its constituent violence.7 Moten argues that this picture can be seen as a site of “black mo’nin,” an audible sound arising from the picture, a “sound component to the massive implications of this image.”

Moten describes this noise as a broken speech that haunts the picture and sits in a lineage of sounds that refuse to be neutralized. Migle described the text as rhythmic and the rest of us all wondered about the balance created by this rhythm. We noted the creaking, moaning, screaming, and wailing pervading the text. I was reminded of Scholem’s concept of divine justice, an infinitely deferred action only enactable by God. The broken noises seemed to haunt the impasse in which humans, perhaps incontent with their imperfect societal laws, are nevertheless supposed to wait for divine decision. In Moten’s description of Emmett Till’s face, the line between these two spheres of justice seems to quiver. “Emmett Till’s face is seen, was shone, shone… As if his face were the truth’s condition of possibility, it was opened and revealed. As if revealing his face would open up the revelation of a fundamental truth… as if revealing the face would deconstruct justice or deconstruct deconstruction or deconstruct death.” In this terrible shattering, the face shines to haunt, to break things down. In this shattering, it seems (scheint in German, pronounced like “shine”) that images waver (whistle?).

Throughout the text, Moten argues that poststructuralist Roland Barthes’ idea of the de-constructed subject/viewer is a means of imposing his own (white, male) view as universal. I thought of Scholem’s construction of Kabbalah as an academic discipline, while Mimi Howard, a PhD student in post-war German political thought, wondered whether “theories of lament or moaning always have some kind of originary (particular) event that they pay homage to in their repetition.8 “Is that repetition accessible,” she questioned, “only to parties who are historically, culturally, or otherwise tethered to the originary/exemplary event? Or do they speak to precisely the ‘impossibility of universality’ Moten is trying to get at, and then also overturn?” Moten creates a tension between absolutes: the historical depiction of cultural practices such as seeing/mourning as universal versus the denial of subjectivity via the impossibility of seeing/mourning.

A photograph can be replicated into infinity, meaning that we both no longer need to visit the sacred object originally photographed and that we supposedly experience an imperfect version of the image via its copy.9 Perhaps “mon’in” has been whistling through the cracks of these two poles, shining and broken. Like the lament, a condition of a world that refuses such extremes because it is fragmented from the start. Moten describes his aunt’s funeral as a “condition of impossibility of universal language, condition of possibility of a universal language, burying my auntie at morning time, where mourning renders moaning wordless… Sister Rosie Lee Seals mo’ned. New Word, new world.”

Eikhah

The killjoy, the lament, and the moan… sounds like the beginning of a bad joke. But they don’t walk into a bar, as some of them have mouths but no bodies, and one not even that, but just—. They laugh about how all the other sounds are out searching for justice, but, honestly, moan and killjoy are suspicious of lament: “an enormous abyss hides away in the austerity of form.”10 They know, they know, they’re all in it together, all this refusal of language/the future/purpose/completion—but.11

Well, it often feels like moan, killjoy, and lament can agree on resistance as such and sometimes on what to mourn, but they can’t help but wonder how to make community, solidarity, out of this sound. It all mostly brings up questions. And to every question, yet another question, and a chain of questions rings out in the cold November air.12