As an artist descended from crypto-Jews—the Catholic converts who secretly practiced Judaism in the wake of the Spanish expulsion and inquisition—I created In Thy Tent I Dwell because I could no longer create art without addressing my ancestors’ narratives, which had for centuries been silenced by persecution, fear, and the fogginess of long stretches of space and time. This installation, which captures my convoluted and non-linear crypto-Jewish narrative, also declares that our affiliation to the Gente da Nação, Jews of the Portuguese nation, will not be displayed with spiritual inadequacy, as a stain in a Purity of Blood Certificate¹ or in a confession at an auto-de-fé. Instead, our history, at last, will be spoken by our own mouths.

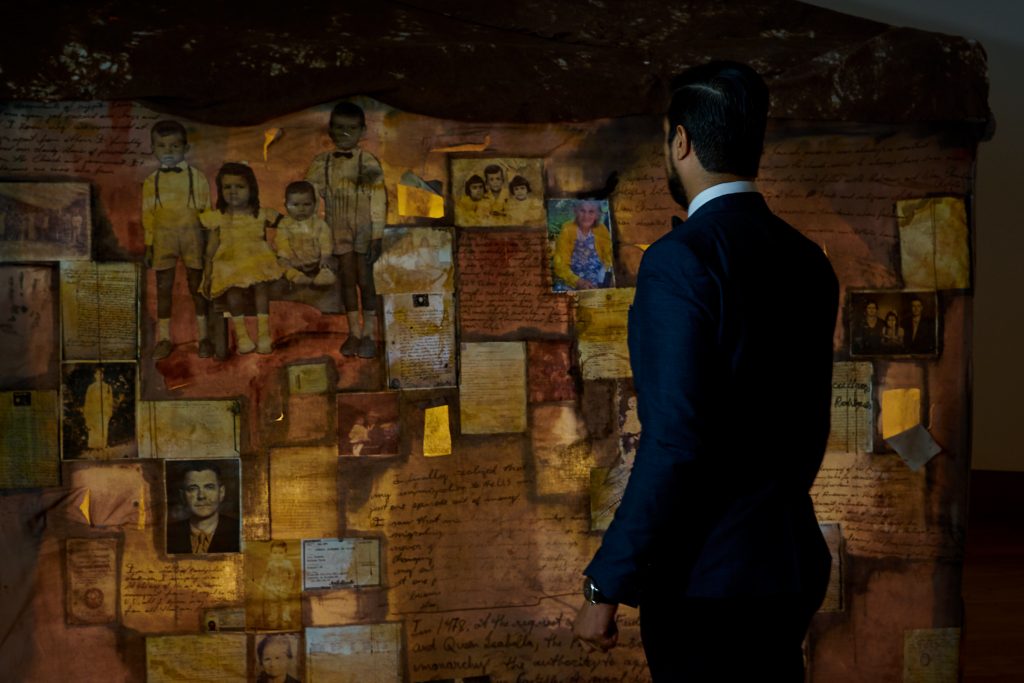

In Thy Tent I Dwell is a multi-sensory experience that emerged from the painting, threading, writing, and layering of photographs, birth certificates, inquisitional archives, DNA exams, and immigration documents onto a tent-like structure. The outside surface of the installation was 10′ x 10′ x 10′ in size, and the interior of the tent became the creative depiction of the quarantine room where my Andalusian ancestors stayed when they first arrived in Brazil in 1909. Other earlier branches of my family had arrived in Brazil in the 16th and 17th centuries, and together they would contribute to the making of the tent. Inside, there was a small fan, a nightstand, a glass of water, a briefcase, bags of spices (from the Mediterranean including North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula and South America) hanging from the ceiling, and a small bed in the middle surrounded by five lamps. Our family lore was our greatest protection while in exile. The fabric of our tent was flimsy, but its malleability was symbolic of the mightiness of the teachings of our fathers and mothers. After all, we were not lost Jews; we were simply hidden Jews.

The installation was, therefore, a visual representation of my ancestors’ central teaching: Dum Spiro, Spero: “While I Breathe, I Live.” As it is written in Sefer Eleh ha’Devarim, the fifth book of the Torah, “…I have set before you life and death, the blessing and the curse. Therefore choose life, so that you and your children may live” (30:19).

Crypto-Jewish communities are full of slightly differing versions of Jewish ritual, often with a degree of distortion from the original halakha (Jewish law). Like most of my work—and unlike the male-exclusive model of transmission presented in rabbinic texts—the tent emphasizes a vociferous female presence whose matriarchs gave authoritative guidance on the practice of Jewish ritual.

My mother’s grandmother, Dona Elisa de Oliveira, had 22 children and lived past the age of 105. Until her 90s, Elisa ruled the family in a strict manner, making sure her daughters and granddaughters were especially vigilant about the laws of niddah—the laws governing the ritual purity and impurity of women. She taught her daughters the days of separation necessary between a husband and a wife after childbearing, as well as the ritual of mikvah-immersion—although the rabbinically mandated seven-day period of separation after menstruation was absent. Elisa’s rulings could adapt to restrictions of the moment. While living in the country, her daughters were taught to go to the river after their menstrual periods, but those who had relocated to larger cities without natural bodies of water were taught to go outside and take a rain shower on the first rain after their periods; only then could they have marital relations. While such a practice is not halakhicly valid, the fragmented mikvah ritual nonetheless reveals a desire for the ritual purity itself.

As with Dona Elisa, evidence from Inquisitional archives has shown that crypto-Jewish families received most of their teachings from female figures. For instance, historian Renée Levine Melammed notes in Heretics or Daughters of Israel (1999) that crypto-Jewish women would “subvert the teachings of the Church and risk prison or death to provide for the Jewish continuity of their families.” One could suggest that such is an important crypto-Jewish precept: to live Jewishly, though implicitly and practically rather than outwardly. The installation creates a multi-generational vessel, through which I have learned to accept my ancestors’ non-linear, disjointed stories. After all, remembering our family, rituals, and stories has been our tradition since the first conversions were forced on us in Inquisitorial Spain.