As a first-generation American, I am the youngest of three girls from a turbulent Iraqi-Jewish family from Bombay (known as Baghdadi Jews). While my work has consistently had psychological and social underpinnings, I turned to my cultural and familial heritage to delve into the root of the influences, gendered traditions, and patriarchal systems that perpetuate over generations and shape our beliefs and perceptions.

My current ongoing series, The Fez as Storyteller, explores the impact of this legacy through mixed-media sculptures and two-dimensional works that integrate a range of materials: digital printing combined with fabric, sculpture, paper, trims, embellishments, and cultural symbols of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and Sephardic traditions. I use the fez cap, a traditional Ottoman headgear, as a structural base for storytelling to signify the foundation established by my forebears who left Iraq for Bombay (Mumbai) to become traders of the hats in their adopted land. The fez cap was worn by Muslims, Jews, and Christians. Early in the 19th century the fez was deemed a symbol of modernization and the wearing of the turban was banned. Ironically, as it became mainstream attire, it was outlawed by Turkey in the following century, again in favor of modernization.

When I began exploring the concept of the Temple for an exhibition, Silent Witnesses: Synagogues Transformed, Rebuilt or Abandoned, I recalled two synagogues: the Magen David synagogue in Byculla, Bombay, where my father’s family worshiped, and Knesset Eliyahoo in Bombay, where my mother’s family attended. My father, who knew Magen David’s glory days, would recount tales about his rigorous training in Sephardic style prayer in Hebrew and Aramaic, and how he would sleep under the Bimah in the synagogue during High Holy days when prayers continued deep into the night. Myriad cousins have celebrated marriages, bar mitzvahs, and many important events in this historic building. These synagogues also became the sites for my continuing examination of gender bias in Sephardic traditions and temples.

Set in the Magen David synagogue, Red Fez: Boy, Woman, Byculla, Bombay criticizes the patriarchy in Sephardic and other Orthodox synagogues that continue to maintain segregated seating by gender. Males, regardless of age, sit in the main sanctuary with the liturgical objects and sacred rituals. Women are obligated to worship in the upstairs gallery further away from the focal point in the synagogue. Red Fez: Boy, Woman, Byculla, Bombay depicts a young boy in the main sanctuary standing next to the Bimah and lying underneath it – a location prohibited to women during the prayer service. The fez cap juxtaposes these composited digital representations of a young boy with images of women in the upper level of the synagogue, and the staircase leading to the separate women’s section. The fez cap’s fabric is Indian silk embellished with gold embroidery, and the customary tassel of the fez is replaced by the traditional fringe found at the four corners of a Jewish prayer shawl knotted in the Sephardic style.

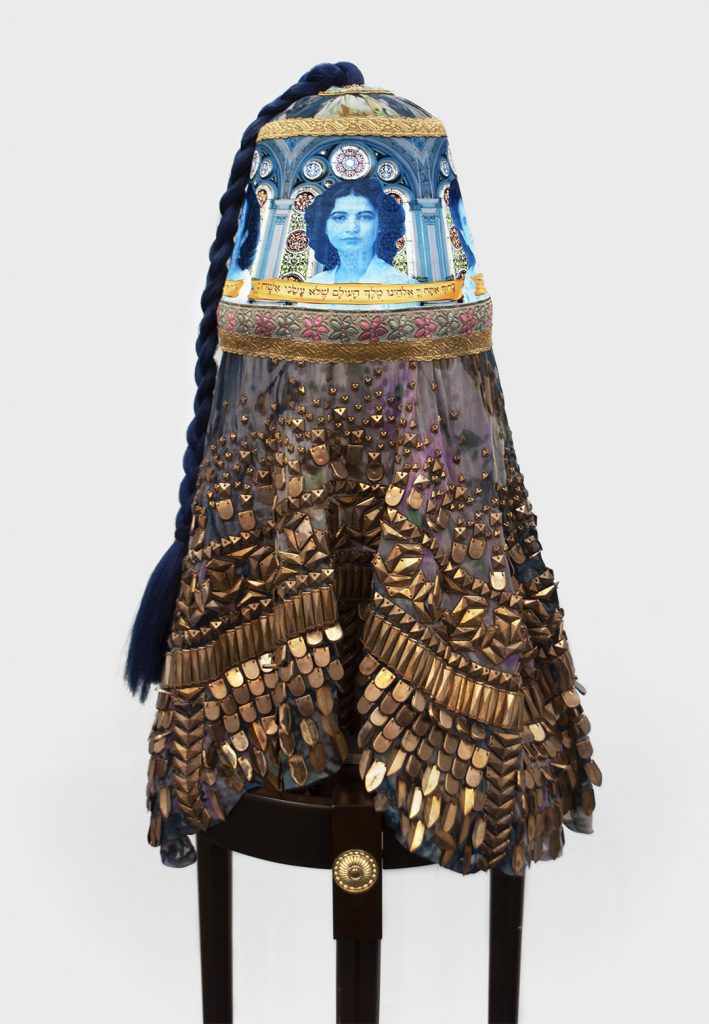

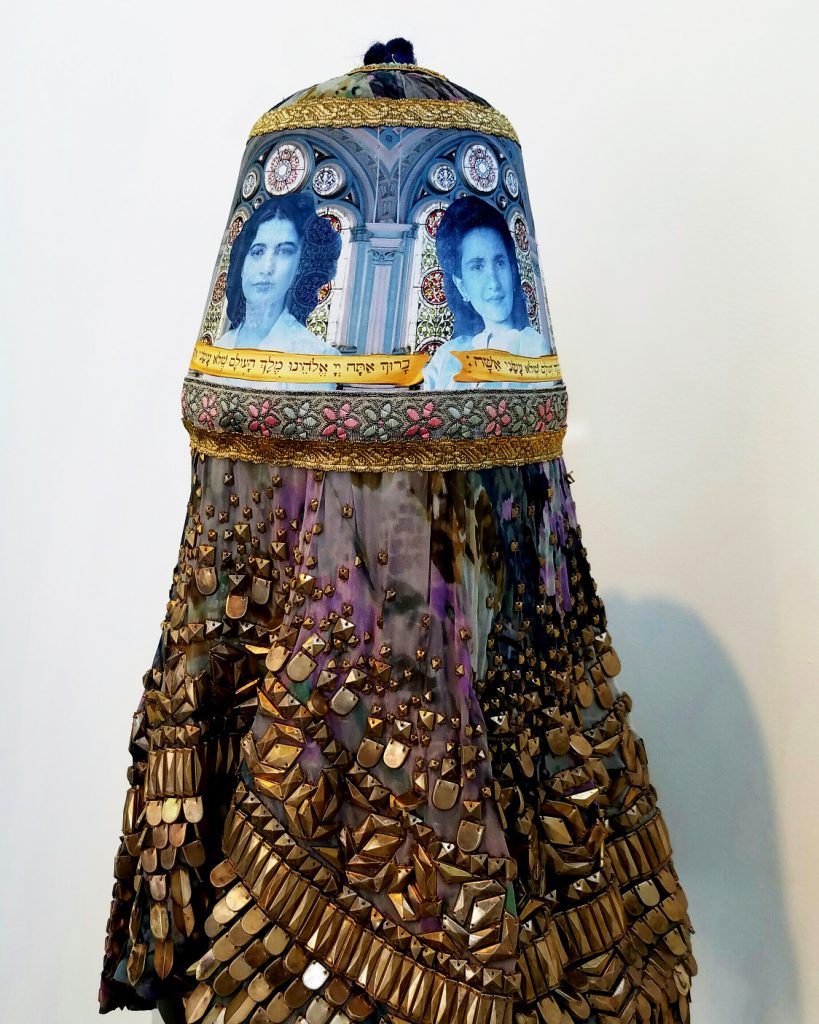

In F-Ezra: Made a Woman, portraits of women from my mother’s family surround the fez cap, and a long dark blue braid replaces the usual tassel. Photographs of Florrie, Eva, Margaret, Mozelle, and Diana are framed by interior images of Knesset Eliyahoo. On gold banners, I highlight the traditional morning blessing recited daily by Orthodox men in Hebrew: “בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה’ אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם, שֶׁלֹּא עָשַׂנִי אשָּׁה”. This translates to “Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the universe, who did not make me a woman.” For this fez, I included a veil to reference a harem girl, a kind of plaything; it also suggests a form of modesty and covering. Conversely, the brass studs on the veil evoke armor to deflect or fight the notion that women are subservient. The wordplay in the artwork title also centers my maternal family surname: Ezra.