“We stood on one of the temple’s elevated platforms. A wide, clear view of the earth spread out before us and we drank it in. But soon a stirring became discernible in this smooth, calm scene. It swelled and grew. The land appeared to surge in great waves. The sky darkened and contracted. It was as if the entire world drew together into this one point with terrifying force.”

–Walter Benjamin, “Schiller and Goethe” (c. 1906–12)

Temples often defined the development of ancient cities. Not only were they the core of spiritual and ceremonial life, but temples have historically served much broader roles as political and civic centers. They are commonly understood to be religious spaces — sites of worship, prayer, and sacrifice — yet, on a fundamental structural level, temples are ritual spaces.

Ritual in the context of organized religions describes regular practices determined by religious law. In contexts not explicitly religious, ritual is social custom, which can equally be established through law. It would be a mistake to assume these modes of ritual are mutually exclusive, as modern rhetoric of the “separation of church and state” would have one believe. The temple as an architectural form is that of ritual, of regularizing and justifying social customs. Among their numerous functions, these often monumental institutions were known to house monarchs and bureaucracies, manage public affairs, establish infrastructure and legal codes, and act as storehouses or treasuries. Specific operations have of course varied between civilizations, but these tendencies can be found in ancient urban cultures from as disparate regions as Mesoamerica and South Asia.

The sprawling cities of the Maya, dating back about 2,500 years ago, were loosely constructed around such religious and political centers, marked by towering stone pyramids where dynasties reigned or were entombed in death, sacrifices were offered to deities, stars in the night sky were studied, and adjacent ball courts hosted sporting events. Across the globe, the Tamil built communities likewise from central temples. By at least the 3rd century CE, rulers planned agraharams, or neighborhoods of row houses along streets with local temples at their endpoints, originally meant for a priestly managerial class. When the Chola Empire conquered the city of Thanjavur in 850 CE, the king immediately erected a temple. The city’s current centerpiece, the Brihadishvara Temple, was built at the turn of the 11th century by a later monarch, and along the lines of the agraharams, it provided surrounding farmland to its hundreds of employees, pushing the economic development of the encircling area.

These cases exemplify a much wider intersecting of the spiritual and legal. In fact, the two are inseparable when tracing the social and political relevance of temples through human history. Even in the Mayan example, when the houses of deities and rulers could be distinct, they still occupied the same precincts and in proximity could be conceptually associated. At the same time, physical adjacency and unity only represent the relationship of spiritual organization and governance in literal terms. In function, temples develop social normalcy and provide significance to the order of the day.

It’s no coincidence that many current buildings of state government resemble temples, for they have long been a key tool of rulers. If not obvious in architectural style, the sheer scale and central placement within a city accomplish similar results. Like many recognizably hierarchical civilizations of old, modern states present a divine image to justify their rule — whether they glisten in the sunlight, pierce the heavens, or stand as a wall that casts a shadow over the square below, a supernatural aura is imposed by government architecture. Such design continues the monumentalism and striking optics of larger ancient temples, some of which sat atop hills and peaks or intentionally resembled them. Even the columns of Greco-Roman temples at least had some likeness to tree trunks, but contemporary centers of civilization have become substantially less naturalistic, designed instead as lustrous and precisely geometric monoliths.

The Baharestan, the old residence of the Iranian Parliament assembled in 1906, featured a façade of round, ornate columns not unlike many other houses of legislature at the time. Following the 1979 Iranian Revolution and disbanding of the Senate, the unicameral Parliament occupied the former Senate building, designed in a sharp mid-1950s modernist style by Heyder Ghiaï. The exact, squared edges of the structure and domed interior strayed dramatically from resemblance of nature, and the columns that did exist on the building’s exterior were rectangular and chain-like, decidedly removed from anything seen in the organic world. Since 2004, the Parliament has been located in a third building in central Tehran, a slanted pyramid pointing toward the sky. In a sense, its upward form roughly harkens back to the regional architecture of 3,000 years ago, like the Elamite ziggurat of Dur Untash, which once directed its towering layers toward the heavens in honor of a deity. At the same time, Tehran’s Parliament building is not stepped as Dur Untash was, instead honed sharply like the tip of an obelisk, making it scarcely scalable.

The pyramid here demonstrates one trajectory of the temple into urban civilization. In some early ceremonial practices, a worshipper might travel to an altar atop a mountain — a ziggurat in this case reproduces the phenomenon, placing an altar at its highest point to which the worshipper ascends via staircase. The temple comes to appear as a mountain, but stemming from its construction by the order of monarchs, its scalability and access to the summit becomes increasingly exclusive to a priestly class. The worshipper ceases to ascend the mountain, and the mountain instead begins to descend upon the people below as though from on high. The Parliament building in Tehran comes architecturally full-circle in its return to the pyramid form, but it is even more visually abstracted from the natural world.

Some state buildings appear closer to what one would understand as a classic temple, such as the popular Corinthian style of the Roman Pantheon, but their naturalistic style, that which reminds one of their roots in reality, is eventually replaced by entirely non-naturalistic design — not merely applied to the individual architecture of the buildings alone, but the wider configuration of cities as a means to highlight them. No longer have they sprung up from the ground but have floated down to the earth from the heavens, planting roots in the earth’s crust in the form of radiant roadways.

This slick architecture, despite being anchored to the earth, exerts an otherworldly quality, appearing so far removed from nature that it becomes quite alien to the comparably fragile, fleshy human. Many legislative houses have been designed as megalithic slabs — structures as disparate as the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s Palais du Peuple in Kinshasa and Russia’s White House in Moscow both draw from temples of ancient cultures and break further away from natural phenomena. The legacy of the temple is considerable when comparing these recent designs to those still observable today from thousands of years ago. The Babylonian ziggurat at Dur-Kurigalzu, for one, contains the ingredients for the aforementioned buildings: its base evokes the block-like Palais du Peuple, and the stone remainder of its upper pyramid juts out like the main structure of Moscow’s White House, both looming above wide open spaces below. While it now communicates a fuller disconnection from nature, and human beings for that matter, the bureaucratic architecture of today has deep ties to that of distant yesterdays. This is not to say the trajectory of temple architecture was on a linear, destined path to what can be found in modern state architecture. On the contrary, there are moments in human history when centralized settlements and monuments were organized and later abandoned.

Given present archaeological information, the oldest structure one could call a “temple” is possibly the Gölbekli Tepe site in Southwest Asia, originating in the Neolithic period. What remains in question is the current lack of signs that agriculture had anything to do with the structure’s organization — the basis for gathering seems to have been solely ceremonial, and to the extent that people lived there, it was likely only seasonal. From this, one can assume a back-and-forth between the proto-urban settlement and nomadic life, moving from centralized to decentralized forms of society during different parts of any given year as the people journeyed from highlands to lowlands and back again.

The lineage of temples is a dialectic of the natural and supernatural, the earth and sky, the ruled and rulers. There isn’t necessarily an explicit dualism with a hard line drawn between the worldly and otherworldly — a temple rests somewhere along the way from one to the other, ever-changing over the course of history. Like a tree stretching upward from the soil, it exists in the blurry and contentious space that is neither earth nor sky yet is somehow of both at the same time.

A duality of temple and city also emerged in this lineage, and from this came another of city and culture. The inner sanctuaries of temples were most fundamentally spaces, walled territories usually designated as sacred. As the point around which urban life revolved, human cultures became associated so closely with these spaces that the cities which expanded outward from temples were understood as derivative of them.

The Mesoamerican city of Teotihuacan, settled around 100 CE, is particularly known for its colossal temples and urban design. Along a great avenue is its largest monument, the Pyramid of the Sun, as the Aztecs named it centuries after the city was abandoned. The Aztec city of Tenochtitlan, founded in the early 14th century, took specific cultural influence from the nearby remains of Teotihuacan, and its grand architecture and infrastructure reflected this understanding of common ancestry. Like its predecessor, a central temple (among other surrounding temples) was associated with the city’s origins, said to indicate the sacred heart of the Mexica people’s promised land. After the Spanish laid siege to the city in 1521, the temple complex — known as the Templo Mayor — was destroyed, and a cathedral was built in its place, still standing in what is today called Mexico City. The temple of Tenochtitlan was such a cultural matrix that it stood as a marker of the people’s tie to the city and territory itself, thus its collapse at the hands of the Spanish symbolized the demise of Aztec civilization.

Ambiguity in the lineage of temples has sometimes turned into conflation, equating and fusing two (or more) distinct phenomena until one is indistinguishable from the other. This is no synthesis but a leaning heavily into one mode while absurdly claiming another, as if to say the people who built and spent particular seasons at Gölbekli Tepe consisted of a society only insomuch as their lives were oriented around that ritual site. The same might be said of how the Aztecs and others understood Teotihuacan, the population of which began to abandon the city around the 6th century, possibly due to public revolt against rulers, ecological crisis, or a combination of factors, effectively rejecting the temples and the social structure based around them. The prioritizing of central territories indicated by monuments has a devastating social consequence that can be recognized in the example of the Spanish assault on the Aztecs: In this conflation, it was not the people who built the city, but the city — and its temple — that built the people. Thus for the invaders to demolish architecture was to destroy the culture and people who constructed it.

—

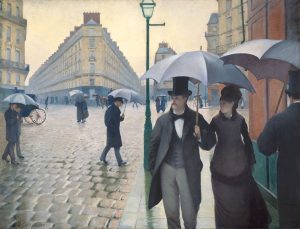

Framed within the long streets of Paris, after the city’s 19th century state-commissioned reconstruction by Baron Haussmann, “the temples of the bourgeoisie’s spiritual and secular power were to find their apotheosis,” argued Walter Benjamin in his unfinished study of the city, The Arcades Project, written over the course of the 1930s. The fantastic imagery of unveiled monuments was “rendered in stone,” producing a permanently surreal, dream-like reality. In Benjamin’s brief nod to temples of secular power, one might recall the buildings of state government that stood during his time and can still be found in present-day Paris. The Palais Bourbon, home to the French National Assembly, is a clear example — its neoclassical façade explicitly mimics those of Classical Mediterranean temples, such as the Pantheon of Rome or Acropolis of Athens.

These temples pepper the city further in the form of “cultural centers” — universities, theaters, museums, and other spaces of the arts and sciences. Like many legislative buildings in Europe and its former colonies, the Greco-Roman temple was a widely popular model for other institutions, public or private, from the 18th to mid-20th centuries. The art historian Carol Duncan, in her 1995 essay “The Art Museum As Ritual,” noted that the architecture is typically understood as mere metaphor, but this assumes a “sharp separation between religious and secular experience.” Once this is questioned, she posited, “we may begin to glimpse the hidden — perhaps the better word is disguised — ritual content of secular ceremonies.”

Benjamin cited churches, train stations, and equestrian statues as exemplifying temples of the bourgeoisie’s power, each acting as a centerpiece in urban life — not so differently from the temples of ancient cities. A major train station, for instance, is a point where railways converge, meeting in a single place and expanding outward from it. The station’s appearance plays its part, but it more significantly facilitates pilgrimage in the name of business. Public statues are frequently framed in a similar manner, albeit on a smaller scale, but unlike a hollow building they can only be observed from an external position.

One can stare down the Avenue des Champs-Élysées and experience in the Arc de Triomphe a feeling perhaps reminiscent of ancient urban temples. The wide streets seem to stretch from the monument like blood vessels extending from a heart through a body. Again, its Neoclassical style was intentional, first representing the power of Napoleon’s French Empire and lasting as a symbol of the contemporary French State, and this is emphasized by the Haussmann-designed arrangement of the roads and buildings of Paris, facing inward like audience seating in a metropolitan theater of history.

In September of this year, the Arc de Triomphe was wrapped in fabric to be unveiled yet again to the public — the last project of the artist Christo, completed posthumously — much to the delight of President Macron. Having been vandalized in late 2018 during the yellow vests protests in Paris, the wrapping and re-christening has clear political implications, renewing the image of state sovereignty through what Benjamin once referred to as phantasmagoria.

This episode is only the most recent sensation of post-Haussmann Paris, a city designed to be a chronic dreamscape. In this phantasmagoria, the city is a stage over which a curtain is repeatedly drawn open and closed again. It asserts a permanent presence of the sensational supernatural, of that which exists beyond human scale and even comprehension — hence why the “Seven Wonders of the Ancient World,” several of which were of the order of temples and tombs, were referred to as wonders. Like great temples built millennia ago, the real is made to appear surreal, connecting this realm to the edge of another. The fantastical is concretized in awesome structures that only exist by commission of monarchs and oligarchs. Though this can be understood as a critique of individual architecture, what is most crucial here is the centrality of temples to cities and the long-running tendency to abstract them from reality. Christo’s curtaining of the Arc de Triomphe renews this wonder for even the local, who may in fact have grown numb to the unrelenting phantasmagoria of the city. In removing it from sight, though it is acknowledgeable in outline, the monument is revealed again as if it is new or renovated, fresh and modernized. Like the Pyramids of the Sun and Moon in Teotihuacan, which were added onto and dramatically enlarged over the course of the city’s centuries of activity, so too is the sensationalism of the Arc de Triomphe reinstated through Christo’s production, only with temporary additions.

The temple’s removal from the recognizable material world finds its current conclusion in prisms reminiscent of 2001: A Space Odyssey, one of the most notable being Brazil’s National Congress building in Brasília. The individual design is impressive alone, but what sets “temples” apart from other architecture is how they are framed within a city or landscape, their configuration as points of concentration — Brasília’s Monumental Axis, like the Avenue des Champs-Élysées in Paris or even the Avenue of the Dead in Teotihuacan, directs attention to its magnificent centerpiece. Their avenues set the stage. In the case of Brasília, the majority of the significant buildings lining the avenue of the Monumental Axis were designed by the same architect, Oscar Niemeyer, presenting an even more direct, homogenous vision of the state’s historical placement. The route passes by cathedrals, memorials, and palaces before reaching the National Congress, as if to suggest the existing state, represented by its legislative house, was the next logical step along the historical pathways of these temples, and perhaps the last. No matter how dazzling, Niemeyer’s Cathedral of Brasília is merely a distraction along the road to the National Congress. Thus amazement, wonder, and a sense of divine presence on earth — however removed from theological bases — becomes associated with organized human domination. Rulers, a sinister form of the superhuman, become the precondition for beauty at least and utopia at most.

The “secular temple” is a misnomer, for temples have always been “secular” in that they literally exist in and order this world. To the masses they present values and ideals as well as social attitudes of their respective civilizations, and this quality has gone unchanged since the dawn of the temple. Yet this relatively static function within human societies generates far worse than the justification of authoritarian power. A temple and its associated bureaucrats can even be conceived as eternal, occupying the flow of time itself. What is “rendered in stone” is the immeasurable fantasy of power.

—

The comparison of museums to temples is rather popular. As stated earlier, a museum may reproduce the architectural style of ancient temples, but even if this isn’t the case, plenty are still built in such a way that emphasizes their grand significance. On the inside, there may be artifacts removed from temples, or, as seen in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, entire temples themselves can be stripped from their locations and rebuilt within the confines of a gallery. This is the case of the Temple of Dendur, the Roman-built ancient Egyptian temple that was deconstructed and relocated to the United States in the 1960s.

Germain Bazin, a former chief curator at the Louvre, once said an art museum is “a temple where Time is suspended.” This is perceptibly correct, but the halting of time is a magic that manifests not from the mystique of the museum itself but its temple-derived aspects, thus this power is wielded by other institutions stemming from that same ancestry. The cessation of the flow of time follows its management by temples and their leadership. In Islam, the public call to prayer, or adhan, is projected outward from central mosques fives times a day. Christianity has traditionally announced a similar call to prayer seven times a day with the ringing of church bells. Temples have mandated and continue to administer ritual practices within time, such as dictating when offerings can be made, when services are to be held, and even when to light candles. One’s very perception of time in daily life can fall under the temple’s spell like the hands revolving around a mechanical clock.

The temple, firmly planted in the present, in reality, has wedged itself into the fluid duality of the worldly and otherworldly. It stakes total claim to the surreal and shrouds it with realism, secured in closed rooms and only giving the public a taste. Even museums open to the public contain deep vaults of artwork “not on view,” hidden from sight like the holiest treasures of temples. What the museum signifies as an offspring of the temple lineage is a disregard and even dislocation of the future, which the temple initiated in first mediating and later sealing away possible existence beyond the present, beyond the world as it is known, and beyond reality itself. The temple blocks the flow of time like a cork stops the flow of water from a bottle. It perches upon the precipice of the real, brushing against the dimension where only dreams take us, the future.

The “secular temple” upholds this practice. In the museum, it appears in mutated form, no longer mediating the future but now redefining it as a continuation of the present. A piece of Surrealist art is mounted not as a fragment of the utopian future but as a figment of a previous cultural paradigm that has progressively culminated in the reality of today. The present is painted as the history of an eternal past, as its rationalized conclusion, while a doctrine of futurism shrouds tomorrow in a cloud of an idealized now. What would otherwise be supernatural is concretized in temple architecture and its modes of presentation, creating a cultic permanence. The phantasmagoria Benjamin identified nearly a century ago is motionless in the instance of the here-and-now, yet it moves in place at blinding speed. The ancient temple bends the senses of time and space, sitting in the blurriness between the earthly and deity, while the modern temple, eventually developing from this legacy, has caused one to consume the other.

Commonly, the most sacred rooms of temples are reserved for priestly entry — the divine is locked away from the masses. “Secular” temples seal away politics. In dictatorships and republics alike, the masses are merely “represented” by politicians and have no direct power over the codes that command their lives. The temples, which are also said to “represent” the public aesthetically, strip not only agency but selfhood from the people. A culture, and thus an individual’s sense of identity according to a group, is fixed to the stone of the architecture that “represents” it. A house of legislature is not the people but “represents” the people, even from hundreds to thousands of miles away. The elites who become such “representatives” emerge from the monarchs and priests of old, who presided from their temple peaks and pulpits. Like sacred ground, the State is made largely untouchable, even for those who worship it.

—

The Temple Mount of Jerusalem is said to be the point from which the earth was formed, the center of life, giving reason for many Jews to direct their prayer toward this single point of origin. Like the mouth of a bottle, the Mount is where the divinity of God, entering from beyond reality, meets the terrestrial world of humanity. The divine presence is the divine in the present.

A temple is a point of concentration. In Judaic and Islamic traditions, worshippers have historically faced their respective central temples even from such distances that they are no longer visible. The orientation toward single monuments in these examples is stretched from a local to global scale, from the city to the entire world. In a short fantasy fragment, Benjamin once described the depths of a temple as seemingly inhabited by “magnetic forces” — such is the fantasy of the temple in reality.

This magnetism distinguishes the temple from other forms of architecture. Other structures are lived in and with, absorbed by the human who passes by and through their walls. Use and perception, touch and sight, define the appropriation of buildings, according to Benjamin in his famous essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” But concentration remains in famous buildings as approached by travelers, a relationship developed on the basis of distance. A pilgrim, journeying to a matrix, closes the physical distance only to encounter the ineffable, an even vaster distance.

What is most curious in Judaism is its missing Temple. Those who turn to it in prayer face a hypothetical building, a wholly invisible and intangible symbol. The destruction, regardless of historicity, not only accentuates the relevance of the Temple as an inflection within Jewish theology but transmutes it into something wholly uncharacteristic of any standing temple, transcending its former position at the hinge of the natural and supernatural. Scheduled times for recurring ritual practices have carried on, but unlike Islam or Christianity, there is no adhan or tolling of bells directing the public’s attention to the Temple, as it does not exist and therefore cannot perform such outward calls for spiritual orientation.

The pilgrim who makes their way to Jerusalem finds no Temple, but a plot of land surrounded by walls defining the sacred space. The divine presence persists sans temple, just as Jewish culture and people have persisted. According to Maimonides, even with the Temple in ruins, the site itself remains eternally holy. A worshipper is expected to revere the space as if the Temple were still standing, and this includes respecting the exclusiveness of the Temple’s innermost sanctum. This was not necessarily to bar entrance to the Temple Mount entirely — in theory, much of the site could be entered with permission, but the lasting uncertainty of the inner sanctuary’s precise location led to determinations that, in walking the grounds at all, one may unintentionally tread through the holiest space. Maimonides’ argument and the sanctuary’s location remain disputed among scholars. As this dilemma has yet to be resolved, a pragmatic interim solution has been the territorial conflation of the innermost sanctum and the full area of the Mount, which many Jews continue to observe. The sanctuary, where the divine presence was believed to connect to the physical world, is expanded in potential. While the area it inhabited cannot be clearly determined, it has gained the potential of being situated almost anywhere on the Mount. The dwelling of God is no longer the Temple architecture — its destruction exploded the possibility of where the divine could rest. The Mount without its Temple is open air, an open square. With the place between earth and sky unclogged, each is able to mix with one another in this zone of life. The future, unobscured by the structures of the present, becomes realizable — the realms of potential and possibility are opened.

This possibility comes with a caveat. A conflation lies in this situation. On one hand, the divine has been released into the greater universe. In every piece of matter can be found the seeds of surreality, of the otherworldly, of the future. The released divine can act as a catalyst for realization and a unifier of humanity. As the Temple itself is hidden, its surrounding social customs can be deeply scrutinized. The center could reasonably be anywhere, and even its placement on the Mount at all can be called into question — given the ambiguity, even seemingly absurd answers become possible. This ambiguous center could be rejected altogether, with new centers constructed elsewhere. Peoplehood can be defined independently from ritual architecture and beyond territory. The city center no longer has to be defined by a monument of ruling power, and if the space does remain a city center, it has the potential to be a completely transparent zone of social, spiritual, and civic life.

On the other hand, the divine has sunken into the ground of its foundation. A territorial nationalism erupts, acting as a representative of the people, which threatens to reaffirm the centralization and thus reseal the utopian energy unleashed — resealing through monumental renewal. It would see the removal of a whole people from the broader world through architectural conflation and in isolation reduce it to a singularity in a sea of nothingness. With the bottle opened, its water can flow outward, but dirt can just as easily be stuffed inside.

The renewal of monuments is a security measure enacted by the gatekeepers of the future. When a temple of spiritual or secular power is hidden or demolished, the future becomes unpredictable, enabling a utopian potential. To unveil temples again, to reproduce them, is to shove a cork back into the bottle of time, sealing the fate of humanity. The temple occupies the space of the fantastic, and in its realism devours human dreams. If the dream, the surreal, is embodied by the temple, such a structure cuts humanity off from the dream that is its utopian future. While the coming of such a time is possible, it could just as easily never arrive.