Ever since my first years at the Uziel elementary school in Bnei-Brak, or maybe even since kindergarten, I heard the story about the Western Wall covered in heaps of garbage. According to that story, the reigning Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent decided to build his palace near the wall, but only when the garbage was cleared was it finally discovered, giving the adjacent Dung Gate (Sha’ar Ha’ashpot, or Bab al-Maghariba, the Mughrabi gate in Arabic) its Hebrew name. In the years that have passed since I first heard the story, I did not ascribe any interesting meaning to it or its main characters. I stored it somewhere in my memory, ignoring the strange infiltration of this Ottoman-Jewish tale into the curriculum of the sovereign Jewish nation-state’s education system.

An incidental encounter with one of the Jewish books in which this story was first mentioned (to the best of my knowledge; although it has roots, as will be explained hereinafter, in local Muslim traditions) revealed the story to me as a manifestation of the Jerusalemite Jewish collective consciousness at the turn of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. R. Moshe Hagiz’s book Parashat Ele Masei (“These are the Marches”) was published in Altona in 1733 and contained a narrative describing the discovery of the Western Wall and the building of the Haram al-Sharif. The political significance of Hagiz’s narrative is in its conceptualization of “Eretz Yisrael” beyond the limited scope of its current secularized and nationalized notions; that is to say, beyond the exclusive Zionist and colonial conception of the land.

In “Rediscovering Ottoman Palestine: Writing Palestinians into History” (1992), Beshara Doumani argues that the emergence of European colonial missionary and research societies during the nineteenth century and, more forcefully, the Zionist immigrations, imposed a Protestant biblical lens through which Palestine was perceived. This lens brought about the total erasure of the concrete Palestinian space, its people, and its history, henceforth pictured as no more than “remnants” or “fossils” of an ancient biblical era. Doumani’s argument clarifies the processes that secularized and nationalized Jewish images of the land as well. As Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin also demonstrates, these processes involved the total severance of the cultural and political picture of “Eretz Yisrael” from the real and present Palestine and also from the local collective consciousness of Palestinian Jewish communities. Zionist discourses pictured the latters’ existence as that of an “Old Yishuv,” which the Zionist “New Yishuv” would inherit.

The Zionist historiographic references to “Old Yishuv” spaces sought to confirm continuous Jewish existence in the land, all the while negating the collective consciousness of these Jewish residents in the land, who it depicted as exilic. One example can be found in Yitzhak Ben-Zvi’s article “The History of the Jewish Settlement (yishuv) in Kfar-Yosef,” published in the first issue of Me’asef Zion, the journal of the Society of History and Ethnography in Palestine, in 1926. Ben-Zvi presented the Jewish community of the Palestinian village Kfar-Yasif as indicative of the continuous Jewish agricultural presence in Eretz Yisrael, evident in his use of the term yishuv in the title. He struggled with the fact that this Jewish existence was invested in a broader regional social fabric, picturing it as a “foreign environment, which is distant and torn from any other Jewish settlement.” His use of an invented Hebraized name of the village — Kfar-Yosef instead of Kfar Yasif — also reflects this struggle. Adopting the colonial language of yishuv, Ben-Zvi subordinated eighteenth century Galilean Jewish existence to a separatist spatial logic.

The nationalization of the space by Zionist writers crystallized a conception of the land as national territory, often expressed through aspirations to reactivate biblical images of the land and restore a glorious, sovereign Jewish past. The whole repertoire of symbolic meanings signified by the rich theological term Eretz Yisrael were unloaded onto the concrete Palestine, henceforth forced to carry this theological burden. As Haviva Pedaya argued in Expanses: An Essay on the Theological and Political Unconscious (2011), “The return to the concrete Eretz Yisrael after centuries of conceiving it symbolically means that, on the one hand, there is ordinary life there—which always carries with it a subjective system splitting spatial reality into the imaginary, symbolic, and real—and, on the other hand, Jewishness maintains a psychic cache of…various, diverse theologies and systems that each uniquely conceptualize a relation to this non-present place.”

Hagiz’s narrative in Parashat Ele Masei conveys a different conception of the land, one connected to its contemporary political context and shared by other local indigenous communities. It signals the basis for a different narrative of Jewish existence in Palestine-Eretz-Yisrael, one that can form an integral part of imagining Palestine’s decolonization. Mahmood Mamdani, in his book Neither Settler Nor Native: The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities (2020), suggests decolonization implies primarily a decolonization of the political, a process involving both natives and settlers as they transcend the political logic of the colonial nation state in which the binary system of settler and native inheres. The “survivors” of the modern political order should go beyond the politicized, majority/minority boundaries set by colonial forces in order to create a different political community. Though I accept Mamdani’s model of decolonization as a process necessarily shared by both settlers and natives, the undifferentiated inclusion of both in the category “survivors” might thwart this very political effort. While the native seeks justice and the end of the colonial order, the settler seeks to crystallize a collective self-consciousness attached to a non-colonial structure.

Following scholar Raef Zreik, I suggest reading Hagiz’s narrative as one that enables an understanding of decolonization in which “the settler stays but colonization goes.” In other words, alongside the rectification of injustices caused by ongoing Zionist colonization, reading Hagiz’s narrative can generate an understanding of decolonization as a political horizon in which the colonial practices of the Jewish settler stop and all his or her individual and collective privileges are abolished, accepting full equality with indigenous Palestinians. Amid a Jewish inability to distinguish between “being” and “being colonial,” Hagiz’s narrative may constitute an important tool in what Zreik has described as the “surgery that can elicit the national flesh from the settler-colonial skeleton.”

Hagiz was born in Jerusalem in 1672. He was the son of Ya’akov Hagiz, the head of the Beit Ya’akov yeshiva established by the Livornese brothers Avraham Yisrael, Ya’akov, and Raphael Vega. After the death of his father at the age of two, Hagiz grew up in the home of his mother’s father, Moshe Galante, who inherited Hagiz’s father position as head of the yeshiva. Hagiz was raised in a unique historical period in Jerusalem. It was, as Dror Ze’evi termed it, the “Ottoman century,” standing between the earlier Ottoman period, during which Mamluk influences remained significantly present, and the late 18th century, during which the influence of the European trade networks grew stronger. These years were characterized by the “rule of the Ottoman culture and its confident worldview.” This period was also characterized by the rise of Jerusalem as the main urban center in Palestine and the relative flourishing of the Jewish and Christian communities of the city, their integration into the whole urban fabric.

Following the death of his grandfather in 1689, and the yeshiva’s loss of financial backing after Raphael Vega’s death three years earlier, Hagiz searched for resources that would enable the rehabilitation of Beit Ya’akov. In 1694, following the death of his wife, he went on a journey during which he arrived at Rosetta (Egypt) and Livorno. Although Hagiz managed to gain commitments for financial support for the establishment of a new yeshiva in Jerusalem, led by him, his rivals in Jerusalem sent letters to the Jewish philanthropists thwarting his efforts. His failure to reopen the gates of his father’s yeshiva marked the beginning of a period during which he moved between the major urban centers of the Western Sephardic Jewish diaspora, which at that time played a major role in colonial maritime trade networks.

Hagiz’s journey between major port cities such as Rosetta, Livorno, Venice, Hamburg-Altona, and Amsterdam — where he led the anti-Sabbatean controversies against Nechemya Hayun, broadly analyzed in Elisheva Carlebach’s seminal book on Hagiz, The Pursuit of Heresy (1990) — as well as his efforts to encourage the rich Jewish communities in these cities to financially support the Jewish communities in Ottoman Palestine, reflect another important aspect of this historical moment. As Matthias Lehmann argues, these years were characterized by the emergence of a “pan-Jewish” network in which Jews from different and distant geographic areas “were challenged to think of themselves as part of an intertwined community that could act collectively in the present” and that was connected through “a shared sense of solidarity with the Jews of contemporary Palestine.”

This communal sense of the importance of Jewish existence in Palestine should not be considered trivial or self-evident. Actually, it required ideological justification, and this requirement stood at the heart of the activity of emissaries (sheluhey de-rabanan or shadarim) sent from Palestine to Europe, North Africa, and the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire in order to raise money for the benefit of the Palestinian Jewish communities. This network of shelihut was conducted under the supervision of the Committee of Officials for the Land of Yisrael in Istanbul (Va’ad Pekidey Eretz Yisrael be-Kushta), indicating the centrality of the Ottoman imperial context to the emergence of the Jewish network. Hagiz’s portrayal of the Western Wall and Haram al-Sharif should be read against these local and global contexts as both a picture rooted in the local urban imagination of Ottoman Jerusalem and its connection to the imperial center in Istanbul, as well as an image addressed to the emerging pan-Jewish network connecting major urban centers of the Jewish diaspora.

Hagiz had linked the concrete political status of Ottoman Palestine to justifications of the importance of Jewish existence in the land in his book Sefat Emet, published in 1707 during his first year in Amsterdam, in response to various claims that doubted the sanctified status of his contemporary Palestine-Eretz Yisrael. This essay opens with a certain question addressed to Hagiz, brought in Portuguese with a Hebrew translation, that questions “the measure of the sanctity of the holy land” due to the fact that some scholars (me-eize me’aynim) claim that “nowadays […] all the other lands are actually the mentioned city Jerusalem and in any place that we shall call god he shall answer.” This question reflects various cultural tendencies that became common throughout the Sephardic Jewish diaspora and doubted the religious status ascribed to contemporary Palestine, a part of the broader questioning of the authority and meaning of the oral law. In Sefat Emet, Hagiz confronted these attitudes. He used different motifs common in the Jerusalemite Muslim literary genre of Fadail al-Quds as well as in earlier Jewish traditions that imbued the place of the Temple with a primordial and eternal cosmic sanctity. As opposed to those who identified any city they resided in as their own Jerusalem, Hagiz placed Palestine as the sole place of the “channels of abundance and blessings and the reception of prayers (tsinorey ha-shefa’ veha-berachot ve-kabalat ha-tefilot).”

Hagiz also pointed to Jerusalem’s concrete political status at the beginning of the eighteenth century. In his discussion of the position of Rabbeinu Hayyim, a French medieval Tosafist, who questioned the validity of the precept that a spouse can today compel her partner to immigrate to Eretz Yisrael, Hagiz pointed to the different political status of the land in the Ottoman imperial context:

[…] since in Rabbeinu Hayyim’s days there was a controversy between the kingdoms that ruled Palestine and the kingdoms of the other lands, but nowadays, when all the visible land is ruled by these two kingdoms of Edom and Yishma’el […] and usually there is peace between them and the danger is not common […] there is definitely a commandment to live in Eretz Yisrael […]

Sefat Emet was published eight years after the treaty of Karlowitz between the Ottoman and Habsburg empires was signed, which enabled a secured pass between Europe and the Middle East. This new political situation stands as the background of Hagiz’s justification of the obligation to live in Eretz Yisrael. Hagiz put the eternal status of Jerusalem, as manifested in various local traditions, in relation to a discussion of its current political context.

A prominent example of Hagiz’s use of the local Palestinian Jewish persepective in his essays addressed to the broader Western Sephardic Jewish diaspora is his rich narrative of the discovery of the Western Wall and the building of the Haram al-Sharif, published in Parashat Ele Masei 26 years after Sefat Emet and after his expulsion from Amsterdam for his harsh anti-Sabbatean polemics.

Hagiz’s narrative attributes the building of the Haram al-Sharif to Sultan Selim I (mentioned as “Selim, may his soul rest in peace [nishmato eden]”), who conquered Palestine in 1517. Hagiz claims that one of the buildings in the complex is “in the shape of the first pattern” (ke-ein dugma rishona), following the architectural design of the Jewish Temple. After depicting the complex and showing how it reflects the old Temple, Hagiz relates stories about the discovery of the place of the Temple that he heard from “the scholars and the experts among the Yishmaelites in the history of the Ottoman Empire.” After conquering Jerusalem, Selim built his palace next to the place of the Temple. One day, he saw an old woman who brought a sack of garbage and threw it next to the palace, in a place where he could watch it from his own window. Selim demanded to meet the woman in person and asked her to explain this custom. The old woman explained to him that she was a Byzantine from one of the villages next to the city, and she came to fulfill the order of the Byzantine authorities who ordered to bring garbage to this place since “this was the place of the god of Yisrael, and since they were not able to totally demolish the building they decreed […] this custom in order that its name will be forgotten and the name of Yisrael would not be mentioned on it any more.” After he heard the woman, the Sultan addressed the poor of Jerusalem and promised them money in order to encourage them to clean off the garbage. After one month of work by ten thousand people, the Western Wall was discovered.

This part of Hagiz’s narrative is deeply rooted in local Muslim traditions about the garbage dump that covered the Dome of the Rock and was discovered by Umar Ibn al-Khattab following the Muslim conquest of the land. According to these traditions, the garbage dump was accumulated on the dome as a Christian sign against the Jews, and Umar demanded to clean off the garbage using the help of the peasants from the adjacent villages. The identification of Sultan Selim I, rather than the Caliph, as the one responsible for the discovery demonstrates the role of Jerusalem’s imperial Ottoman context in the local urban self-consciousness. It also reflects the extensive urban operations taken up by Selim’s son and inheritor Suleyman, including the introduction of an organized system of water supply to the city, the building of secure city walls, and the renovations of buildings in the sacred space of the Haram al-Sharif. In Hagiz’s depiction of Selim’s encounter with the Jews, after the discovery of the wall, he suggests they rebuild the Temple. Selim claims that “this is the Lord’s doing and may He cause to return the crown of this building to its former glory, when it was built by king Solomon, in whom my name resides (de-shmi be-kirbo).” The Sultan’s acknowledgement of the similarity between his own name and the Temple’s biblical builder suggests Suleyman al-Qanuni’s self-image as a second Solomon. Unlike his father, however, Suleyman never managed to perform a pilgrimage to the sacred space in whose renovation he invested so much. It therefore seems the characters of both sultans were amalgamated in the local literary and historical imagination, pointing to the connection between the local urban sphere and its imperial Ottoman context.

While trying to respond to the Sultan’s suggestion to rebuild the Temple and finance this operation from the imperial treasuries, the Jews, as described by Hagiz, burst into tears, claiming that although the sultan should be blessed for his generous suggestion they cannot rebuild the Temple since their belief is that “this house will be built under the Lord’s command from heaven, when it will be according to His will, and nobody else’s.” Following the Jews’ refusal to rebuild the Temple, Selim cites Solomon’s prayer during the Temple’s inauguration, according to which “the foreigner who is not of your people Yisrael comes from a distant land for the sake of your name…comes to pray towards this house” and decides to rebuild the sacred complex on his own. Hagiz continues the story and tells that he granted the Jews total permission to live in the city and engage in any craft they choose. And he asked them to “give him the shape of the various sites of the Temple” (tavnit ha-mekomot she-hayu ba-mikdash), patterns according to which he would build the complex. Hagiz also mentions the Haram’s madrasa in which, according to him, study focused on “the merits of the place and its greatness (shivhei ha-makom ve-gdulato).”

Hagiz’s narrative thus imagines the discovery of the Western Wall and the establishment of the Haram al-Sharif as simultaneous, reflecting their mutual connection. The discovery of the place from which the divine spirit, the Shekhina, never left (lo zaza shekhina mi-kotel ha-ma’aravi), the remnant of the destructed Temple, is interwoven with the refusal to acknowledge the historical moment as a moment of redemption — demonstrated on the one hand by the rejection of Selim’s suggestion to rebuild the Temple and on the other by the Jewish affirmation that the contemporary sacred Muslim complex was built according to the pattern of the first Temple. The remnant of the Temple, as the Jewish site of praying and mourning, and the Haram al-Sharif in the pattern of its first shape are pictured as two parts of the same contemporary sacred space. This depiction partly justifies Jewish existence in Eretz Yisrael (and thus the present Ottoman Palestine) as the existence of God’s children “in His own castle (palatin), within its own city,” yet rejects this justification as a moment of salvation.

The first challenges to Hagiz’s depiction can be found in the discussions of the rabbis Tzvi Hirsh Kalisher and Yehuda Alkalai during the second half of the nineteenth century, which focused on the possibility of the renewal of the ritual sacrifices and, in Alkalai’s case, the offer to use European Jewish capital for the destruction of Jerusalem’s mosques and their relocation to a different city in the Ottoman Empire. Kalisher’s and Alkalai’s words were written in a context that already understood Jewish existence in Palestine through a colonial prism. During these years, as Ron Kuzar argued, the commandment of “living in Eretz Yisrael” (yeshivat Eretz Yisrael) began to take a different lexical shape as “settling Eretz Yisrael” (yishuv Eretz-Yisrael). Different forms of the word “colony” were put in brackets next to it. In other words, “living in Eretz Yisrael” became “colonizing Palestine.”

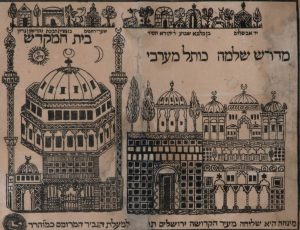

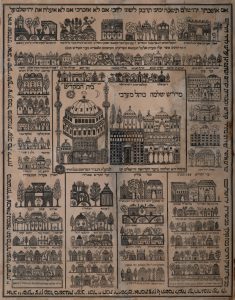

One of the prominent opponents of Kalisher’s program was Rabbi Akiva Eiger. In one of his letters to Kalisher, he cited the words of his son-in-law the Hatam Sofer, who opposed Kalisher’s idea and supported what he understood to be the local Jewish Jerusalemite community’s self-perception: “and the holy community (qehala qadisha) of Jerusalem sent me a terrific picture of the Temple Mount and all that is built upon it and within it also the mentioned Dome, and this is a wondrous thing to see (inyan pele liroto).” The Hatam Sofer adhered to the local description of the place, against Kalisher’s aspiration to supplant the constructed pattern of the Temple in order to build the Temple itself (evident in the latter’s assertion that “in the moment that the license will be transmitted and we will have the ability we will be obliged to fulfill the commandment of the sacrifice”). This picture continues the one drawn by Hagiz. The simultaneous visual presentation of the Temple’s remnant with the extant pattern was common in the genre of tablets made by Jerusalemite Jewish artists and sent to Jewish communities in the diaspora.¹

The ongoing expulsion of Palestinians led by the Zionist movement since its first organized steps in Palestine and the Nakba — the expulsion, expropriation, and prevention of the return of the Palestinian refugees to their lands after the 1948 war; the lightning destruction of the waqf of the Mughrabi neighborhood next to the Haram al-Sharif in 1967 — a destruction whose roots can be traced back to a 1929 interview in which Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak Hacohen Kook named the neighborhood “the disgusting yards (ha-hatzerot ha-menuvalot)” of the “secular waqf of the Mughrabi beggers (ha-”waqf” ha-hiloni shel ha-kabtsanim ha-mugrabim)” and suggested, under the protection of the colonial authorities, to destroy it in order to build a plaza in its place; the current attempts to displace and expropriate the land of Palestinians in al-Araqib, Jaffa, Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan; and the recent Israeli police attack within the al-Aqsa mosque and the horrific flags parade (rikudgalim) all register not only the subjugation of Palestinians but also the subordination of Jewish existence in Palestine to the colonial logic and language of the Zionist movement.

But the picture that Hagiz drew opens a different horizon. Instead of Zionist contempt for the ways in which traditional Jewish communities related to the Western Wall and its desires to impose Jewish sovereignty on the Haram al-Sharif — two faces of Zionist discontent with mourning, destruction, and lack of redemption — Hagiz outlines a possibility of adhering to the whole complex of the Temple Mount, the remnant of the Temple and its pattern, as a vision which is “a wondrous thing to see.”

- On these tablets see: Malka Jagendorf [editor] and Rachel Sarfati [curator], Offerings from Jerusalem: Portrayals of the Holy Places by Jewish Artists (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 1996).