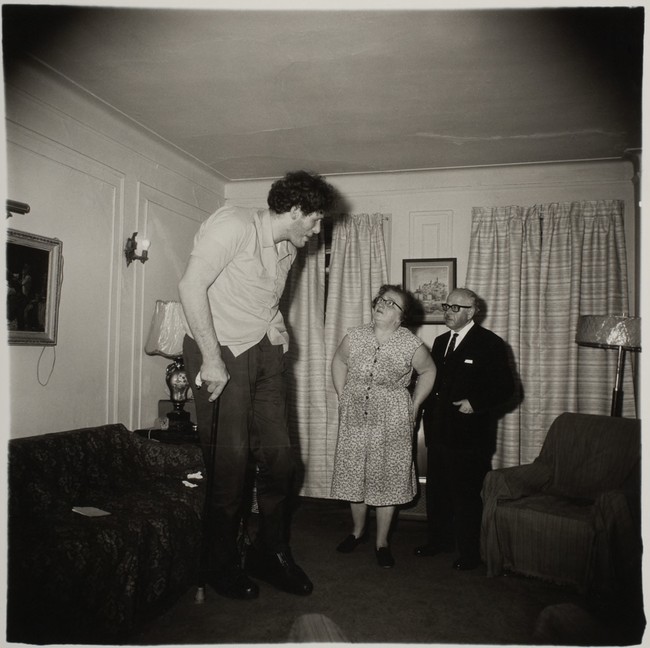

[Image description: In a living room there is a very tall white man. So tall, he appears to be a giant. He is bending slightly so that his head doesn’t hit the ceiling. Next to him stand his much shorter parents, both wearing glasses, looking at him. There are two works of art on the wall, two lamps, a couch, and a chair.]

—

Just before Rosh Hashanah this year, Vogue published an article about a new line of chic, minimalist, modern Judaica designed by a 35-year-old New Yorker named Dana Holler Schwartz. Brought up in a Reform home in Toronto, Schwartz first had the idea for tasteful Judaica while shopping for a mezuzah of her own. She wanted something that matched her personal aesthetic — “contemporary seasoned with the odd antique, clean neutrals with pops of color” — but there was nothing to be found. Figuring that other Jews of her generation and cultural milieu might also feel alienated by traditional ritual accoutrements, she decided to create her own line of Judaica that is “both functional and cool,” with a “modernist Bauhaus-style aesthetic.” Her new brand, Via Maris, offers precisely this: aluminum shabbes candlesticks in muted pastel colors; a monochrome, block-shaped chanukiah; a mezuzah that looks like “a high design vape pen.”

The Vogue article caught the attention of Jewish Twitter, instigating a small but fervent backlash. People took issue with how the article broadly framed the Jewish aesthetic as outdated and ugly. “No offense to my people,” the article begins, “but we’re not exactly known for our understated design sense.” On Twitter, commenters pointed out that Jewish people were once, in fact, major contributors to the development of the Bauhaus design that Schwartz today seeks to emulate. Others mentioned that they own Judaica items that are “traditional,” yet beautiful. One woman suggested that Vogue was perpetuating goyische beauty standards — that the article was the equivalent of telling a Jewish woman to straighten her hair to fit in.

There was something in this backlash that I could understand. I, too, found the millennial, minimalist, assimilationist Judaica unlikeable. The products seemed to match Schwartz’s observance of shabbes, which the article describes as a “phone-free dinner with her husband followed by drinking wine and reading rather than watching television.” For Schwartz, ritual is a type of self-care activity that fits inside another more mainstream identity. And she wants ritual items that do not clash with this identity. Judaica must be objects “whose function extend[s] beyond religious rites.” In other words, things that don’t stick out, things that look nice enough that you might even have them in the house, if you weren’t Jewish.

At the same time, I agreed with the fundamental premise of the article: For an ancient tradition of such narrative beauty, intellectual rigor, and rich veins of suffering, the aesthetic of our ritual objects is generally kitsch, even ugly. I’m not talking about all Jewish artifacts, but a certain Ashkenazi aesthetic that is referenced in the Vogue article, a sensibility that begins with Judaica and permeates outward through the Ashkenazi world, conveyed by things as diverse as a 1.25 liter bottle of seltzer on an embroidered tablecloth at a Bar Mitzvah, or Fran Drescher’s mother in the Nanny. I have observed this aesthetic repeating itself with startling consistency across diasporic communities in Melbourne, Australia where I grew up, and now in New York, where I’m living. I have developed my own phrase for it: the Jewish Ugliness.

It is a confrontational phrase and sure to offend and provoke. But it comes from a place of curiosity, maybe even attraction. That is, although I agree with Vogue’s premise that a certain Jewish ugliness does exist, I don’t believe that it should be neutered with “functional/chic” Judaica that could be displayed alongside the requisite replica Eames chair and Le Creuset dutch oven. Nor do I believe the Jewish aesthetic needs to be redeemed by proud Jews on Twitter insisting on our beauty. In other words, the Jewish Ugliness is real, but worthy of appreciation. There are lessons to be learned from our ugliness, which would be lost if we designed it out of existence.

—

That we decorate our ritual objects at all comes from the principle of hiddur mitzvah, which holds that one can enhance a particular mitzvah by making the ritual more beautiful through ornamentation. This principle was first elaborated in the 2nd century by the great rabbinic sage, Rabbi Yishmael ben Elisha. “Is it possible for a human being to add glory to his Creator,” he asks? “I shall glorify Him in the way I perform mitzvot. I shall prepare before Him a beautiful lulav, beautiful sukkah, beautiful tzitzit, and beautiful tefillin.”

Rabbi Yishmael’s injunction should be read, I think, in the context of his life. Born in the decades just after the destruction of the Second Temple, he was kidnapped by Roman emissaries and held captive for ransom in Rome. In light of this trauma, and the general upheaval of Jewish life in this era, I wonder whether hiddur mitzvah was Rabbi Yishmael’s attempt to re-invigorate the rituals that were suddenly missing their aesthetic center — the Temple. Perhaps it was through ornamentation that the Jewish population, still at the beginning of their diasporic wonderings, could experience and revive what was lost. And it is an ongoing devotion to this reminiscence that makes our aesthetic somehow stuck in time, clashing against modern sensibilities.

Perhaps it was through ornamentation that the Jewish population, still at the beginning of their diasporic wonderings, could experience and revive what was lost.

For me, Judaica is reminiscent of Golds, a shop in Melbourne’s most densely populated Jewish suburb, Balaclava. When I was growing up, it was common to receive Golds vouchers as Bar Mitzvah presents. I remember my dad taking me to the small shop on a Sunday afternoon to use my vouchers and pick a few items. Among the leather prayers books with gold-leaf edged pages, kiddush cups with gem-studded pomegranate motifs, and red velvet yarmulkes with gold string embroidered around the edges, what caught my eye was a picture book outlining, in great detail, what the Temple of Jerusalem looked like. As I browsed the hyper-realistic illustrations of Jewish priests ascending the Temple steps carrying golden incense burners, elaborate chalices, and silver plated shofars, I looked around at the objects in the shop again. They seemed, displayed there in glass cabinets with white neon back-lighting, inadequate simulations of these ancient objects clashing horribly against the suburban Australian landscape outside the window. I wondered longingly about what it would have been like to be around when Jews were actually aesthetically impressive.

This idea was not entirely new to me. At my Jewish day school, the Rabbi had once given a presentation about an institute in Israel dedicated to building exact replicas of Temple-era objects, so that they would be ready the moment the Mashiach arrived. The lecture was held in the school synagogue, an oddly shaped room with bright red carpet, concrete walls, and stained glass. The rabbi stood beneath a bronze menorah lit up with faintly yellow neon bulbs, one of which flickered. His shirt was untucked, his beard unkempt, and he took occasional sips from a bottle of Diet Coke. He looked longingly at slides, projected on the whiteboard next to him, of a magnificent High Priest, dressed in flowing robes, covered in an ornate, gem-encrusted breast-plate. The Temple rebuilt, he said, was about spiritual redemption, but I wonder if, like me, he was also seeking aesthetic redemption. Did he imagine that in the days of the Third Temple we would no longer be diasporic, schlocky, and out-of-place but delivered, whole, and authentic?

—

If one potential source of the Jewish Ugliness comes from the Talmudic principle of hiddur mitzvah, another, more explicit one comes directly from the Torah itself — the second commandment: “Thou shalt not make any graven image, or any likeness of the things in heaven, earth, and sea.” Some interpreted this to mean that any attempt to represent living forms risked diminishing God’s creation and falling into idolatry, repeating the sin of the Golden Calf. While attitudes towards representational art have changed over the centuries and differ between communities — the frescoes of the Dura-Europos Synagogue in Syria, built in the third century, depicted Biblical scenes, as did the mosaics of the Beth Alpha Synagogue in the Jezreel Valley — this injunction has loomed large over the Jewish artistic tradition, which is incontestably modest when compared with Islamic and Christian art.

In Europe, during the 18th and 19th centuries, Judaism’s aniconism was taken by some as a defining quality of Jewish identity and character. For Hegel and Kant, it explained what they perceived to be a preference for abstract ideas and verbal intelligence among Jewish people. For Wagner, it spoke to an inherent aesthetic impoverishment in the Jewish soul. Both positions presupposed an idea that was dominant in European thought at the time; namely, that beauty aligned with moral goodness and progress, and ugliness with degeneracy and backwardness. This idea was deployed not only to make judgements about art but also nature and the human form. Within the rubric of physiognomic science influenced by Johann Kaspar Lavater (1741-1801), character could be inferred directly from the body. So-called “Jewish features” were often associated with abnormality or ugliness, implying the same about the Jewish soul.

One thinker who refused to concede any correlation between beauty and morality was, perhaps unsurprisingly, the Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn. As a departure from prevailing Enlightenment thought, he argued that ugly or misshapen objects do not indicate moral inferiority but alluring complexity. There is, he proposed, a “peculiar pleasure” in encountering an ugly thing, because it elicits what he called a “mixed sentiment,” a complicated and oftentimes contradictory response that draws on many emotions all at once. The conceptual flexibility required to process an encounter with the ugly, he argued, leads to a refinement of intellectual acumen, and is, for this reason, more valuable than pure beauty.

This aesthetic theory was drawn, perhaps, in part from Mendelssohn’s lived experience. Hunch-backed, short, and dark haired, Mendelssohn was perceived by many as an unsightly, deformed, intruding Jew. Although with his radiant and brilliant mind, it was as if he embodied his own aesthetic philosophy. He falsified, through his mere existence, the idea that outer beauty signified inner morality. This so confused physiognomists like Lavater that he considered Mendelssohn to be a kind of anomaly, a Jew with a Christian soul. He frequently, and publicly, challenged Mendellsohn to convert.

Mendellsohn refused. For him, central to the project of modernity was the appreciation of complexity, difference, and contradiction — all of which, he felt, were tied up with ugliness and Jewishness. His appearance and religious identity might have offended Christian European sensibilities, but if the gentiles couldn’t appreciate these qualities, if they tried to beautify out of existence that which aroused “mixed sentiments,” then the project of modernity itself would fail.

—

Although mostly overlooked in his own time, Mendelssohn’s aesthetics, in a way, predicted the shift from romanticism, which focused on sublime, coherent beauty, to modernism, which embraced dissonance and fragmentation. At the turn of the 20th century, artists like Edvard Munch, Egon Schiele, and Pablo Picasso painted disturbing, surreal, and disorienting subjects. Many of their paintings evoked complex and contradictory emotions — or what Mendelsohn would call the “mixed sentiment.” It was as if they sought to explore Mendelssohn’s aphorism: “The horrible sight pleases. Whence this peculiar pleasure?”

It was as if they sought to explore Mendelssohn’s aphorism: “The horrible sight pleases. Whence this peculiar pleasure?”

Jewish painters also contributed to the development of this new sensibility. Maurycy Gottlieb and Samuel Hirszenberg painted scenes taken directly from the lived Jewish experience, which was often fraught, marginal, and impoverished. Hirszenberg’s 1899 painting, The Wandering Jew, which portrays an old bearded man stumbling wide-eyed through a forest of crosses surrounded by Jewish corpses, is deeply disturbing and grimly prophetic. Marc Chagall’s early works, particularly the portraits of his father, are rough and grim, almost hard to look at. Illiterate and poor, Chagall’s father hauled barrels of herring for his work. “My heart used to twist like a Turkish bagel as I watched him lift those weights and stir the herring with his frozen hands,” Chagall said.

This shocking modernist aesthetic drew strong reactions from nationalistic and fascist forces across Europe. Indeed, by the 1930s in Germany, modern art was seen as an act of aesthetic violence by the Jews against the German spirit. For Hitler, a man deeply influenced by physiognomic thinking, Jewish art was degenerate and ugly, reflecting a deeper degeneracy and ugliness in the Jewish soul. That most of the leading modernist painters were not Jewish didn’t matter: it was simply evidence of the extent to which Europe had been infected by an inferior race. This aesthetic philosophy was, in the end, entirely consistent, perhaps even predictive, of genocide. To rid the world of ugly art would require first ridding the world of Jews.

—

Given this history, to associate Jewishness with ugliness is, understandably, likely to upset, as the Vogue article surely did. Ugliness is a label that has been bestowed upon us by those who believe we are inferior. So, we now reject the label and insist on our own beauty! I understand the impulse, but I’m suspicious of it too. It is, I think, the same impulse that drives the fantasy of the Temple rebuilt. Or that led early Zionists to reject the figure of the weak European Jew and embrace that of the muscular and tanned chalutz. It associates Jewish pride and peoplehood with beauty. But, as Walter Benjamin warned, pursuing beauty as a political end inevitably leads to fascism. To this, Mendelssohn again provides a useful alternative. For him, the greatest benefit of appreciating ugliness is the humanizing influence such appreciation has on society. To make room for the ugly, which is always a form of alterity, allows us to see those who are different as fully human. It expands the circumference of our moral concern.

More so than in the paintings of the modernists, I see this idea exemplified in the photography of Dianne Arbus. Although she began as a fashion photographer, shooting pretty spreads for Vogue with her husband, at some point in the 1950s she gave this up and turned her lens towards those who she called “freaks:” tattooed men, twins, strippers, a woman with a monkey swaddled like an infant on her lap.

While some, including Susan Sontag, opposed the lack of beauty in Arbus’ work, others found it to be propelled by a philosophy similar to Mendelssohn’s. In 1967, after having seen Arbus’ first major exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, the art critic Marion Magid wrote: “Once having looked and not looked away, we are implicated. When we have met the gaze of a midget or a female impersonator, a transaction takes place between the photograph and the viewer; in a kind of healing process, we are cured of our criminal urgency by having dared to look.”

But if the photographs ignite humanity, it is not through pity. There is no moralizing. The perspective of her lens is usually darkly comic, melodramatic, sentimental — almost kitsch. Like her photograph of Eddie Carmel, a Jewish man who had a wild growth spurt in adolescence as a result of an inoperable pituitary-gland tumor. He stands before his parents in their living room, bending his head so it doesn’t hit the roof. His father appears to be looking at his son’s chest, unable to bear looking into Eddie’s face, while his mother cranes her head, almost in awe, to take in his full human form. If you look closely, you can see a picture of Jerusalem hanging on the wall behind them.

—

I learned the Torah portion for my Bar Mitzvah in a room that looked very similar to the Carmels’, in a house that was not very far away from Golds Judaica shop. The house belonged to Mr. Bro, a tiny man with a long white beard who also taught my dad his portion of the Torah. The parsha I had to learn was very long and boring, but it did include a repetition of the Ten Commandments. We’d sit and learn, and then, an hour in, we’d both get tired and need a break. Mrs. Bro would come in with a little silver tray carved with many little stars of David on which she carried two Cutie Pies, ice cream treats that have no dairy in them so you can eat them, kosher, after meat. We’d sit in silence and eat them slowly while gazing at a Chagall print that rested on the fireplace. Next to it was a classic silver menorah, and there, clinging to it, was a tiny little toy Koala, like a totem of my intersecting Jewish and Australian identities.

In fact, the phrase that inspired this essay, the Jewish Ugliness, is actually borrowed from an Australian architect named Robin Boyd, who, in 1960, wrote an essay called The Australian Ugliness. It was a screed against the decorative kitsch of Australian architecture, or what he called “featurism:” the way an Australian coffee table in some hotel might be shaped like a boomerang. The way plastic flowers adorned the windowsills of suburbia. As Boyd saw it, all of this ornamentation was more than just an attempt to beautify, it was a colonial reaction to a landscape terrifyingly alien to the European sensibility. In the colonial imagination, just beyond the last tendrils of suburbia lay a dry, fiery interior that had to be covered up and ignored at all costs. Trying to make everything pretty ended up making Australian design, for Boyd, very ugly.

Boyd wanted to make Australian cities less ugly. And if you look at the houses he built, in a way he succeeded: they are sleek, simple, elegant. Yet, there is nothing about them that seems to be responding to the Australian landscape. They convey mostly mid-century modernist sensibilities superimposed in a new environment, totally transportable — they would look beautiful anywhere else in the world. By contrast, the ugly Australian design Boyd lambasts is uniquely Australian. Its features stick out and feel aggressive and out of place. Encountering this ugliness elicits the mixed sentiment Mendelssohn describes — complex emotions that bring up guilt, shame, horror, humor. By doing away with the Australian ugliness, Boyd was also, in a sense, trying to cover up the violence and ugliness of the Australian colonial project.

The Via Maris pastel menorahs and vape pen mezuzahs do something similar to Judaica. They try to cover up ugliness but in so doing also gloss over a fraught history. A gaudy menorah might not fit within a certain minimalist, vaguely Bauhaus aesthetic that is supposed to be aspirational, but it evokes a mixed sentiment and points to contradictions that exist within modern Jewish identity.

Of course, the historical conditions under which the Australian ugliness and the Jewish ugliness arose are extraordinarily different. One is a story of colonial invasion the other of constant, diasporic wondering. But there is something similar between them; an out-of-placeness, a sticking out. For Australian settlers, it is born of arriving somewhere that is not home, and trying to make it so with a sense of shame and terror. For the Jew, it is this experience repeated endlessly, though with a sense of anxiety, of being chased. Perhaps this is why the most quintessentially Jewish Ugly object, for me, is the fully dressed Torah. In a velvet tracksuit and jewelry and a fancy crown, dressed up and ready to go anywhere, it looks out of place, kitsch, and strange — but unmistakably Jewish.