The first time I went to Boyle Heights I was searching for a temple — that is, a “labor temple,” as union halls used to be known. I had decided to write my dissertation about the Los Angeles Jewish Bakers Union Local 453, one of several Jewish unions with headquarters in the neighborhood, and set out to visit, hoping that I might glean some new understanding of the bakers by communing with the spaces they once frequented. I stopped at members’ former homes and the sites of the bakeries where they worked and then made my way from Cesar Chavez Avenue — formerly known as Brooklyn Avenue, the neighborhood’s main commercial thoroughfare — to the address I had for the Bakers Union Hall on East First Street. But instead of a labor temple, I found something else: the towering walls of the Interstate 10 freeway.

The 10 was one of five major freeways built in and around Boyle Heights after the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) surveyed the area in 1939 and declared it to be “literally honeycombed with diverse and subversive racial elements,” branding it with their lowest red ranking. Such evaluations were made as part of a Federal Housing Authority initiative to develop national standards for unwriting mortgages in the 1930s, a practice known as redlining that systematized racial segregation of Black and brown neighborhoods across the U.S. The diversity that the HOLC identified in Boyle Heights to justify its redlining was itself the byproduct of practices of exclusion: amidst the city’s rapid expansion in the 1910s, real estate developers began including restrictive racial covenants in their mortgage agreements that prohibited buyers from renting or selling their property to people who were not “persons of the Caucasian race.” Boyle Heights was one of just a handful of neighborhoods in Los Angeles that was not governed by such a covenant and became home to dozens of diasporic communities from all over the world, including thousands of Eastern European Jews, as well as Mexican, Japanese, Russian, Greek, Italian, Turkish, and Armenian immigrants as well as African Americans. It was a place where they could claim spaces of their own to imagine, debate, and realize their own forms belonging.

But the area’s kaleidoscopic diversity was viewed with suspicion and contempt, the HOLC’s description reflecting long-held attitudes about the neighborhood and the “detrimental racial elements” that resided there. As with other redlined neighborhoods, the agency’s devaluation of Boyle Heights caused home prices to fall, made it nearly impossible to obtain mortgages, and induced the local, state, and national governments to seize large swaths of land in the area to use for more “public” purposes, including the five freeways and the snarling East Los Angeles Interchange that connects them. The construction alone displaced over 10,000 residents and prompted others to leave the neighborhood en masse, initiating what former residents describe as the “exodus” of the Jewish population.

The site of this grassy embankment littered with trash fit neatly within this “exodus” narrative: the members of the Bakers Union, like other Jewish residents, were pushed out of Boyle Heights, their vibrant community life displaced by racist urban planning policies, their temples paved over by freeways. My own research about the bakers belied such accounts. Many had purchased homes in more affluent, white suburban developments elsewhere years before the neighborhood was redlined. I knew that while residential discrimination had been part of the reason that Eastern European Jews settled in Boyle Heights, their skin color also afforded them a degree of social and economic mobility that their Black, brown, and Asian neighbors were denied, that the racial borders that came to encircle the neighborhood were more porous to Jews than many of the area’s other racial others. But at the time, I took comfort in thinking that the bakers’ flight from Boyle Heights was the result of forces beyond their control, the absence of their union hall affirming a simpler narrative of destruction, marginalization, and loss.

—

We went to Bykhov (Bychaŭ, Быхаў) in search of a temple. I was travelling with a group of students and artists as part of Yiddishkayt’s Helix Fellowship, an immersive exploration of the literary, folkloric, and political traditions of the Jewish populations who inhabited Belarus and Poland for hundreds of years before the genocide and devastation of the 20th century. Bykhov was one of dozens of shtetlekh we visited, its history representative of one of several patterns of Jewish settlement we observed throughout the trip. Located on the banks of the Dnieper River, Bykhov was a “fortress town,” a strategically-important military outpost since the fifteenth century, with a large stone castle still visible today. Jews came to Bykhov to trade at the outpost, and, when they settled there in the 1640s, constructed a “fortress”-style synagogue to match, complete with a tower on one corner with small windows that look like gun turrets. By the late 19th century, when Jews comprised about half of the town’s population, it was one of eight synagogues in the town that, along with a Jewish printing house, several Jewish bookstores, and religious schools, comprised the infrastructure of Jewish community life.

Although Jews began leaving Bykhov years before, some 5000-6000 Jewish residents, many of them refugees who fled east, remained when the Nazis arrived in 1941. The Nazis executed 250 Jewish men in a ditch within days of their arrival and forced the rest of the Jewish population into a small ghetto near the castle where they were held for a week, without food or water, before being marched into the Maslovichy forest and killed. Only a handful of Jews survived to see the town liberated by the Red Army. After the war, they worked with diaspora organizations in the U.S. to raise the funds necessary to bring the bodies of their murdered families out from the forest and rebury them on the grounds of the town’s Jewish cemetery, as survivors did in Minsk, Glusk, Rogachev, and elsewhere. But the fortress synagogue was left standing: it sits today in the center of a traffic circle, untouched since the 1940s, its fortified tower and exterior walls still largely intact.

We were escorted to the synagogue by a local reporter and the town’s mayor, who unlocked its decaying wooden doors and let us inside. A massive hole in the roof let enough light in for us to see the thicket of ferns that had grown up near the Torah ark carved into the wall, the remnants of the floral stone carvings that decorated the dome above the bimah in the center of the sanctuary, and the arched ceiling extending from the bimah to elegantly angular corners covered in moss. As with many of the other sites we visited during our trip, the experience was quite visceral: the musty dankness, the crumbling brick walls, the remains of dead birds strewn about on the floor — all served as reminders of the violence, dispossession, and destruction that haunted Bykhov and the other ruins we visited.

I had taken to touching the earth in these places, to rubbing the dirt between my fingers to connect somehow with the blood and the bones beneath the surface. I would imagine the people who had worked that earth, played in that earth, and then gasped their last breaths upon it, trying to make tangible the otherwise incomprehensible scale of tragedy and loss. But in Bykhov, as the sound of my traveling companion Anthony Russell softly singing the kaddish echoed off the crumbling walls, I found my mind wandering in a different direction: why is this temple still here? Did the residents of Bykhov recognize it as sacred ground, the vestige of a Jewish community that once thrived there? Or, was this temple serving as a proxy for the atrocities that occurred, left standing out of some sense of collective guilt or shame or, even, superstition? Who is this ruin for? What purpose does it serve, for this town, for this mayor, for this country? What narratives of the past is this fortress temple fortifying?

—

As I got deeper into my studies of the bakers of Boyle Heights, I started being asked to give tours of the neighborhood focused on its Jewish history. These requests came from a variety of civic groups, schools, and Jewish organizations, but almost every one included one desired stop: at the Breed Street Shul, once the largest of the more than thirty congregations located in Boyle Heights, the “Queen of the Shuls” in the neighborhood. Originally established as a traditional religious school for children in today’s Little Tokyo, the congregation moved to Boyle Heights in 1913 to build a towering new synagogue with a Mediterranean-style exterior of arched doorways, decorative palmettes, and bands of light and dark brick. Even though my research focused on Jewish radicalism and Yiddish culture, everyone who asked for a tour wanted to see the temple.

Part of the reason for these requests was that the Breed Street Shul had been the focal point of a massive community preservation effort. Having fallen into disrepair after years of neglect and damage incurred during a major earthquake in 1987, the building had been slated for demolition until a group of volunteers and neighborhood residents, led by the Jewish Historical Society of Southern California, came together to prevent its destruction. As part of their efforts to persuade city leaders to designate the building as a Historic-Cultural Monument, they initiated a citywide public history project, collecting a trove of oral histories, photos, and documents, and released a documentary called “Meet Me at Brooklyn and Soto” to boost their preservation efforts. In 1998, they welcomed first lady Hillary Clinton to celebrate the building’s designation on the National Register of Historic Places and announced their plans to transform it into a cultural, educational, and community center.

My own research would not have been possible without these efforts. But the more I learned about the neighborhood, the more uncomfortable I became with the narratives used throughout the preservation campaign to cultivate the state’s support. The documentary film “Meet Me at Brooklyn and Soto” (1996) opens with a voiceover of an older man who, in Yiddish-inflected English, describes, “Boyle Heights… was like a shtetl in Poland or Russia,” a close-knit Jewish enclave created by Eastern European Jewish immigrants who, “like fellow pioneers before them,” had first settled in the cities of the east and then “headed to California, the golden state in the golden medina.” Former residents of the neighborhood then offer nostalgic descriptions of its “heymish” Jewish atmosphere: fish and pickle barrels on Brooklyn Avenue, old men with long beards on their way to synagogue, and the sounds of Yiddish in the streets. Blending these familiar Jewish tropes with the mythos of the American frontier, the film casts Boyle Heights as a virgin territory for Eastern European Jews where, through their hard work and determination, they remade themselves as prosperous Americans. Comments about the neighborhood’s diversity serve to reinforce the film’s central premise: that Boyle Heights was a place where (and when) Jews were ethnic, immigrant outsiders in direct contrast to their integration into the white middle-class following the “exodus” after World War II. The calls for support at the end of the film link the decay of the Breed Street Shul to the loss of that authentic Jewish past; that if the shul were to crumble, so would the memory of Jewish life there.

As my colleague George Sánchez has noted, claims like this — that Boyle Heights “used to be Jewish” — insert the neighborhood into a problematic narrative of ethnic succession, sublimating significant disparities in experience with social and economic marginalization, civic abandonment, and police violence among the neighborhood’s current residents. At the time “Meet Me at Brooklyn and Soto” was released, over one third of the neighborhood’s residents, 95% of whom were of Mexican and/or Central American descent, lived below the poverty line. In the months preceding the passage of Proposition 187, a statewide ballot initiative that criminalized undocumented immigrants as well as the teachers, doctors, and faith leaders who provided them aid in 1994, Boyle Heights was subject to multiple immigration raids by the INS and featured in dozens of local news segments that served to generate hysteria about “illegal immigration.” Already widely recognized as a crime-ridden, poverty-stricken barrio due to popular depictions in films like “Stand and Deliver” (1988), the neighborhood was declared as recently as 2008 “the nation’s gang capital” in a special episode of Anderson Cooper’s CNN Presents. As such, its residents have been subjected to intense surveillance and militarized policing, resulting in brutal acts of violence including the fatal shooting of 14-year-old Jesse Romero by an LAPD officer just less than 100-feet away from the steps of the Breed Street Shul in 2016.

Claims that Boyle Heights “used to be Jewish” enable contemporary observers to project images of a poverty-stricken “ghetto” backwards in time, bolstering triumphalist narratives of Jews’ ascendance into the middle-class as natural byproducts of their hard work and entrepreneurialism. They obscure the fact that many Jewish property owners retained their ties to the neighborhood after “the exodus” of the Jewish population, becoming landlords for new waves of immigrant residents. And they allow Jewish Angelenos today to avoid reckoning with the ways they have benefited from institutional advantages and racial privileges that other diasporic communities who settled in Boyle Heights have been denied. As I continued my tours, I began to see my own implication, that by participating in these pilgrimages — of wealthy, white Jews from the Valley and the west side revisiting the “lost” neighborhood their families used to call home — I was helping to ritualize the problematic historical narratives my work sought to challenge.

After more than twenty-five years, the folks at the Breed Street Shul finally secured the funding they needed to realize their plans for the space in July 2021, after California Governor Gavin Newsom allotted $15 million in his state budget to accelerate the renovation. Their plans include basement offices for non-profits offering social services to neighborhood residents, a large performance space in the sanctuary, and a permanent exhibition that will “[tell] the history of Los Angeles immigration.” I was happy to hear the news but also suspicious of the narrative they deployed to leverage this amount of state support. Did they describe how Boyle Heights “used to be Jewish” in their meetings with government officials? Did they offer tales of humble Jewish immigrants who built a shtetl on the frontier? I wondered whether their exhibition will make mention of Proposition 187, of the INS raids in the 1970s and 1980s, or, more recently, of the separation of families by ICE. I wondered whether current residents of Boyle Heights would see their histories, cultures, and experiences reflected in the space. I wondered how many other preservation efforts in the neighborhood the money could have supported and whether other organizations would be invited to join the planning process. And I wondered if, once the building stopped being a symbol of loss and destruction and opened its doors to neighborhood residents again, Jewish Angelenos would still make their pilgrimages there.

—

Our tour of Babruysk (Bobrujsk, Бобруйск) included stops at several synagogues. Located at the intersection of regional railroads connecting Minsk to southern and eastern Belarus, Babruysk was both a major military outpost and a major trading center, particularly of lumber and wood. Its mercantile prominence later attracted the development of heavy industry, particularly during the Soviet era. Today, with a population of over 250,000, it is one of the larger cities in Belarus.

Jews played prominent roles in the lumber trade, as well as in related crafts, with several prominent and affluent families helping to support a vibrant and diversified Jewish community life. By the early 20th century, when Jews comprised about 60% of the population, there were more than 40 synagogues across the city of both Hasidic and Litvish traditions and it was home to several prominent rabbis and religious scholars. The city was a hub for the Haskalah and Jewish publishing, and, in turn, became a thriving center for the Bund and Zionist groups of both socialist and religious varieties. Armed Jewish self-defense groups affiliated with these organizations defended it from a series of attempted pogroms in the 1890s and through several years of bloody civil war which followed the 1917 Revolution. It was also the birthplace of writer Celia Dropkin; we stopped to read her poems outside a building that used to be her Yiddish school.

Over 14,000 Jews from Babruysk were murdered after the Nazis invaded in 1941, most by machine guns in trenches on the outskirts of their city. Owed to its strategic position and mass production facilities, the city was almost completely flattened by shelling and bombardment and the remains of ruined buildings still dot the streets today, including the façade of a brick synagogue with pointed arched windows that once belonged to a Jewish craftsmen’s guild. As in Bykhov, these ruins have been left untouched, overgrown by ferns and moss and brambles. But in Babruysk, the surviving Jewish community reconstituted itself after the war, forming a synagogue of some 1000 members as early as 1948. Two decades later, some 15,000 Jews called Babruysk home, although the population has fallen since then in part because of restrictions on religious observance under Soviet rule. On this tour, we visited not only the ruins of lost temples but also an active one: a synagogue and community center operated by Chabad just a block away.

Our visit was awkward, as had been other encounters with Chabad on our trip. We had been informed by our teacher, David Shneer (z”l), before we left about the organization’s cozy ties to oligarchs and right-wing autocrats in Hungary, Poland, and Russia, relationships forged in an effort to gain access to resources and influence. Chabad has deemed such efforts necessary to advancing Jewish communal interests such as protecting Jews’ physical security and freedom to worship, arguing that those concerns should be prioritized over “secular” disputes about democracy and civil liberties. But the willingness of local Polish Chabad leaders to engage with and, at times, defend right-wing nationalists has drawn the ire of other Jewish organizations and activists doing the work of reclamation in the region and who have spoken out against government efforts to distort and police the memory of the Shoah, particularly in Poland and Hungary. Chabad’s entanglements, critics argue, belie the organization’s “apolitical” stance and give sanction to nationalists’ efforts to rewrite history. We got a small taste of that in our own encounters with Chabad leaders: one sh’liakh in nearby Mogilev, where Tsar Nicholas II formally abdicated the throne in 1917, spent his presentation of local history ranting about how the Russian Revolution was the worst thing that ever happened to the Jews, while the rabbi in Babruysk insisted on detailing every one of the people who lived there who had ties to the Lubavitcher Rebbe.

But the Chabad center in Baybrusk was also the first (and only) place on our entire trip where we got to speak Yiddish with a Belarussian. While the rabbi regaled us with his tales of the Rebbe, a very kind, elderly man approached to inquire about us and our group’s leader, Robby, addressed him in Yiddish. He was reluctant at first, confessing that it had been years since he last spoke Yiddish and he wasn’t sure he remembered all the words for things, but he soon warmed up, his pace of speech accelerating until he was making the same kind of jokes about Robby’s accent that I had encountered in historical texts. We learned he had fled east when the Germans came and returned after the war; that he wasn’t religious as a kid but had started coming to the Chabad center in his old age and reconnected to Judaism. I could smell lunch cooking as he spoke and began wondering how many other elderly Jews of Baybrusk came to get hot meals here, to read books and study Torah, to spend their days chatting with friends instead of alone. I began to notice the books lining the walls and the photos of weddings and children and celebrations. Surely, there was something sacred happening in here, no matter how dubious Chabad’s affiliations might be.

Led by its Chief Rabbi, a thirty-something Israeli-born Chabad sh’liakh who didn’t speak Russian when he first arrived, the Jewish community of Babruysk has, since our visit in 2017, received funding from the United Nations Development Program to rebuild the ruined synagogue just a few blocks away from the Chabad center as a cultural heritage site. In the same years, Belarus’ despotic ruler, Alexander Lukashenko (“Europe’s last dictator”) has consolidated his power and repeatedly held massive war games with the Russian military on the Lithuanian border. More recently, he has stolen an election and arrested his political opponents, journalists, and thousands of Belarussians protesting in defense of democracy, subjecting most to torture, sexual violence, and humiliation in prison. He frequently trespasses in antisemitic tropes and, in July, charged that because Jews “were able to prove” the crimes of the Nazis, “the entire world bows before them.” I wondered what the older man we met at Chabad thought of these developments; if he was concerned that Lukashenko had ordered the closure of over 250 NGOs providing similar social services, claiming that they were “weapons of the West.” I wondered if he was troubled by the way that Lukashenko has recently been selectively holding and, at times, releasing, Middle Eastern refugees at the Polish border to generate a crisis and undermine his European critics. I wondered if these were the topics that he and other elderly Jews in Babruysk discussed over lunch at the Chabad center as they made their plans to restore the synagogue ruins.

—

After I finished my dissertation, Boyle Heights became the subject of national news. This time, it was not gang violence that attracted the media’s attention but rather heated debates about gentrification roiling the neighborhood. As elsewhere, developers had been quietly purchasing buildings and driving up rents for years, but in 2015 tensions escalated after several galleries, some of them owned by elite NY-based firms, opened in the neighborhood. Vigorous community protest ensued, led by organizations including Boyle Heights Against Artwashing and Displacement (BHAAAD) and Servir al Pueblo (Serve the People), as did vigorous disputes over tactics, especially after “FUCK WHITE ART” was spray-painted on a gallery entrance and resulted in a hate crime investigation by the LAPD. These debates about gentrification continue today and have even become the central plotlines for television shows including Netflix’s Gente-fied and Showtime’s Vida.

Around the time the galleries first began moving into the neighborhood, I got an email out of the blue from a man who had recently purchased a building at 2708 Cesar Chavez Ave. After busting open a wall, finding flyers in Yiddish, and googling “the Cooperative Center” (the only English words that appeared on them), he had come across my work about the Jewish Bakers Union. The building he was renovating had once housed the bakers’ second labor temple in Boyle Heights: their Cooperative Bakery, which I had visited years earlier but found boarded up.

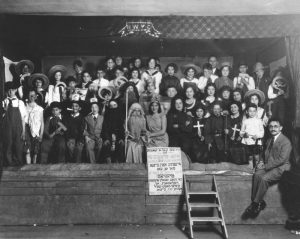

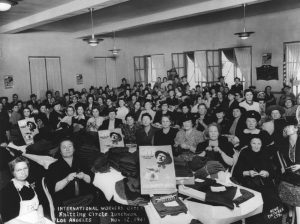

The Cooperative Bakery was originally established during WWI by a group of women seeking to lower the cost of bread by cutting out capitalist “middle men.” They served on the bakery’s board of directors, along with a handful of Socialist Party members, and employed exclusively union bakers, operating a wholesale distribution fleet of six trucks. In 1926, communist bakers in the union pushed to relocate the bakery’s operations to the Cooperative Center, where the Yiddish-language branch of the Communist Party had its headquarters, so that they could expand its distribution to the building’s café and large events in the hall upstairs. The bakery proved a crucial part of the union’s activism: they could offer jobs to out-of-work members and, during strikes, flood the market with union-made bread to bolster their picket lines. Through the bakery, the union members forged strong ties to other left-wing organizations and campaigns and became part of seminal interracial coalition-building efforts from which the postwar civil rights movement emerged. But, as a result, the bakery also became a target: it was violently raided by the LAPD so many times that the bakers filed, and won, a first-of-its-kind injunction against the LAPD to stop their harassment.

Amidst the crackdowns on “un-American activity” in the years after WWII, the Cooperative Center was sold off and became the Paramount Ballroom, a popular music venue and nightclub. The Paramount featured mostly Cuban, tropical, or Latin big band groups as well as special events and dance parties featuring local doo-wop and R&B acts, including those hosted by popular local radio DJ Dick “Huggy Boy” Hugg who broadcast the performances live. These dance parties were often interracial gatherings where Black, brown, and (mostly white) Jewish people danced, performed, and listened together, challenging the racially-segregationist housing and development around them. And from these types of venues, a distinct Eastside Chicano rock sound emerged in the 1950s and 1960s lead by bands like Cannibal and the Headhunters and Thee Midniters, and later Los Lobos and Tierra. In the late 1970s, after being closed for several years, the building became an underground punk venue called the Vex, hosting Los Illegals, the Brat, the Plugz, and Black Flag. After a concert-goer was shot outside during a concert, the venue was shut down completely and sat empty until 2011.

Around that time, the new owner of the building had first emailed me to see if we could talk about his renovation. As the battles over gentrification were heating up, he wanted to take his time remaking the space and reached out to me so he could be sure to properly honor the building’s history. Eager to finally see its interior, I said yes immediately and joined him for an hours-long tour. We had several conversations over the next few years as he slowly reopened the space, beginning with the ground floor where the bakery had been located. For several years, he rented the ground floor at a massive discount to a local Arts Conservancy, who used it to host computer classes and transformed the back area into a community radio station. I was invited several times to participate in, and to organize, events in the space as it opened up, thrilled to commune where the Cooperative Bakery once stood. And just before the onset of the pandemic, I joined the celebration of the grand opening of the club upstairs, which the owner had (re)named the Paramount Ballroom.

I thought about the bakers that night. I imagined the smell of the steam from the ovens, that sour-sweet aroma of yeast devouring sugar floating up to the second floor and mixing with cigarette smoke hovering over the chatter of radicals and revolutionaries. I imagined the speeches given, the friendships made and broken, the celebrations of victories, the grieving of failures. The fiery Yiddish that would have filled the hall. The sacred solidarity.

But as I sipped my $14 signature cocktail, I felt my implication creep in again. The bakers, I imagined, would have hated this bourgeoise fanfare, this trendy décor, this temple of consumption built in their space. They would have been furious to see that, included in the montage of images in the street-art style mural in the entrance hallway, was the logo of the Arbeter Ring (Workers Circle), an organization from which many of the founders of the Cooperative Center had seceded by declaring its leadership to be made up of “liberal and petit-bourgeois elements” who were enemies of the working-class. Was it my fault that that logo was there? Had I expected too much of the building’s owner when I described to him the intricacies of those rivalries and the tensions between Jewish nationalism and working-class universalism that animated them? Was this logo, painted over vintage concert posters, a sufficient gesture to the building’s radical Jewish past? Or had I, in my zealousness to amend the public memory of the neighborhood, given credence to some new version of the narrative that “it used to be Jewish,” now being leveraged in its gentrification?

On my way out, I imagined the members of the bakers union marching alongside BHAAAD, Servir el Pueblo, and other Boyle Heights community activists outside. I wondered what they might have shouted at me as I walked to my car, to drive an hour back to my affluent, white neighborhood on the other side of town. Would they have yelled, “Lign in der erd und bakn beygl!” (“May you lie in the ground and bake bagels,” or, in effect, “may you rot in hell”), one of the first insults I remembered from Yiddish class because it equivalates being a baker who can’t eat the bagels he bakes to spending eternity in hell? Or something more specific to the social dynamics of their upbringings, like “di gvirem fun shtetl zaynen ofgekumen” (“the gentlemen from the shtetl came up”)? Or maybe, as the new Comprehensive Yiddish-English Dictionary did, they would have opted to describe gentrification as“fargvirishung”?

—

That night, I also thought about the temple in Sejny, one of the last I visited during my time in Eastern Europe. Sejny is a small tourist town in northern Poland near both the Lithuanian and Belarussian border, surrounded by beautiful lakes and waterways first constructed in the Middle Ages. Sejny has, at various times since, been claimed as part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Prussia, the Russian Empire, Germany, Lithuania, Poland, and Nazi Germany. It has been sacked and pillaged and has been the site of armed uprisings against multiple empires and of multiple massacres. On the afternoon that Hitler invaded Poland in 1939, the town was bombarded and the entirety of its Jewish population driven out, never to be seen again.

The White Synagogue in Sejny was built in 1885 next to the town’s then-famous yeshiva. Animated by the maskilim who founded it to promote Jewish education in the area, along with a secular Hebrew secondary school that was one of the first of its kind in Poland. All three buildings survived the bombardment during WWII and, under the Soviet government, were seized and repurposed: the synagogue became a fertilizer warehouse, the yeshiva, a shoe factory, and the school, a post office. Then, in the late 1980s, a counter-cultural theatrical group seeking to recover Poland’s multicultural heritage settled in Sejny with the idea of creating a cultural center there. After years of negotiation and advocacy, they persuaded the local government to grant them custody over the buildings and remade the spaces as the “Borderland of Arts, Cultures, Nations” Centre in 1991.

When we visited the Centre, it was being staged for a performance later that evening, the towering arched white walls of the sanctuary lit dimly but elegantly by the concert lighting. There was an exhibition of local artists displayed on the walls and, in the corner, an art piece created by local school children as part of the Centre’s program called “The Sejny Chronicles,” designed to restore the missing intergenerational links in the town’s history. The students had created a reimagining of the town’s Jewish district in clay miniatures surrounded by tiny little books they had written in the voice of an imagined local resident. In the old yeshiva building, we visited the archives and library and the gallery annex, where several other pieces inspired by the town’s history were on display. In the school building, the evening’s performers were rehearsing what sounded like a blend of klezmer, jazz, and funk. They even let my traveling companion, Alexx, into the studio space upstairs so she could dance for a bit. It was a dream.

At the Centre in Sejny, the restoration of memory is deeply intertwined with cultural production. The region’s variety of folk traditions — Jewish, Romani, Balkan, Polish, and Lithuanian — are both revered and reimagined, mashed together with other sounds and influences to create something entirely new. I learned later that the Centre’s founders describe themselves as “animators of active culture,” a turn of phrase I find aspirational. The space they’ve created felt fresh, exciting, and alive in ways other synagogues we encountered in the borderlands did not. But there were also sights there that were all too familiar. The 6€ lattes in the coffee shop. The enamel pins at the register and yoga pads in the dance studio. The blonde guys with man-buns and beards setting up the stage for the night’s performance in tight black jeans. While it doesn’t really make sense to apply the word “gentrification” to a town of less than 10,000 residents, these were recognizable signs of some kind of transformation engendered by the “Borderland of Arts, Cultures, Nations” Centre. Or, at least, signs that doing the work of public history in neighborhoods with diverse, complex, and contested histories might implicate all of us in processes of real estate development, displacement, and erasure — regardless of our intentions.