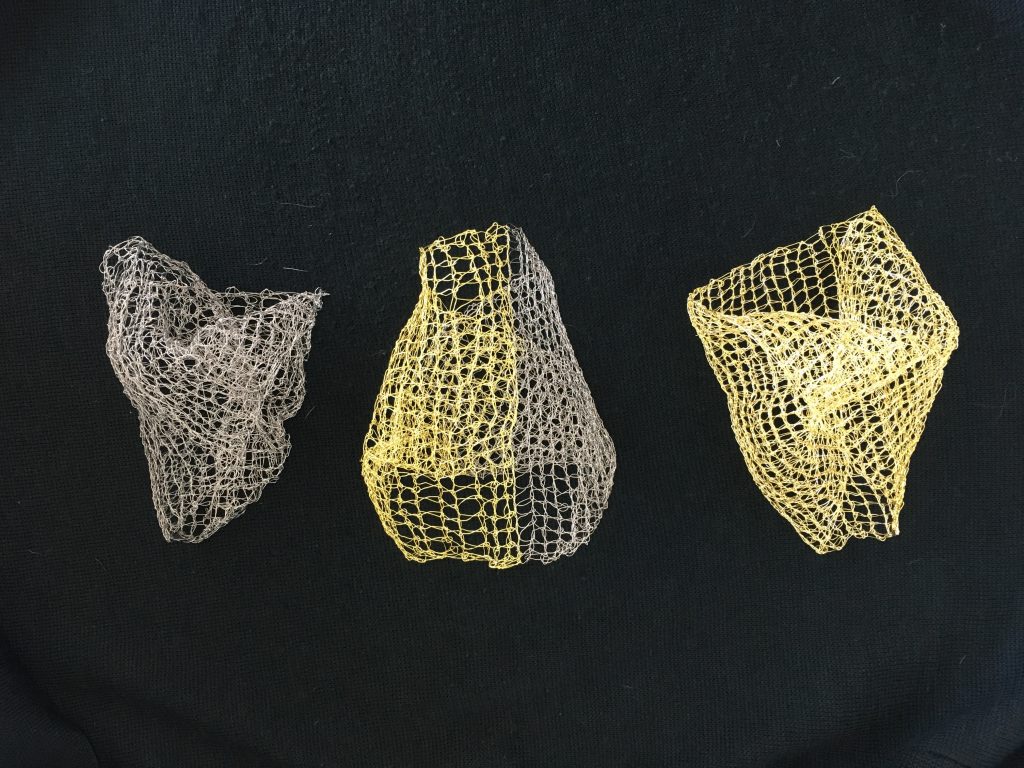

[Image description: Silver and gold wire wound, bound, and braided into three-dimensional structures, against a black background.]

Jacob Karlin: To begin, could you tell me what spanier arbeit is?

Lily Homer: Spanier Arbeit is a bobbin lace technique. It is the only textile technique that we know of that is exclusive to Ashkenazi Jewish production, and it is made out of fiber that is wound around itself to build up surface area. The wood jig that spanier arbeit is made on looks vaguely similar to the other jigs that bobbin lace is made on, but there are a couple of key differences including the way the bobbins are hung, and the use of gravity through that mechanism to hold the lace in place.

JK: And how did you find spanier arbeit?

LH: I read about it in 2017 in Ita Aber’s book, The Art of Judaic Needlework. I read it right after I completed my college thesis, which was in large part metal-based lace work. The description of spanier arbeit in Aber’s book is amazing. She mentioned that spanier arbeit is considered “unique” to Jewish production. The book included an image of it that I thought was beautiful, so that is when I started trying to Google around and found that there was not much information available about spanier arbeit.

Dr. Ann E. Wild of Freiburg, Germany knows this lace, and she produced some in Germany. She says she is only aware of two other people in the world who still work the technique on the original loom and they are both in Brooklyn — Mr. David Farkas and Rabbi Yosef Greenwald. Ita Aber is an American woman who makes this lace and is largely responsible for the growing body of more accessible essays and literature about it. I’ve tried to reach her but haven’t succeeded yet. And these are the only two women I know of that can make it.

It is not all that rare to see spanier arbeit around in Orthodox communities. I have probably seen it in shul or when I had an Orthodox bat mitzvah, since there were a ton of very fancy articles of clothing around but it obviously did not register. It wasn’t until I read that it was really important in a historical context that I started actually taking interest in spanier arbeit.

JK: So, based on the samples you’ve seen in person and online, could you describe what spanier arbeit looks like?

LH: Spanier arbeit is composed of various patterns: some people call one of the most popular styles of spanier arbeit “fish scales” because the pattern almost looks like semi-circles layered on top of each other in rows, and then subsequently copied up to make rows of layered circles. Spanier arbeit patterns are sometimes more floral. They exist as an embellishment, so the spanier arbeit pattern is usually attached onto the outside of a garment. For example, with skullcaps, they’re made into six triangles of various designs, and then those triangles are sewn together to make a kippah. The fiber used to make spanier arbeit is a pliable fiber, it is bendable, but it is not super bendable, so there is some limit to how you can wrap it around itself. It usually ends up being curved.

One other pattern is called Kasten, where spanier arbeit functions just as a border. Giza Frankel, in her book “Little Known Handicrafts of Polish Jews in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries,” lists the different kinds of patterns. Atara designs specifically are made of two main parts: the central design “mirror” (spigel) and the border “box” (kasten). A very common design was fish scales (liske). Others are: magen david, menorah, rosettes, stars, hearts (herzele), three snakes (drei schlangen), jug (kriegl), eye (oygele), leaf (bletl), and head (kepl). Different sects of Hasidim embraced certain designs over others, distinguishing one sect’s garb from another’s. For example, the Ruzhin design was a rosette and the Sasów design was heart shaped.

The actual physical form of it is symbolic. In order to make it, lace makers take these long, distinct fibers and wind them around each other. They will take hundreds, if not thousands, of feet of material, and condense it or contract it into a small surface area. The technique is about hiding the amount of material. Essentially, the lace maker tries to package too much of something, something that would not function alone as a decoration, into something that we can recognize as a surface area, by wrapping these materials around themselves.

JK: I’m gathering that there are a few metaphorical interpretations we can make out of that process. Now, do you know of the earliest example of spanier arbeit that exists? Do you know how old it is?

LH: The common belief is that there was a 13-year-old boy named Mordehai Leib Margulies, who fled the khapers (“catchers”) in Ukraine around 1830 and set up a workshop in Sasów, Galicia, which is now Sasiv, Ukraine, and produced what we consider the earliest example of spanier arbeit in Sasów, the one-time center of production. Before the examples from his workshop, I do not know, but it was thought to have been first developed earlier, in the 18th century. Margulies was making the atara, which is the neck band on tallises. I would guess that’s the earliest version. I’ve also seen very early examples of it on tachrichim, in which the neck band is decorated. So this lace does not exist on just the tallises, it exists on funeral smocks, women’s breast plates, waist bands, collars, bonnets, skullcaps, kittels, and cuffs.

JK: So what’s the role of spanier arbeit in attire? What purpose does this lace technique serve on the items you just mentioned?

LH: It is decorative. I think if you’re using it for a religious purpose, one could consider it as having a function, essentially intending spanier arbeit to be a part of any religious service. However, it literally serves a decorative function. It was originally pretty expensive, so it was for special occasions and probably only accessible to the wealthy.

Through all my exploration, I find a tension between this being an exclusive, religious technique, and this being a decorative garment covering. Is it sacred and controlled or is it a lucrative trade subject to changing styles and market demand?

The metals used in spanier arbeit, precious metals, oxidize over time. When they oxidize, they turn green and then they disintegrate. What’s left after the metals disintegrate is the cotton or wool core from the inside, so it looks quite odd. The older samples that have not been saved very well look like decomposing skeletons. They’re essentially half rope and half green metal. You know what the craftsmen intended to do, which is make this perfect adornment, but what’s really there is bubbling to the surface.

JK: What is the history of spanier arbeit production?

LH: The first spanier arbeit factory opened in 1830, and it was popular through the middle of the 19th century. However, by the early 1900s, it had somewhat faded from popular style. But it was still being made by the Shoah. The hub of spaneir arbeit production was in Poland, and 90% of Polish Jews were murdered. Let’s say that there were 200 people making this technique in Poland. That would leave 20 people who might have known how to make it after the war.

And how open are you going to be, after a trauma like that, about making Jewish crafts for Jewish consumption? Probably not very, right? There probably was a period where it wasn’t being made, but I know that it was able to travel outward from Poland, if in very small numbers. There are people who make it in Jerusalem and sell it in the markets there, and there are people who make it and sell it in Brooklyn.

Those are the two places I know it can be bought. But compared to what it was before the Holocaust, it is decimated. And even before the Holocaust, it was much less popular than it was at its peak.

JK: Going back to what you mentioned earlier about Ita Aber saying this craft was “unique” to Jewish production, could you elaborate on what makes this craft uniquely Jewish, and specifically Ashkenazi?

LH: As far as we know, it was invented by Jews in Eastern Galicia or what’s now the eastern part of Poland. It was made exclusively by Jews because they were able to keep it secret enough to maintain the technique. They were able to keep it word of mouth. It was sometimes bought by gentiles, but my understanding at this point is that the vast majority of it was made for other Jews for ceremonial clothing.

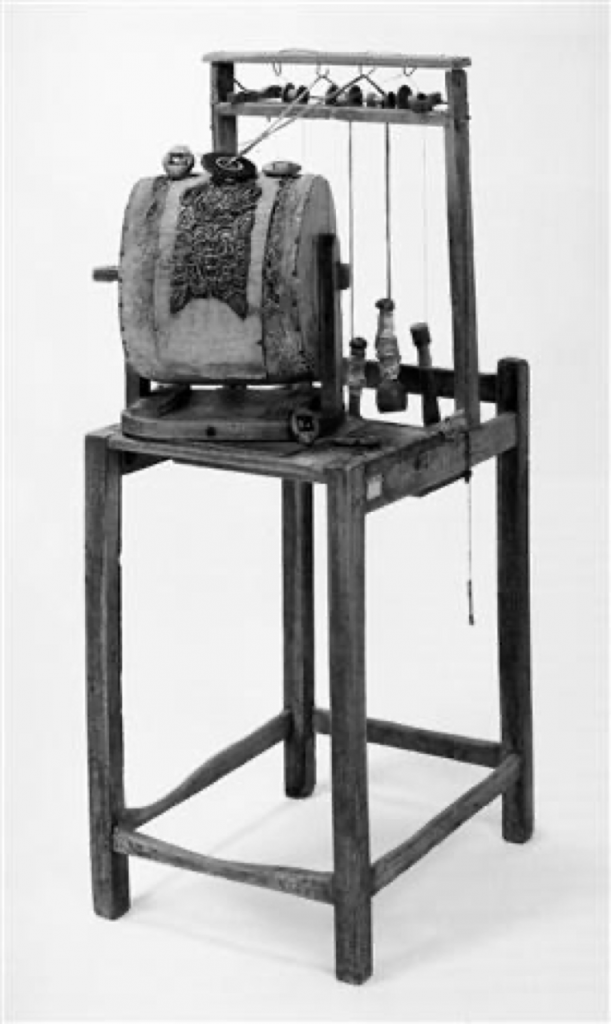

[Image description: A black, wooden loom for making spanier arbeit. The rotating drum sits on a raised platform and a frame for hanging bobbins is constructed behind it.]

I think the big wooden loom is a distinguishing feature as well. The process used to produce the lace is a big part of what makes it unique. This is also a reason I’m hesitant to simply look at samples of the lace and make up a way to reproduce it. The jig, with its big rotating drum, and frame for hanging bobbins, seems fundamental to its place in Jewish history.

JK: What differentiates spanier arbeit from other Jewish crafts?

LH: There’s a long history of Jewish metalwork. Jewish crafting on the Iberian Peninsula before the turn of the 11th century is a good example of a flourishing metalwork culture. I think other groups would commission Jewish handiwork, which helped this culture develop.

When I think of other Jewish crafts, I think of paper cutting, ceramics, and manuscript illumination –– very different types of media from metalwork. Like with similar techniques to spanier arbeit found in other cultures, there is a lot of overlap with these crafts as well. When small populations interact and share traditions, and since Jews migrated (forcibly) for thousands of years, there is bound to be stylistic similarities, if not duplications.

There’s also one style of architecture that is exclusively Jewish, which is the wooden synagogue. There were a couple hundred in Poland and they were all burned down in the 1940s. There are approximately 12 left, and they are all in Lithuania. The insides of these wooden synagogues are intricately painted. They’re full of color, aphid and floral and geometric designs on the inside, whereas the outside is a nondescript wooden building.The torah cover is very intricately designed and the door to the Torah arc is supposed to resemble the door to heaven.

I think spanier arbeit and all of these other examples fall into a category of intricacy. There’s a common thread of intricacy and detail in Jewish art, which speaks to the importance of craftsmanship: our labor over these objects can represent our commitment to G-d. Synagogues and metalwork are also materially opposed to paper cutting projects, which are gorgeous, but ephemeral. There is no expectation of longevity or permanence.

JK: Now moving our conversation to you, your history, and how you found yourself in this field of craft. Could you tell me what your relationship to craft making is?

LH: Craft production and professional artistry runs deep through my family history. My ancestors throughout Eastern Galicia subsisted through manufacturing textiles and furniture. My maternal great-grandmother, a refugee who moved to Chicago as a teen fleeing ethnic violence in Ukraine, left us her cyrllic diary, and I use that as a primary text in my studio. In that, she describes her process of Americanization in textile factories, Chicago streets, and American Jewish spaces. In another example out of many, my mother operated a jewelry business out of our kitchen while I grew up, and this is the same space where we said Jewish prayers over candles. In these ways, and others, craftsmanship is a major part of my cultural identity, and has always felt intertwined with my faith.

Also, I worked at the San Francisco School of Needlework and Design for a year and a half. Their mission is to keep embroidery from disappearing. Embroidery as a broad technique is less likely to actually disappear because it is super well-documented now, depending on which culture’s embroidery history you look at, but keeping it common practice is also important. We are not just trying to make sure it is written down somewhere. Making stuff together in a community is also important. And maybe not necessarily the exact techniques that we are doing but working with our hands together is something that we do not do very much now, and that I have learned to really highly value.

When I first read about this technique, I freaked out. In a good way. I’ve been in contact with some museums in the US that have been really helpful. The Ethnographic Museum in Krakow, Poland has samples of it, and they’ve been really responsive.

The Jewish Museum in Prague had an exhibition about spanier arbeit in 2009. So they were the ones that initially told me about a video that exists of someone making spanier arbeit, because the person who filmed their exhibition had brought it back to the US. As well, Dr. Ann Wild in Germany gave me some other resources to look at. She sent me some of her documentation, which was great, but which I cannot share because it is her private property.

I think a lot of ideas I am putting out there are ideas that post-war American artists worked with. A lot of themes I am working with relate to Eva Hesse’s work, and the topics of memory and forgetting. She was dealing with being ripped from her roots as a child of the Kindertransport. There’s this anecdote about her returning to Hamburg, where she was from, and how she tried to visit the home that she was deported from and the people who lived in the home wouldn’t let her in. But she never really spoke of the Holocaust in her work.

Another favorite artist of mine is Ruth Asawa. She was interned in California during the war, and after that horrific experience she made these incredible wire sculptures that are hollow porous forms that have these beautiful shadows. It is hard for me not to see her history in that.

[Image description: Red and white rope and burlap wound around copper wire. The wire is worked into stacked rows separated by a braid, making a circular, standing structure.]

JK: That’s fascinating! Of all the different types of craft making you mentioned, what about fiber art, specifically spanier arbeit, interests you?

LH: I have a vested interest in historical technical textile techniques beyond my goal to do anything with them. At this point of my research, I am now just as much interested in the metaphor of this work as the potential to learn it myself. The world of fiber art is a history of the world because every culture in human history has made fiber and we can see trade relations and we can see settler colonial tactics and we can see trade routes. We can literally see in which decades kingdoms existed based on the fibers and the fiber art and the textiles we find there. A lot of this information is just lost and a lot of it is not taken seriously as a form of historical documentation. Fiber art is not war. It is not directly government or politics. It is not as exciting in some ways. However, it can be. An important example is the Bayeaux tapestry, which depicts the Norman Conquest of England. We’ve been able to piece together that war because of this piece of cloth and that’s a very direct, literal interpretation of what I am talking about. But there are other examples: we only know about some of the early tools humans used because of the fiber samples we found.

Fiber art functions as a lens to see things through and it is so under-researched. There’s so much fiber art that exists that institutions undervalue like indigenous weaving techniques that were just either wiped out or disregarded and have thinned out. Those weaving techniques should be more valued. And then there are efforts to do that now — and those efforts are important.

I think we do not put emphasis on the cultural products that people make as a representation of humanity itself. Actually, that is what interests me most about people: the stuff that we make that reflects our resources and how we communicated with each other. And what we value. It tells us about the myths that we tell each other and the stories that we tell each other to be ok and what we do with our lives beyond just basic survival. But I also think about what happens when we forget these stories and what is lost when the stories stop being told.

When crafting techniques develop, disperse, gain popularity, fade, and disappear, what can we infer about the cultures those crafts come from? My suggestion is that the path of spanier arbeit implies the path of the Jewish people and drawing those connections is my ultimate goal. Ideally, I will present my research and artwork in the form of an exhibition featuring educational written text and sculpture. I do plan to build a compelling body of research and artwork, but I do not expect to find neat answers to my research questions. The value in our vernacular of our art histories do not lie in their clarity and concise meanings since they reflect us as individual people and we live complicated lives. The sculptor Vincent Fecteau, who my advisor introduced me to, said, “art is not about the thing itself, it’s about a desire or an aspiration about truth or meaning in a bigger way, and that the objects then that we make, are remnants of that search.”

My research has been about concealment and secrecy. It has never been about the beautiful samples I have been able to touch in museums (which has been wonderful). It is about that many of these pieces had been stolen during World War II and when repatriation efforts began the original owners were either dead or could not be found, so they were given to museums who could take care of these pieces. The work is about loss and how we then can carry on afterwards, it’s about seeking, and it’s about a failure to find what we’re looking for. It’s about the undulating and organic surface designs made by coiling and wrapping thousands of feet of fibers into something that looks small and utopian. A method of concealing what’s really going on or reshaping it into something we can understand. Covering and concealing: that’s what decoration is.

Very much related to spanier arbeit, and my studio art practice, is the thinking about interior design as a microcosm of our desire for stability. We design chairs, bedframes, room dividers, systems of government, city plans, machines of war, and we coat them in pretty things. Engravings, stained glass, fabric we inherited from people we loved, attractive talking heads on TV, mom and pop shops, and camo paint. We need to convince ourselves that what we made is worth it and good, so we decorate. And our decoration is aspirational. Upholstery is aspirational: it’s who we wish we were.

JK: I am aware that you encountered a few puzzling details about the history of the spanier arbeit lace technique. Can you speak to the ambiguity of the name?

LH: The ambiguity of its name was one of the first things about spanier arbeit that hooked me because I think documenting and sharing crafts in general, until very recently, was very much a word-of-mouth process. These crafts histories are not necessarily documented in a way that’s easy to interpret now. People did not record their techniques for posterity, so a lot of this research requires putting together bits and pieces of what we are able to find from the past. Even from the very beginning, searching for spanier arbeit proved difficult. For example, it was difficult Googling it in a spelling that I originally thought was just the only spelling of this one technique. Like, how many ways are there to spell a word? I would get one result and then I tried to spell it different ways, based on ways that one can spell different German words and pronunciations, and I slowly started getting different results. I then found that in modern German it is referred to as geftluchten. And if you look up geftluchten, which is an entirely different word, you get a different set of results that are much more modern. The geftluchten results show the spanier arbeit work that is still being done. Further, geftluchten is how it is marketed, so it lost its Yiddish term as far as I know.

Also, I need to mention that gefluchten in German means “cursed” and in Yiddish it means “fled,” but this is the word used in advertising. This is a point I need to discuss with a German or Yiddish speaker. Geflochten with an ‘O’ instead of an ‘U’ means “braided” in both Yiddish and German, which seems like the right word. And the Yiddish word “Gelochtene” means floral, which is sometimes included in online advertising as well.

The ambiguity of its name also reflects that we have no idea where it comes from or when it was invented or who invented it. Spanier arbeit can be translated in Yiddish to “Spanish work” or “spun work.” One theory about its origins is that it was developed in Spain before the Inquisition, over 600 years ago. And then after the Inquisition it moved with those Jews up to Eastern Europe. And then that is where it really took on as emblematic as the only Jewish lace work. But we don’t have any examples of it from before the early 1800s, so there is no actual evidence that it existed in Spain. There is no documentation of it in Spain, there is no writing about it, there are no samples of it, there is nothing.

So spanier arbeit can be translated into English as Spanish work and it can also be translated into spun work, which then, when some historian suggested that it was the latter, thought, “Oh, well, maybe because we can’t find samples of it from Spain, it actually just developed in Poland or Russia. It is intended to be translated as spun work. And it was invented in the early 1800s by Ashkenazi Jews.”

Furthermore, artistic techniques that can be traced specifically to Jewish invention are rare. This has to do with continuous forced migration and the mixing of ideas that come along with that. It is hard to trace cultural practices when its practitioners are moving and spreading out, being expelled, being excluded from the main consumer markets, or keeping their practices in secret.

[Image description: Gold played wire is wound and resting in a spiral. It attaches to a bouquet of wooden bobbins in the background.]

JK: Considering that immediate, linguistic obstacle to manage, how has the process been searching for spanier arbeit otherwise?

LH: While I’m Jewish, I’m very much so an outsider trying to learn about this, so no one answers my emails. When I do finally get someone who sells spanier arbeit in Brooklyn and I get to the point of it, which is asking them who their supplier is because I want them to teach me or I just want more information, it is absolutely shut down. No response. Or I receive a really hostile voice recording because the seller doesn’t want what they say to be in writing. Yes, there’s this barrier and I hope to build trust with people because I think the information is there. Understandably, they do not want to just give it out to someone they don’t know when they have had literally hundreds of years of success keeping it in the family. It is annoying for me to be talked down to, but I get it.

There are a lot of barriers in this research. Making spanier arbeit also has gender implications. Throughout history, women have been both included and excluded from this craft. Margulies’s studio initially hired exclusively men to make the lace, but eventually hired some women too. Now, it seems to be a male craft. Gender is a barrier in my research. Spanier arbeit is made by men and passed down to sons by word of mouth. And sons usually undergo a sort of apprenticeship. This is not for women, though this was not always the case. So a woman asking to be taught it by a craftsman in Jerusalem, an American woman especially, is not necessarily alright with them.

Further, there is a difference between seeing it in a collection or historical institution and seeing it actually being used and sold. The places I’ve seen it are in private museum collections where if I take pictures, I can’t post them, which is another cultural barrier to sharing this technique more broadly. A lot of pieces either come from people, private donations from families from before the war, what people could salvage or what they inherited, or in repatriation efforts. If the family can’t be found and it is taken from a Nazi home then it is given to a museum. So that was the context I originally saw it in. Essentially, I saw spanier arbeit in a historical bubble where it is kept super secret: make a contact, make an appointment, see it for a couple of minutes, don’t share pictures. The way that it is being made and sold on websites with other machine-made Judaica, although it is physically the same, it is not the same as understanding it as a historical item.

I should also be clear that the museums I’ve connected with for this research have been wonderful and generous with their resources and time. Bonni-Dara Michaels, Collections Curator Yeshiva University Museum in New York, and Tom Gengler and Kathleen Bloch at Spertus Museum in Chicago, in particular. Also the Ethnographic Museum in Krakow, POLIN Museum in Warsaw, and the Jewish Museum in Prague, to name a couple, have helped me and continue to help me.

JK: And why do Jewish craftsmen and those who know the process of making spanier arbeit keep the technique secret?

LH: Everyone’s watched Fiddler on the Roof: tradition. What connects us, like the acts that we do every year, is what has connected us for thousands and years, and those are really sacred. What you’re saying in one synagogue in Pittsburgh on Rosh Hashanah is the same thing that they’re saying in Lodz, Poland.

By researching spanier arbeit and by reaching out of my lane to learn more than is given to me outright I’m messing with the traditional process of passing on heritage by word of mouth from generation to generation. But we do this all the time without realizing it. The way I perform rituals on the high holidays is so entirely different from what my ancestors were doing even a generation or two ago. I’m aware that I take what I want from my faith tradition and I leave behind what I don’t find useful. This is probably a result of living in America where the culture is: see shiny thing, take shiny thing, with little regard for where it comes from or who it’s meant for. And I think that is probably heretical according to common interpretations of Jewish tradition, or rather, there are many aspects of Jewish culture that are purely sacred and intentional, which I and other Jews I know use casually.

I think Jews have a lot of reason to keep things close to the chest. And I think spanier arbeit is more of a profession than an art. A good analogy for spanier arbeit is a restaurant chef with a secret sauce. If you have something that you know is valuable, why would you want to give it up, especially if the people who you would be giving it to have shown you over and over again for millennia that what you have, essentially, they don’t want to be yours, they’ll take it from you if they can. Or even, when you think you’ve made friends with someone different from you, you have been duped.

Additionally, from a business perspective, it’s more profitable to maintain the process of making it. But also, there is a component of secrecy and concealment in Jewish culture that is expected and, I believe, ingrained. There are a lot of components of the faith itself that are controlled by who can know what and who can do what. The Kabbalah, for example.

JK: Lastly, and I guess most importantly, why is spanier arbeit important to you as a research subject?

LH: This is the crux of what I am doing: I am trying to explain why this is an urgent project. It is important that crafts do not die. But I want to note that we let parts of our cultures go all the time and we often pick and choose what we want and we forget what we do not want.

When I heard that spanier arbeit was the only Jewish textile technique, that registered in my head as being worth investigating. It was important to investigate because from what I experienced growing up, and what I’ve read about, the amount of physical culture that is actually exclusive to the Ashkenazi Jews is very limited. This is because when our ancestors were allowed to stay in one place for an extended period of time, meaning more than 100 years, they were relegated to areas with very little resources. They were also adapting to the cultures that they were shoved into. So, a lot of their artistic products were developed from those cultures. There’s this confinement and limitation. I think that we’ve done with it what we can, but when I hear about something that’s actually unique, I get excited.

Also, because there are so few of us and spaneir arbeit is supposed to be kept secret, it is constantly at risk of just not existing anymore. If no one documents it, who’s to say it will continue to exist? Maybe it is a popular enough product that the people who are making it would just keep passing it down, but that doesn’t seem very likely to me because crafts go out of style.

Another aspect of spanier arbeit that interests me is its unattainability. I can see spanier arbeit exists in very guarded forms. I know it is still being made, but I’m just grasping at a sort of spanier arbeit-shaped ghost and this impossibility and almost sure failure is fascinating to me. It does not discourage me. I am now just as much interested in the metaphor of this work as the potential to learn it myself.

Something I have come to realize, which I have had a hard time coming to terms with, is that I do not actually think I care about the technique itself. Rather, it matters to me that it exists because I think it is beautiful and it symbolizes something important. The relationships around it and the path that it has taken are important. The biography of spanier arbeit is parallel to the biography of the people who made it and who perpetuated it and who are allowing it to disappear, so it is more what it represents than what it is that I’m holding on to.

And I’m seeking these ideals, which is this “closed loop” and perfectly objective understanding of what happened. I know simultaneously that even for things that we have very clear documentation of, that documentation does not really reflect what happened. Rather, that’s what someone said happened. If I were to document something, I would have a very biased, fractured perspective of what happened. For example, I would write a really inaccurate history of the morning I’ve had until this interview where I got up, brushed my teeth, and had a coffee.

Lastly, as a diasporic Jew, I feel rootless. I have no clear picture of the road my ancestors took, I only know that they were pushed from place to place. Various documents place my ancestors in Belarus, Poland, Russia, Lithuania, and Ukraine. Shifting borders in these areas make personal accounts unreliable. For example, my grandfather, who spoke Yiddish but never spoke of his childhood, at least when I asked, would always offer a different answer when I asked where his parents emigrated from. I think this was out of a wish to forget, but knowing him, this might have been bait so that I would also seek out the answers myself.