I, too, have often thought that Israel is not Jewish enough.

In the sense that it lacks sensitivity toward the stranger, the orphaned, the widowed; in the sense that it does not leave the land fallow in Jubilee years; in the sense that it does not prohibit usury and interest; in the sense that it is not multilingual and Yiddish, Judeo-Arabic, and Ladino are not amply heard; in the sense that our children in the state education system will not learn enough about Jewish creativity in exile; and in the sense that the East (Mizrach) will continue to be repressed, hidden, denied, and ridiculed, and Jewish-Arabic culture will continue to live in exile.

Meir Buzaglo, a philosophy professor at Hebrew University, has often said that Judaism was caught unawares by statehood. Thus, for example, halacha still does not ask how a Jewish state should function on Shabbat, as a modern state in need of electricity and hospitals on the seventh day of the week. Halacha remains oriented from the perspective of a minority-Jewish community living within a non-Jewish majority. The Jewish texts that once sought revenge against oppressive non-Jews—written as a Jewish minority’s sublimated symbolic revenge against an oppressive majority—change their meaning when adopted by a majority-Jewish society ruling over others. Judaism has still not asked the meaning of justice in the framework of a modern state, or about the distribution of wealth and exploitation in relation to a neoliberal economy (unlike the communal framework of tzedakah).

We still face a lengthy battle over Judaism’s character. Our Judaism, to put it simply, has been stolen from us for more than a century. In fact, it has undergone a series of severe reductions. Secular Zionism reduced Judaism to a state and sovereignty, and sought to cleanse itself and its Judaism from any trace of the “diaspora” or the “East,” considering them contemptible and inferior, respectively. Haredism, meanwhile, has reduced Judaism to halacha. Religious Zionism has reduced it to territory. And Israeli-Jewish life has reduced it to Holocaust remembrance—remembrance that sometimes blurs whether the perpetrators were Europeans or Arabs. Nonetheless, its primary conclusion, it seems, is that we need a strong army. And it is incumbent upon us to hate those who do not enlist in that army, whether Haredim, Arabs, or leftists. (This hatred is meant to ensure an “equal burden,” as if we have already achieved sufficient equality of the burdens of poverty, inadequate wages, and life in the country’s periphery.)

Practically speaking, the first thing many—if not most—Israeli Jews will answer—with little to no shame—when asked about what constitutes the Jewish identity of a place is that it must be free of Arabs: a home free of Arabs, a school free of Arabs, a city free of Arabs, a government free of Arabs, a dreamed-of state free of Arabs. One might look at one’s Jewishness and remember that things used to be otherwise, wider, and might demand something different in its name. But by now one can no longer be sure that such a Jewishness remains.

There are many more matters for us to clarify: what is the meaning of a Jewish state in the Land of Israel when the Messiah has yet to arrive and the age of exile established for us by HaKadosh Baruch Hu has not yet ended? Is the modern political concept of sovereignty, upon which secular and religious Zionism are based, congruent with Torah and halacha’s grasp of our belonging to the Land of Israel or of the Land’s belonging to Hashem? Does the Land of Israel belong to the people of Israel or the other way around? Do those whom the Master of the Universe chose to live here in our place not merit collective rights by virtue of the fact that He did not annul his choice that they live here?

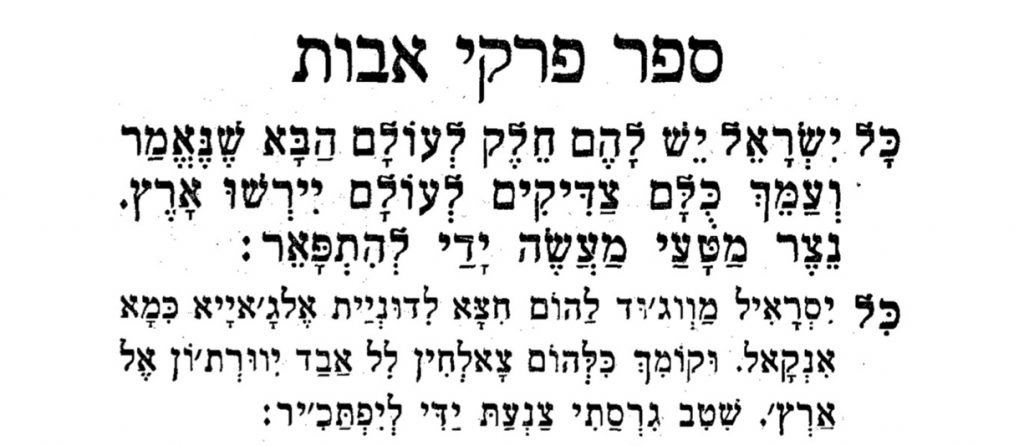

The struggle over our Jewishness and its definition remains quite long. We must re-learn the tradition of Mizrahi Judaism that has been erased, and the Jewish-Arab and Jewish-Muslim symbioses. We must continue opening up the study of sacred texts—including the Gemara—to women. After several generations in which those who defined themselves as secular (and with them the entire secular state education system) deserted Jewish texts written from the Tanakh to the Palmach, and after several generations in which Orthodoxy monopolized these texts, recent decades have brought many to learn Gemara anew, to interrogate the debates of the Bavli and Yerushalmi, to move between aggada and halacha, between Hebrew and Aramaic. (It goes without saying that within the secular-religious dichotomy, the “traditional” is erased and the opportunity to choose an alternative, complicated relation between ritual, text, and context is foreclosed.) I hope we witness a similar revival of Yiddish, Judeo-Arabic, and Ladino.

And yet, the Jewishness of the state, according to those who passed Israel’s nation-state law, does not mean the study of Aramaic within the state school system, or the study of Judeo-Arabic, Yiddish, and Ladino in religious state schools. As far as they are concerned, as are likely the sad majority of Israelis, a Jewish state is an “Arab-free” state. For those who passed the law, it will secure their right before the High Court of Justice to legislate the segregation of communities and budgets for the Jewish majority, while ensuring that only the Jewish majority can decide the future of the state and the future of Judea and Samaria—which, it so happens, is home to a non-Jewish majority.

And so our Jewishness, like our Mizrahi-ness, has been taken from us and reduced to racism, segregation, and phobia. If the state is to become more Jewish, it must become more just, more Arabic, more Muslim, more Mizrahi, more Haredi, more traditional, more humane.

A version of this text was originally published in Hebrew in Mekomit.

Translated by Natasha Roth.