I.

“Everyone take out your IDs! No entrance will be allowed into this building without an authorized form of identification.”

A student wearing a camouflage uniform at the main hall entrance of Goldsmiths, University of London, yells the above to a group of disinterested undergraduates on a drizzly Tuesday afternoon. It is part of a protest action taken by the university’s Palestine Society, designed to simulate the excruciating process that Palestinians go through on a daily basis when crossing checkpoints from the West Bank into Israeli territory. This action attempted to inflict pain through inconvenience in order to transmit the trauma of routine violence, fantasizing that the British student going into lectures and seminars might experience something of the strict mechanisms of the Israeli occupation at work.

I recall standing in the entrance of the building, noticing passers-by hastily walking in and out of this space. The “soldiers” got more aggressive with their commands. Their voices echoed through a megaphone to the streets. I stood hesitating and contemplating the role I was to assume; was I to pretend to be the Palestinian subject, being inspected by the make-believe Israeli soldier? Or was I to be the soldier that Israel groomed me to be? I walked into the building, wishing both to pass unbothered and to cause a scene, but I changed my mind and retracted. I understood how unfulfilling this performed protest was. The privilege of choosing between walking past the soldiers or using a different entrance is one I decide to use, and with that gesture, the demonstration felt lacking — not because the violence they were trying to unpack was unimportant, but for a lack of account for the ways the excessiveness of such a violence already flowed complexly through the subjects crossing that imaginary checkpoint.

The Israeli soldier’s competing mythologizations reveal a stock imagination about dominant power and authority; almost always a he, the soldier is viewed as either the vicious executing arm of an apartheid regime or the angelic disciple of Zionism. The Palestinian, as the soldier’s negative image, similarly lacks voice as either the subordinate body or, in certain Zionist fantasies, as vicious monster. The student role-play invoked a dichotomous understanding of these power relations but withheld the erotic anxiety and pleasure that such a relation induces. Sex, our psychoanalytic and poststructuralist critics remind us, is always entangled with violence. The members of the Palestine Society might have played their part as the oppressive soldiers, but the spatial surroundings failed to recreate the feelings of suffocation and human density that characterize life under the occupation and the theater of checkpoints specifically.1

In his groundbreaking History of Sexuality (1976), Michel Foucault stressed that power and sexuality are neither things that can be held nor conditions from which we can be ‘liberated.’ Violence, and attempts to dominate, always operate in an existing field of power relations. And these relations are also always imbued with the sexual charge of their potential switchability. It may seem unethical to project sexuality onto a situation so inhumane. To interpret a sexual charge in relations between the Israeli soldier and occupied Palestinian seems to reinforce (and efface) the interpreter’s position as a detached onlooker securely in power. But power is not so easily given and taken; sexuality is only missing from this terrible scene if we eliminate the victims’ own complex, innate sexuality purely on account of their victimhood — reduced, essentially, to the status inflicted on them by the Israeli state. I am suggesting that we see more than the sexual charge of Israeli racism in this moment of brutality by also recognizing the beginning of a sexual relation whose traumatic afterlives complicate neat positions of choosing pleasure or pain. This essay is not about a Palestinian reclamation of sexuality, nor is it about a conflict that can be resolved. It instead traces the way a few Israeli subjects have represented their own processes of grappling with the intransigent conditions of violence from which Israeli and Palestinian subjectivities inevitably take form.

II.

In Sigmund Freud’s “A Child is Being Beaten” (1919) the psychoanalyst attempts to understand sadomasochism in three stages. The first stage occurs in early childhood, when a child witnesses a sibling being beaten. Feelings of jealousy and rivalry arise and point toward sadistic pleasure, as the person beating the child is recognized as the father figure. In the second stage the child identifies himself as the beaten child, turning toward masochism. Freud scholars debate whether this is primal or perverse. Regardless, Freud felt these first two stages resulted in a conscious third stage of aroused daydreaming and masturbatory fantasy that displaces and re-enacts the traumas of the first two; a mass of unknown children is beaten, punished, or humiliated by a father figure often embodied in the teacher, police officer, or soldier. These figures of power bring scenarios in which the fantasizing child transforms unpleasurable feelings of guilt, humiliation, and degradation into sexual excitement.2

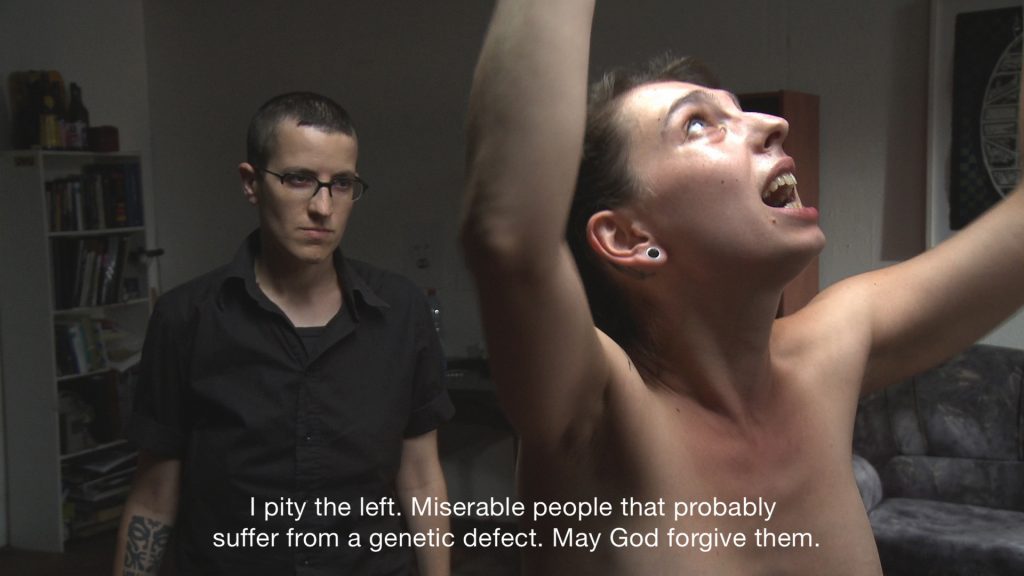

This excitement is notable because it is linked to trauma and the blurring of our fantasies and realities — a terrain that contemporary artists have been exploring to develop an alternative kind of ethical witnessing. Roee Rosen’s 35-minute video, Tse (Out), 2010, begins with an interview of two Israeli women who are positioned to stand in opposition to one another; one is identified with the extreme political right, the other with the radical left. In a reversal of conventional attitudes amongst the left in Israel, in which the right is imagined with all the power, the woman on the political left is a dominating top while the other on the political right is a submissive bottom. Both are experienced S&M practitioners. The top says:

“Our society is premised on oppression and power, so I believe these are also the building blocks of our fantasies. All the generic BDSM fantasies go there, be it the classroom, with a teacher, be it something military, be it parents, in fact all the places where the super-ego reigns supreme. So I think it’s very transgressive to use these oppressive building blocks and build from them something new out of choice.”

Social oppression is often omitted from psychological theories of sadomasochism. But the subject who has been battered again and again can, through sexual play, transform unpleasure into the ultimate form of pleasure. As John K. Noyes has argued in The Mastery of Submission: Inventions of Masochism (1997), one can even challenge the relationship between subjectivity and stereotype by performing the degrading stereotype in a controlled environment that provides elaborate rituals for the subject’s remaking.

As the interview in the video progresses, it becomes clear that the submissive bottom is possessed. She has been taken over by the spirit of Avigdor Lieberman, an infamous politician known for his hyper-nationalist agenda and racist rhetoric.3 As the women meet, the submissive bottom is tied up and naked. The dominant top begins hard spanking and the terrifying spirit of Lieberman violently emerges from the naked, bruising body. Her possession by Lieberman signals that surveillance and state governance over bodies can suffocate to the point where a necessary process of exorcism is required to reclaim her body. Once the illness of nationalism and racism has taken over, a pain-enduring procedure is the only way to release a subject from the ironclad grasp of the state, allowing this unpleasure to slowly reemerge as desired, warm, and pleasurable — only until the inevitable need for the next exorcism.

I can relate to the sadomasochistic metaphors of subject-state relations suggested in Rosen’s video. However, there’s a clear difference between the consenting subjects in Rosen’s video and myself as an Israeli subject and consumer of Lieberman’s language. The rhetoric around sadomasochism often includes an emphasis on trust. The bottom has to trust the top to skirt around the boundaries of pain and pleasure, assuring the bottom that the top tends to the bottom’s durability with care and love that will surpass the pain. This trust and fluidity between the two bodies could work as a powerful metaphor for the relationship of national subjects to a law-abiding state, as submissiveness to the state’s sadism must bring promise of pleasure in safety.4

Though we do not know the outcome of Rosen’s exorcism, we do know about the continuing, unsustainable conditions of violence on the ground. From one perspective, Rosen’s video elucidates the limiting choices offered to an Israeli subject: to either follow the state or be complicit in its violence anyways, either getting off on its racism or on an ineffective critique of its racism. But the video also stages the mechanisms of this complicity — the idea that subjects are bound in a struggle for power — as if it is something one can grasp, a scene that we enter and remake.

III.

The speeches that come out through the exorcism — the murderous desire inside the body of the right — is the space in Rosen’s video where the Israeli state’s relationship with the Palestinian national subject becomes audible. Through Lieberman’s speech, we learn how Israel strikes brutally and repetitively, pulverizing Palestinian trust in continuous attempts to erase and deny their autonomy. But even as violence to the Palestinian people is made visible, the Palestinian subject is not. A recent exchange with a close friend made me reframe this problematic through Rosen’s lens: are Palestinian subjects the submissive bottoms in this equation of occupation; if so, can they be dominant subs, wielding the distribution of pain and pleasure?

My Jewish Israeli friend “Jay” shared a personal experience he had online, on the gay-oriented website called “Chatrandom.” The website matches two users in a simple algorithm that filters for nationality, revealing their faces or, more often, their torsos and crotches. Each user is assigned a flag, corresponding to IP address, allowing each to pick and choose national subjects with whom they wish to be matched. Some scholars, such as David Kreps, consider webcam chat “the most raw and unfiltered form” of online social media, empowering individuals to perform their own scripts to those who may not have consented. As Jay was randomly matched with a Palestinian Syrian user, the virtual and political merged in their cyber-performance of intimacy and violence:

“I don’t remember how the conversation began, but I always found it interesting, as soon as I see that a user is from Syria, Palestine or Lebanon, I send them a message in Arabic to catch their eye because I think, almost automatically, that they press ‘next’ when they see Israel. So I send them a message in Arabic to ask how they’re doing. That’s how we started the conversation and then at some point we got to the fun stuff. It was very interesting, I remember him feeling very excited by me. Soon into the conversation he wanted very specific things. Mostly that I, as an Israeli, will humiliate him as an Arab and Muslim. It was an integral part of the interaction. To me, there was a dissonance, as someone who is affiliated with the left — something that is a part of my identity; I believe in equality and not in racism and that is something that defines me. Suddenly, even in this virtual platform it was hard to take part in it, but I did. Even though it wasn’t real, and I knew I didn’t believe in it, it was hard, but eventually I was able to get into it — to become this humiliating persona, and not just any persona but one that is humiliating on the basis of race and is very racist. He wanted me to call him a dirty Arab.”

Syria has just over half a million Palestinian refugees living within it, the result of continued dispossession of Palestinian land and communities since 1948. Though the border of Israel and Syria has largely been politically quiet for several years now, internal politics have wreaked havoc within Syria, displacing millions internally and internationally. While the matter of the Syrian refugee has been in the headlines for years, bringing repeated attention to the Western fear of the Oriental other through a constant muddling of the terms refugee and terrorist, the existence of a queer Syrian subject, refugee or not, has been erased. In Jay’s session, the mythically-abusive Israeli soldier, the antagonistically super- and sub-human Jewish subject, the vulnerably unstable Muslim, and the punishable Arab all serve as major influences for fantasy.

In his essay “In You More Than Yourself” (2007), Marxist and psychoanalytic critic Slavoj Zizek offers another perspective about the use of social gatherings on the internet. He argues that “in the guise of a fiction, the truth about one’s self is articulated. The very fact that I perceive my virtual self-image as mere play thus allows me to suspend the usual hindrances that prevent me from realizing my ‘dark half’ in real life.” Cyberspace allows for the suspension of the constructed self, and calls upon us to play and expand it, revealing and reveling in the depth of the self’s multiplicity, as social as well as subjective truths emerge and turning an unpleasurable reality into pleasurable virtuality. Jay foregrounds his leftist politics as a major part of his identity, and yet so is his entrenchment in racist systems; in virtual space, he confronts the racialized discourse that makes his sexuality ‘dark’ in the first place.

When speaking with Jay, he acknowledges to me that the Internet created this unique borderless habitat for this sexual encounter, one that could not exist outside of an online space. Jay and his partner’s excessive imaginary could take form and become formless as desired body-nations and body-types became interchangeable and sexual role-play was explored in fantastical ways, controlling violence to stimulate uncontrollable pleasure. Jay continued:

“It was fun, mostly it was fun that what I was performing was really getting him off. Because I wasn’t in my element, it felt that I was getting instructions. It was often uncomfortable, the dissonance, to try and follow orders, to try and please him. But it was a challenge, trying to get into a character, to see if I wear it well. Which I think I did. It was mostly a challenge. I suppose that I am a very particular fantasy he had, seeing some superior conquering Israeli force.”

This performance is meaningful because of the multiple role reversals that occur within it. Beyond the subversion of sexual roles, a subversion of internationally and historically ascribed roles occur in a manner reminiscent of Jose Muñoz’s notion of disidentification: “Toxic identity is remade and infiltrated by subjects who have been hailed by such identity categories but have not been able to own such a label.” Jay feels dominated by the sub, coerced into pleasuring him by assuming a character with which he disidentifies outside of cyberspace. Jay gets pleasure like the top in Rosen’s Tse; except here, he forges a relationship not simply with an other but with another person maligned by the Israeli state, even as Jay plays the Israeli aggressor. As his Syrian partner assumes the role of submission in a very dominating and demanding mode, inhabiting and subverting his Orientalized queered sexuality by welcoming a hurling of insults and derogatory terms, he extracts the state racism that prescribes and proscribes Jay’s desire; Jay faces himself as the one he has been warned against.

We are often reminded that the Internet is massively oppressive, inaccessible, and divisive. But it is also a mixed bag of utopia and dystopia that, as Barbara Browning has pointed out, makes it ripe for sadomasochistic play. Cyberspace captures the virtuality of the sadomasochistic relation more broadly — of the absence and presence of physicality, of subjects who can flip the script. To re-own sexual and bodily experience, to redistribute pain and pleasure, echoes Barbara Browning’s argument that “sex is always more psychic than physical.” In sadomasochistic play, senses are heightened as both the mind and the body are pushed to a new titillating limit. This limit, in which the fantasy of owning one’s body cannot be disarticulated from disowning another, engages in deathly fantasies that not only serve us with insight into our own perversity but also, as Rosen’s top insists, offers building blocks for a new kind of ethics.

I would like to thank Barbara Browning for her thoughtful support and Levi Prombaum for his engagement and care.

- With caution to the reader, this (at 1:50) is an unexceptional, disturbing example that I have in mind: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A00SNNEWQqw

- It is noteworthy that this child Freud writes of is a female, thereby already implicating maybe the oldest power relation of all within his study and research, something that plays a crucial role in his own theorization and my own.

- This gendered configuration — the male figure taking over the female body — can also be interpreted as the Freudian remanence, echoing, in a sense, the already-gendered relation in Freud’s essay between a female subject who fantasizes a male being beaten. Thank you B. Ratskoff for this thoughtful contribution.

- Jasbir Puar’s term “golden handcuffs” describes how the state gives queer subjects rights in order to co-opt them into violent assemblages of power; we should not miss the sadomasochistic valences of this term, implying the pleasures of bondage to the state.