“The crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crows. For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite.

“To be away from home, yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the center of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world—such are a few of the slightest pleasures of those independent, passionate, impartial natures which the tongue can but clumsily define.”

Charles Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life

“The U.S.-Mexican border es una herida abierta where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds. …Gringos in the U.S. Southwest consider the inhabitants of the borderlands transgressors, aliens—whether they possess documents or not, whether they’re Chicanos, Indians or Blacks. Do not enter, trespassers will be raped, maimed, strangled, gassed, shot. The only “legitimate” inhabitants are those in power, the whites and those who align themselves with whites.”

Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera

In 2015, my partner and I fell in love over a particular excerpt from Charles Baudelaire’s The Painter of Modern Life. I’ll admit, late-19th-century French modernist poetry and Baudelaire’s lofty, imperialist fantasies of feeling himself “everywhere at home” was an unlikely point of connection for two queers from different sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. In retrospect, however, I believe the image of the flâneur (the bourgeois, urban explorer) may also hold deep resonance for those of us in diaspora who seek belonging while we’re away from home and embody our willingness to connect across seemingly impenetrable borders—especially when home is not a place to which we can return safely.

Our stubborn will to connect across borders was the glue that drew my partner and me together. We recognized a shared struggle in being away from home, both in the broad, diasporic Jewish sense and in the more regional sense as Californians from different sides of the border: I a Bay Arean from Northern California and she a Tijuanense from Baja California. We were at home together as Californians, but the U.S.-Mexico border fractured that at homeness on multiple fronts, including gender and Jewishness.

The multifaceted, intra-personal divisions we navigate are captured poetically and devastatingly by the late Chicana lesbian poet Gloria Anzaldúa and her canonical text Borderlands/La Frontera. First published in 1967 and quickly adopted as a cornerstone of Third World Feminist thought, Anzaldúa centers the geo-political border between the U.S. and Mexico to explore the inorganic ruptures—both internal and external—that marginalized individuals and collectives reckon with on a daily basis. Anzaldúa’s words are both hyper-specific, speaking from her social location as a queer, Mexican-American woman from the Texan side of the U.S.-Mexico border, yet also broadly relatable, as she narrates the experiences of many who fumble through the complex and contradictory matrix in-and-between privileges and oppressions. I draw on Anzaldúa’s words not because she is a border scholar (and I doubt she would have argued otherwise, despite her posthumous role in the Academy), but because she is a borderlands artist, committed to a form of healing through writing.

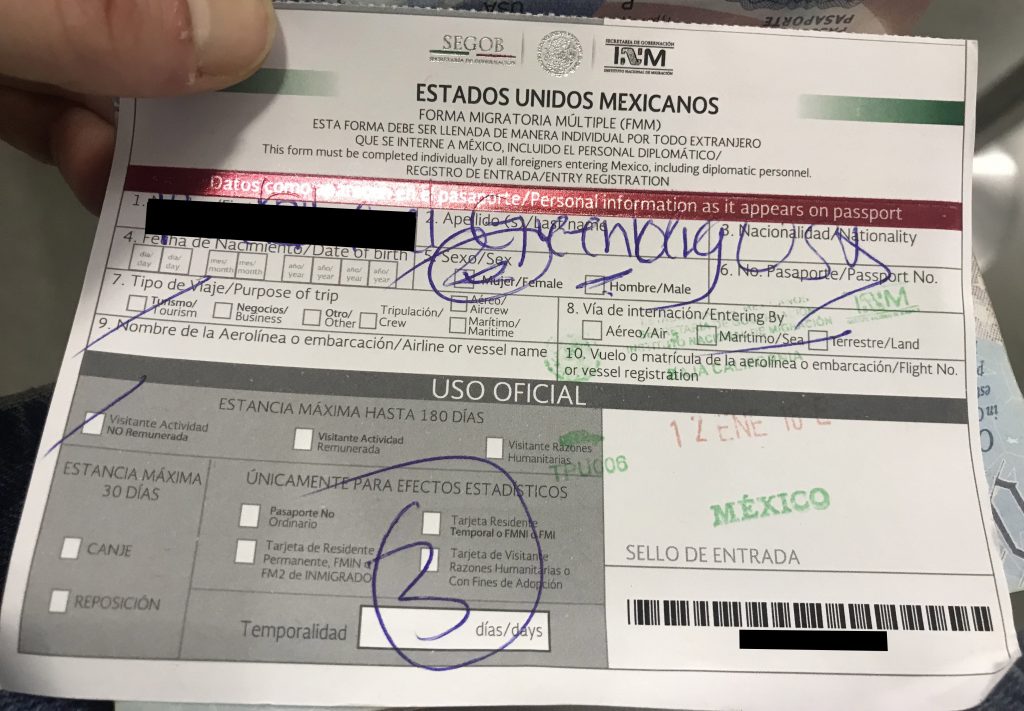

As for me, over the next two years I will write a historical account of 20th-century migration of Jewish communities to the northern Baja California border region, based on research I will conduct at various federal and state archives between Mexico and the United States. Archival work can provoke anxiety for many academics—you carve out weeks, months, sometimes years from your “regular” schedule to dig through old government documents, photos, periodicals, etc., without any guarantee of finding something that supports your scholarly assumptions. But my greatest anxiety as I approach the data collection process does not so much lie in the unknown of archival research but in another realm of ambiguity I know all too well: my legal documents (California ID, Passport, Birth Certificate, Social Security Card) do not match my gender identity, my name, and, increasingly, my physical appearance. Anzaldúa reminds me the importance of naming and reflecting upon how I will be challenged and healed in the process of writing Jewish history across international borders as I exist between the borders of gender. As someone with the racial and legal privileges to experience the border as a site of transit rather than an impenetrable wall, Anzaldúa pushes me to honor my writing time as “a numinous experience…a path/state to something else,” and perhaps an opportunity to envision something beyond the border line’s violent divisiveness.

The U.S.-Mexico border—historically and presently—functions as a State mechanism for the direct and physical exclusion, separation, and imprisonment of the non-white, the economically vulnerable, women, and queer peoples. As a white Jewish American with U.S. citizenship, I am largely shielded from these direct threats that dominate the experiences of so many at the border, not least of which include the past and present horrors of family separation. However, as a transmasculine person whose legal documents match neither my gender expression nor identity, my own queer body’s experience with the border helps to illustrate how institutional border violence functions on both material and ideological levels.

—

Before the United States controlled its modern borders, citizenship and naturalization laws were the primary tools through which our government sought to protect the white, Christian, settler-colonial nation-state in which we live today. Since the codification of nationalization law in 1790, U.S. citizenship has consistently centralized wealth and land rights into the hands of the white, heteronormative, cis-male subject. The Act of 1790 restricted citizenship to “any alien, being a free white person,” and, as Nayan Shah describes, used a lexicon of racial hierarchies to put forth a national expectation of “respectable sexual morals and behavior against images of degeneracy and deviance.” Furthermore, the earliest conceptions of citizenship were bound up with race, class, and gender relations; property and wealth were required to vote, and a racial and patriarchal sexual order maintained and consolidated property within the hands of a white, heteronormative citizenry.

Following the Anglo-American colonization of Mexico’s northern territory (the present-day Southwest, California, Utah, Colorado and southern Wyoming) in 1848, the white supremacist sentiment at the center of U.S. citizenship laws was woven into the fabric of the nation’s new southern border. Our present reality—where economically vulnerable, brown and black humans of all ages (regardless of citizenship status) are routinely marked as illegal, separated from their families and countries of origin, ruthlessly caged, and deprived of due process and judicial oversight—is not a departure from the history of the U.S.-Mexico border, but rather the linear evolution of the white settler-colonial model on which the United States was founded.

Whether through the direct exclusion of all Chinese migrants beginning in 1882, or the ethno-racialized curation and national inclusion of certain (read: white, Western European, Christian) foreign demographics by way of immigration quota policies (1921, 1924, 1952), the United States has routinely used its national borders as militarized buffers that institutionalize and protect a white, European-origin, often Christian, and always heteronormative status quo. By the mid-20th century, previously denigrated European ethnics had been solidified into a dominant whiteness, while Mexican and Latin American-origin peoples continued to be criminalized as an illegal and threatening labor force, independent of their actual legal status. Let us be clear: the U.S.-Mexico border is, and always has been, a spatial manifestation of the U.S. government’s violent war against people of color, poor people, and queer people.

Like citizenship laws, gender has also been a central element of U.S. border politics. Beginning in the 19th century, single, Asian woman migrants at U.S. ports of entry were marked as practitioners of “lewd and immoral” business and behavior by way of the Page Law of 1875. Exclusion from the United States based on non-normative sexual orientation was explicitly written into immigration policy beginning in 1917, wherein “persons with abnormal sexual instincts” were denied entry based on their categorization as, in Eithne Luibhéid’s terms, “constitutional psychopathic inferiors.” Homosexuality was directly banned through immigration legislation in the 1950s and ‘60s, when the category of “sexual deviant” was added to the Immigration and Naturalization Service’s list of legally excludable migrant subjects. Luibhéid notes that it was not until 1990 that a congressional report explicitly made “clear that the U.S. does not view personal decisions about sexual orientation as a danger to other people in our society [and repeals] the ‘sexual deviation’ exclusion ground [in immigration law].” While homophobic immigration legislation focused on maintaining a heterosexual status quo in the U.S., race, class, gender, and the performance of gender (along a strict binary) always remained central to the way the State surveilled, identified, and criminalized non-normative sexualities.

—

Academics talk frequently about being producers and practitioners of knowledge. Knowledge is power, we often remind ourselves. Less often, we admit to ourselves that power doesn’t always make us feel powerful. I have chosen a research project that will put me into contact with the U.S.-Mexico border on a near daily basis, and despite my growing knowledge of the region, I struggle to feel powerful. Instead, I feel powerfully aware of how vulnerable my body becomes when occupying a space that is marked by a long and violent history of systemic monitoring, policing, and punishing of those deemed threatening to national security, most often non-white and/or queer people.

As a queer scholar who doesn’t do “queer work,” I have struggled with how to augment traditional research methodologies in order to accommodate my trans body. Despite being an extrovert with above average social skills for an academic, it was not easy when I decided to pursue a historical project that would keep me isolated in government archives. My original dissertation proposal was a contemporary study of identity amongst Latinx Jews, and in the fall of 2016 I began collecting phone interviews with first-generation Mexican Jews who had migrated to Southern California in the 1970s–‘80s. In early 2017, when I began living openly as a transmasculine person, the thought of continuing a research project that involved live human subjects terrified me.

I would create fantasies in my head in which I would re-introduce myself to former interviewees as Max Greenberg, the twin brother of the woman-identified UCLA doctoral student with whom they had spoken six months earlier. Yes, my sister and I are both doing doctoral research on Latinx Jews; no, there is no conflict of interest; and yes, she shared your contact information with me, but no, I can’t tell you where she is/what she’s doing with her studies/why she never followed up for a second interview… Sometimes escapist fantasies, no matter how absurd, are the most honest form of self-care that we can give ourselves during times of monumental change.

Since beginning my medical transition in 2017, the illusion of safety and space for queerness that I projected upon “The Archive” has slowly unraveled. This is largely because my body is aligning more and more with my sense-of-self, but my legal documents are not. This presents a significant challenge when planning trips to government archives that require multiple forms of legal identification and letters of recommendation by accredited academic institutions. I have begun the slow and costly process of updating my name and gender markers in the state of California, but it will be years before I will complete the necessary changes to my federal identification documents, including my passport and social security card. My doctoral research funding will not wait for the government to catch up with my identity—and neither will I.

And yet, I am afraid. I am afraid of how my trans body will be categorized in the context of these institutional spaces in which I’m eager to establish myself as a “distinguished” and “promising” graduate student; I am afraid (perhaps naively, perhaps not) that my queerness will outweigh my privileges as a white, U.S. citizen, and compromise my cross-border mobility. I am ashamed that the threat of exposure and rejection that I now fear from the State was so carelessly misdirected onto so many research subjects I never met. Above all, I am ashamed that despite all my knowledge about the history and present reality of surveillance, exclusion, and brutality along our nation’s borders, I nonetheless leaned into my whiteness and its privileges of normativity and mobility, thinking it would shield the State from seeing and challenging the legitimacy of my queer body within its borders. I am interested in naming and documenting my own misguided and, at times, delusional thought process not because I think dissertating while transitioning is inherently untimely, or schizophrenic (though sometimes it feels as such). Rather, I believe that my citizenship privilege coupled with my queer lens allows me to recognize international borders as ideological and temporal constructions that nevertheless inflict material violence.

—

The ways in which the U.S.-Mexico border has excluded, fractured, and criminalized bodies based on race, class, gender, sexuality, and legal status has been well-documented by scholars on the vanguard of Border Studies. Less visible, however, are the ways in which the U.S.-Mexico border has transformed Jewish subjectivity from an inherently diverse, dynamic, diasporic, ethno-religious identity into a rigid white, capitalistic, nativist arm of American exceptionalism. We are quick to see how the dynamics of American settler-colonialism and white supremacy have emboldened a form of Jewish supremacy in the context of Israel-Palestine. But how are we to understand such forms of Jewish nationalism and supremacy in the context of the U.S.-Mexico borderlands? The urgency of this question has been at the center of many difficult discussions between my partner and me over the years. I would pepper her with trivial inquiries, pushing her to quantify her religious practices in terms that mirrored my own American Ashkenazi understanding of Judaism.

My difficulty in understanding my partner’s Jewishness and more broadly what it means to be Jewish outside the United States is, in part, a symptom of the way Jewish day schools in the United States teach Jewish history; I am a recovering alumnus of one such institution. I am not alone in feeling that American Jewish education has failed generations of youth by retrofitting Jewish history into a linear narrative that began with the Bible, pivoted at the point of Ashkenazi emigration from Europe, and ended around the mid-20th-century emergence of the United States and Israel as dual Jewish nation-states/homelands. Much of my research in graduate school has been motivated by my own deep frustration towards this historical model. How many of our Jewish siblings and allies are rendered invisible by way of this abridged narrative? What are the costs of augmenting our histories to fit into the selective prism of American exceptionalism, the longstanding myth of America’s national uniqueness. We are living the consequences now, as younger generations of American Jews become increasingly vocal about their disapproval of American Jewish institutions, leaders, and benefactors, and reject Israel’s institutionalization of racism, discrimination, and apartheid, its escalating colonization of Palestinian territories, and the continued massacre of Palestinian peoples.

Alongside American Jewish education, the U.S.-Mexico border has also retrofitted the American Jewish psyche to fit within the paradigm of American exceptionalism and its accompanying racist, nativist, and anti-diasporic sentiments. Historian Tony Michels has critically interrogated the Jewish version of American exceptionalism, which purports that the United States has served as a unique home base for Jews (2010). Distinct from the European context, Jewish immigrants to the U.S. and their descendants were never forced to undergo a process of emancipation as a necessary step towards proving themselves worthy of citizenship and social integration. Michels pushes us to revisit the exceptionalist model in part because it ignores the similarities between American and European Jewries. Beyond the European context, however, I believe exceptionalism discourages comparisons between the American Jewish experience and all Jewish experiences across the diaspora, particularly in the global south.

American Jewish exceptionalism mimics and perpetuates the violent logic of the U.S.-Mexico border for a few reasons. Primarily, it upholds the racist, elitist fantasy that with the exception of Israel, all Jews live in, or aspire to live in, the United States; secondly, it perpetuates the belief that Jewishness in a United States context reflects the way Jewishness looks and feels in all contexts; and lastly—and most specific to the context of the Americas—American Jewish exceptionalism leans into the State logic of the United States border as a tool that whitens and enriches those who live within such a border and racializes and criminalizes those with limited/no legally sanctioned mobility across the border. The U.S.-Mexico border thus functions as an ideological container for American whiteness and wealth, and a necessary and exclusionary boundary from so-called Latin American brownness, blackness, criminality, and poverty.

Our country’s geo-political borders—as physical extensions of American exceptionalism and notions of citizenship and belonging—push us to understand Jewishness as authentic only within the context of white supremacy and Western nationalism. When we understand how American exceptionalism and borders shape our understanding of Jewishness in the United States, we can unpack and disempower the racism, nationalism, and elitism that underpins the declaration I didn’t know there were Jews in Latin America, an utterance directed at me on numerous occasions by wealthy, well-educated, white American Jews. Our fears of leaning into diaspora and holding space for the infinite options that diasporism affords us—as Jews, as intersectional beings—is a direct consequence of American exceptionalism and the geo-political borders that reinforce it.

—

Anzaldúa says that writing is “an endless cycle of making it worse, making it better, but always making meaning out of the experience, whatever it may be.” As I wrote, I made it worse when I recognized the wounds I carry after years of being wedged into awkwardly fitting categories of identity used by the State as a measurement of inclusion. As I wrote, I made it better when I realized I was born with all the tools necessary to liberate myself from ill-fitting boxes and dangerous dichotomies and hold space for the contradictory matrix of privileges and oppressions I contain within me. As I wrote, I made meaning out the experience by reading Baudelaire, the Western European modernist and cultural imperialist, alongside Anzaldúa, the queer mestiza fronteriza, an unlikely literary duet pointed me towards a new flâneur, a queerer flâneur, advising me to find a diasporic consciousness and see myself “everywhere at home,” not so much in the physical sense, but in the interpersonal human sense, between and among a multitude of Jews and our allies.