I.

In the Auschwitz concentration camp, long before she was a mother and not long after she’d dreamt of becoming one, Grandma Eva almost stopped menstruating. It was a soup they gave her, she told me, some secret ingredient meant to mottle her Jewish womb. For her story, there’d be no future home to tell it, nor for it to hide inside.

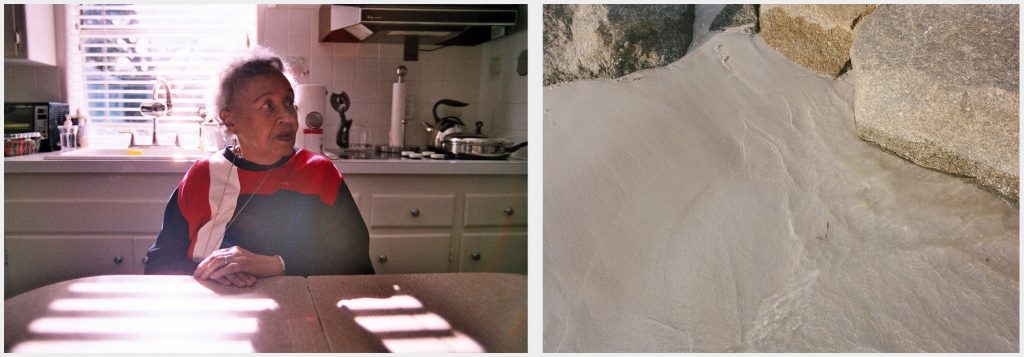

But the blood came anyway. She hadn’t the luxury, then, of finding small hope in her body’s ability to still function, mammalian and alive. Everything, she’d explain later, was purposeful. Hands between her legs, the warmth a tiny cavern in which to tuck herself away, warm and brief; she put the blood on her cheeks, rubbed it in like a rouge till the pink filled the gaunt space. If she was healthy, she could work; if she could work, she’d live. Only the well-rested are blessed with the countenance of lucidity. Now she looked like one of the living.

She went to the field to sow and to pick and carry bricks. The S.S. on his bike, spiteful or clumsy or both, rammed the front of his wheel toward then on and over her; she was, perhaps, the kind of untouchable he watched at a distance—her safety afforded by his disgust, a heavy and salient border. When he dared to breach it, she fell to the ground, cracked but still whole. When the camps were liberated, she stayed in a hospital bed for one year, in a brace made of steel, like a cage. She drank wine and ate apples to fortify her bones, the red of the fruit like the one that still moved inside her. One day, my father, unexpectedly, would live there, a baby growing with her pain; one day, I would feel it, too, all that she’d swallowed.

II.

My mother’s mother, Elba, my Nana, told me stories from the island of her birth, magical-realist dramas she relayed like truths: the soil cracked open and swallowed a woman whole, a baby girl met the soul of her aunt as she crossed over, men of her own skin tone would only hurt you.

I believed and then didn’t believe them all, though later other tales became new facts, too: she wasn’t black or brown, she wasn’t Puerto Rican, she didn’t hide her Catholicism in a drawer with her socks. She’d married a white Jewish man, enfolded herself into his verisimilitudes—he was realer than her, she felt. Her mother language roiled on her tongue until she swallowed it, replaced it with new words, new tastes, new parameters with which to align her whole self. “I’m American,” she’d say, though it wasn’t a lie, to the exclusion of all else. Her truth leaked like water when she needed it—when my mother feared a spiritual attack, Nana placed oranges on her windowsills, lit candles, performed some type of brujería. She didn’t seem to age, only live and then one day die.

The only signifier of her own time was the swelling in her legs. She never complained, but lay in bed, moored to her sheets, limbs like molasses. She was heavy but mostly on the inside; secrets weighed more than her knees did. Even this reality never fully made its way to my ears—she’d limp, but just a little; sigh, but just quietly.

III.

I was once so afraid of my own body that I tried to muffle it. With the loss of my childhood had gone the symmetry of my face and the ignorance of my history; I knew now women could feel ugly because I did, that your heritage could be comprised of secrets because mine was. (They don’t tell you puberty garners you not just body hair but the sudden, striking awareness of yourself.) I prayed to stay ten forever, slouched over my growing breasts as if they were flowers and puberty—that encroaching womanhood that carried with it both the power and hurt my matriarchs held, too—was a sunlight I could block with my own shadow. I accordioned myself till the cavity of my chest got smaller and my spine curved like an S. I lay in bed, stuck to my sheets; with nothing to fortify my own bones, the pain would return again and again. My legs hurt for reasons not completely clear to me. Still today, getting out of bed is no burden, though it takes an awfully long time.

It took nearly two decades for me to see the way I’d destroyed my body’s terrain like it was earth: my vertebrae glowing in X-ray, its curvature wholly (retroactively) preventable. Two at the base of my spine had rotated completely, right at my root; I imagined a line reverberating from them, stretching to the earth beneath, twisted and unsure of its reach. They were, I pictured, coming to face each other, two small pieces of my history separating the top of me from the bottom. It is the place where the contours of my histories merge—where they turn me, at once, forward and backward and sideways, to my past and to my own self, little matriarchies shaping my alignment.

This, too, is a story I forged like a folktale, a series of truths fortifying me like fruit. “Your pain is your joy in another form,” said a book my mother read to me.