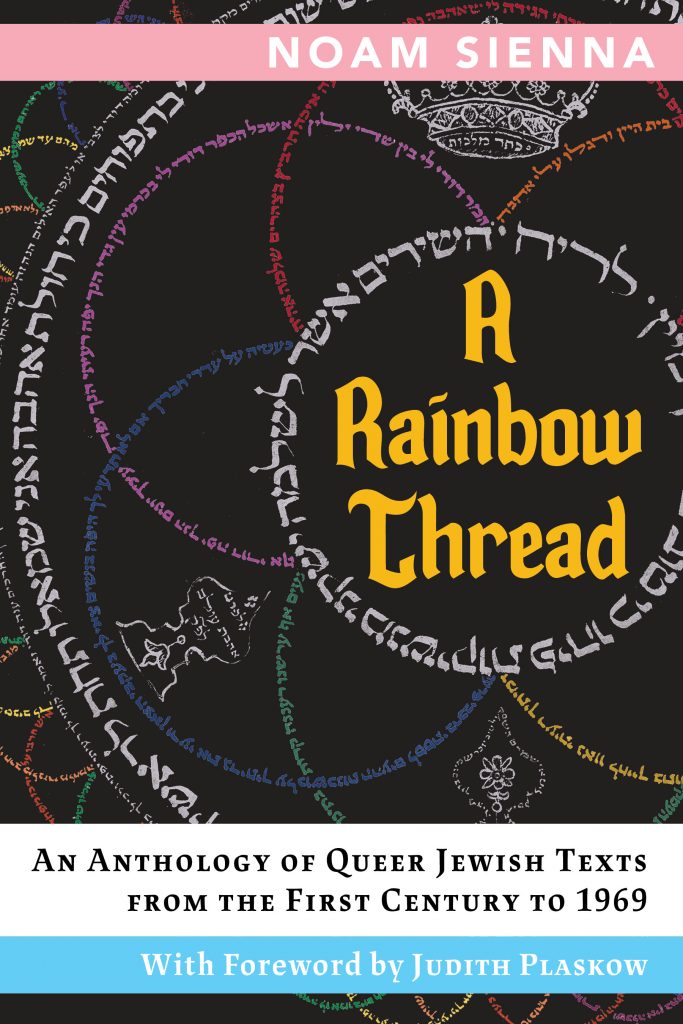

The title of my forthcoming anthology, A Rainbow Thread: Queer Jewish Texts from the First Century to 1969 (Philadelphia: Print-O-Craft Press, 2019), speaks to the central balancing act that the book attempts to undertake. On the one hand, queer or LGBTQ Jewish history is an infinite rainbow, with no beginning or end, and with no clear boundaries between its different facets. On the other hand, there is a thread: a continuity that links our lives, our joys, and our struggles today to an ancestral heritage in the past and to our inheritors in the future. In this book, I work from the perspective that history is not an uninterrupted march towards some universal goal, but a messy, contingent, and complex network of processes, connections, interruptions, and innovations. Certainly, it is irresponsible to project our identities onto people in the past; at the same time, however, it is also irresponsible to ignore the shared practices, behaviors, and experiences that link these stories to other places and times, and that offer clear resonances with our lives today.

The title of my forthcoming anthology, A Rainbow Thread: Queer Jewish Texts from the First Century to 1969 (Philadelphia: Print-O-Craft Press, 2019), speaks to the central balancing act that the book attempts to undertake. On the one hand, queer or LGBTQ Jewish history is an infinite rainbow, with no beginning or end, and with no clear boundaries between its different facets. On the other hand, there is a thread: a continuity that links our lives, our joys, and our struggles today to an ancestral heritage in the past and to our inheritors in the future. In this book, I work from the perspective that history is not an uninterrupted march towards some universal goal, but a messy, contingent, and complex network of processes, connections, interruptions, and innovations. Certainly, it is irresponsible to project our identities onto people in the past; at the same time, however, it is also irresponsible to ignore the shared practices, behaviors, and experiences that link these stories to other places and times, and that offer clear resonances with our lives today.

The excerpts presented here offer some tastes of how we might encounter primary historical documents as a field of possibility for imagining new futures. This approach to history is one that has been articulated by both queer scholars (such as Caroline Dinshaw and José Esteban Muñoz) and Jewish ones (most famously, Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi). The first two texts offer classical midrashim—one on the character of Dinah, and another on the proper bond between study partners (havruta). Rereading them through queer eyes, however, demonstrates how the imagination of our tradition can continue broadening our vision of Jewishness today. The assertion that “it is not difficult for the Holy Blessed One” to transform a person’s sex like a potter transforms clay on the wheel affirms our contemporary understanding of the malleability of sex and gender, while the suggestion that a man’s primary emotional and even physical intimacy should be with his male study partner makes space for a Jewish framework of same-sex relationships. The second and third sources are rare windows into the actual sexual and gendered lives of ordinary Jews. While the prescriptions of rabbinic authorities might attempt to deny the existence of such lives, it is clear from these texts that Jewish sexuality and gender in practice was not as restricted as we might think, not by boundaries of gender, sex, nationality, or religion. The final two sources testify to some of the political and social transformations in the 20th century, showing how new ideas about sexual identity were articulated in various Jewish contexts.

These excerpts—and the book as a whole—are not an attempt to show that Judaism “really” promotes queer inclusion, nor are they merely an anachronistic attempt to say “Look! There were [insert-identity-here] Jews in the past!” Instead, this project is intended to do something both deeper and more expansively imaginative: to push the reader to rethink what queer Judaism could be, and to encourage them to question what they have assumed about how Jews have understood sexuality and gender over our long history as a people. Queer Jewish identity is so often imagined as existing in spite of—or in opposition to—the world of Jewish tradition. These texts invite us into the process of constantly rereading, reimagining, and revising our understanding of what Judaism has meant, and what it can mean for us today.

—

14. Dinah’s Sex is Changed: A Midrash (Land of Israel, Sixth to Eighth Centuries CE)

This remarkable teaching, from a midrashic collection known as Tanḥuma-Yelammedenu, comments on the biblical account of the birth of Ya‘aqov and Leah’s daughter, Dinah. The rabbis explain that Dinah was originally male, but transformed at Leah’s request into a girl (a tradition that is recorded elsewhere in rabbinic literature: see Bereshit Rabbah 72:6 and JT Berakhot 9:3). Drawing on a passage in Jeremiah where God is compared to a potter who can make and remake vessels at will, so too human sex is portrayed as equally malleable. “It is not difficult for the Holy Blessed One,” one rabbi says, “to convert females into males and males into females,” even at the moment of birth. The Tanḥuma-Yelammedenu is one of three early midrashic collections attributed to the fourth-century rabbi Tanḥuma bar Abba; it is called Yelammedenu because many of its sections begin with yelammedenu rabbenu, “Let our master teach us.” It was probably compiled and edited in the Land of Israel between the fifth and eighth centuries.

“And God remembered Raḥel” [Gen. 30:22]. Let our master teach us: if a man’s wife is pregnant, may he pray, “may it be Your will that my wife give birth to a son”? Thus our masters teach us: the man whose wife is pregnant and who prays “may it be Your will that my wife give birth to a son”—this is a prayer in vain. R. Huna, however, said in the name of R. Yose: “Even though we have been taught that the husband of a pregnant woman who prays ‘May it be Your will that my wife give birth to a son’ is saying a prayer in vain, this is not the case; but rather even as she commences labor, he may pray for a son. For it is not difficult for the Holy Blessed One to convert females into males and males into females.” And thus it is explained by Yirmiyahu: “I went down to the potter’s house, and there he was, working at the wheels. And when the vessel he was making of clay was spoiled in the hand of the potter, he made another vessel, as it seemed good to the potter to make it [Jer. 18:3-4].” And then did not the Holy Blessed One say to Yirmiyahu: “Cannot I do with you as this potter, O house of Israel? declares the LORD (Jer. 18:6)”?

And thus you find this with Leah: after she had given birth to six sons, she saw in a prophecy that twelve tribes would be established from Ya‘aqov [and his sons]. She had already given birth to six sons, and was pregnant with her seventh, and the two handmaidens had each had two sons, making ten sons in all; so Leah arose and pleaded with the Holy Blessed One, saying: “Master of the Universe, twelve tribes are to come from Ya‘aqov, and since I have already given birth to six sons, and am pregnant with a seventh, and each of the handmaidens has had two sons, this is already ten. If this child [within me] is a male, my sister Raḥel will not have as many [sons] as one of the handmaidens.” Immediately the Holy Blessed One heard her prayer and converted the fetus in her womb into a female, as it is said: “And afterwards [aḥar] she bore a daughter and called her Dinah” [Gen. 30:21]—it is not written aḥeret [in the feminine form] but aḥar [in the masculine]. And why did Leah call her Dinah? Because the righteous Leah had stood for justice [din] before the Holy Blessed One, who said to her: “You are merciful, and so I too shall be merciful to her.” Immediately, “God remembered Raḥel” [Gen. 30:22].

15. A Midrash on the Bond Between Study Companions (Babylonia, Seventh to Ninth Centuries CE)

This teaching expands on the statement in Pirqei Avot 1:6, that one should “appoint for yourself a teacher, and acquire for yourself a companion.” Describing the character of an ideal companion [ḥaver], the midrash explains that one should eat, drink, study, and sleep with one’s companion, and reveal to them all secrets. In other words, the ḥaver is portrayed here as a man’s most emotionally and socially intimate partner; while one’s wife is necessary for rearing a family, it is the same-sex bond between study partners [ḥavruta] which was, for the rabbis, their most significant relationship. Indeed, several ancient and modern sources confirm that this was true in many actual cases (see sources 13, 48, 52, and 77). The Avot deRabbi Natan is a midrashic collection that expands on the teachings in Pirqei Avot, one of the tractates of the Mishna; while the text preserves some older material, the Avot most likely took its final form during the geonic period, between the seventh and ninth centuries CE.

“And acquire for yourself a companion [ḥaver]” [Mishnah Avot 1:6]. How [is this to be done]? This teaches that a man should acquire for himself a companion, and that he should eat with him, drink with him, read with him, study with him, sleep with him, and reveal to him all his secrets: the secrets of Torah and the secrets of worldly matters [derekh erets]. For when they sit and occupy themselves with Torah, and one of them makes an error in a matter of legal reasoning or in recalling a citation, or if he declares a impure thing to be pure or a pure thing impure, or a forbidden thing permitted and a permitted thing forbidden—then his companion will return him [to the correct reasoning]. And from where [in Scripture can we learn] that when his companion guides him and studies with him, that they receive a good reward for their labor? As it is said: “Two are better than one, for they have a good reward for their labor [Eccl. 4:9].”

37. Moshko’s Sexual Escapades are Revealed in Court (Arta, 1561)

This fascinating responsum records at great length the sexual escapades of a certain Jew named Moshko (i.e. ‘little Moses’) Kohen, from the city of Arta in northwestern Greece (then part of the Ottoman Empire). The accounts of sexual behavior in this responsum are completely unparalleled for their extensiveness and specificity. And perhaps even more astonishing, they are brought in only as a side-note to the main question, which concerns the validity of a betrothal with conflicting accounts of what was offered, what the young man said, and what the young woman replied. As a way of undermining the case, a number of citizens inform the judges of the disqualifying character of the witnesses to the betrothal. The first, Yehuda Kohen, is shown to be a serial gambler, and thus ineligible for testimony in a Jewish court, as per BT Sanhedrin 24b. Moshko, on the other hand, is well-known in the local community for his sexual activity with men, and numerous witnesses come forward to attest to his liaisons with Jewish and non-Jewish men. His testimony is disqualified, and in the end both the witnesses and the original ‘groom’ confess to having fabricated the whole affair; the marriage is declared null and void, and there is no reference to any repercussions or follow-up investigation of Moshko’s behavior, which was clearly openly known already. The adjudicating rabbi, Shmu’el ben Moshe de Medina (or MaHaRaShDaM, 1505-1589), was born and raised in Salonica, and was one of the chief rabbinic authorities for the Sephardi community there.

We, the undersigned, convened as the three judges of a single Beit Din [Jewish court], when Yeshua‘, son of the honored rabbi Avraham, came before us and told us: “You should know, my masters, that seventeen days ago (which was a Friday), I left my house at dusk and found these two bachelors [baḥurim], namely: Yehuda, son of Yitsḥaq Kohen, and Moshko Kohen. I said to them, ‘Come with me!’ and we all left our building and entered the courtyard of this building. I called for the young woman, Flori, daughter of the rabbi Yosef. When she came down to us, I took out one new Venetian zecchino; I said to her, ‘Take this as your marriage payment,’ and [I said] to them [i.e. Yehuda and Moshko], ‘You will be my witnesses.’ She reached out her hand and took it.” Afterwards, the aforementioned Moshko came before us and testified as a witness [to these events]… [However, the judges suspected that this engagement was fraudulent and began interrogating the witnesses’ stories. Finally, the reliability of the witnesses themselves is called into question.]

At a later session [of the court], Leon, son of the honorable rabbi Simo, came before us and testified that he saw the aforementioned Yehuda Kohen gambling, at a time when there was a ḥerem [ban] in the community on gambling anytime other than a holiday, or on the Fast of Esther and Purim; but he was gambling nonetheless [and thus disqualified]! This Yehuda claimed that because he came here to Arta from another country, he did not accept the ḥerem, but we know that it has already been two years since he has lived here with his father and mother and brother, and he has no intention of returning to the place where he came from. And Ya‘aqov, son of the honorable rabbi Moshe Barzilai, testified to the same effect, that the aforementioned Yehuda was gambling as described above, and [the report] was sustained.

At this session, Rabbi Yosef Marato came before us and told us: “You should know, my masters, that I have witnesses [who can testify] against Moshko, for he is disqualified from testimony because of the transgressions he has committed. Now, call these witnesses, and bring [Moshko] to the Beit Din, and they will testify against him.” We, the court, called for [Moshko] several times and he did not want to come. We then sent an agent of the court, who warned him, in front of witnesses, but he still did not want to come. The witnesses then came and testified before us regarding this warning, and they were: Rabbi David bar Mordekhai, and Rabbi Moshe Tsoref, and Rabbi Yosef and Yisrael Berakha. Since we saw that [Moshko] did not want to come, we accepted the testimony of the witnesses [against him].

First, Rabbi Ḥayyim Gabi came and testified that he saw the aforementioned Moshko on Yom Kippur, and he was wasting seed [mashḥit zera‘o levaṭala, i.e. masturbating]. Then, David bar Nissim came and testified how this past summer, he was travelling through a village with a certain Turk, and they crossed through an orchard to ask the owner to sell them some fruit; there they saw this Moshko with a certain bachelor [baḥur], and he was being sexually penetrated by him [nirva‘ ‘imo bemishkav zakhur]. When they saw [Gabi and the Turk], they fled and separated from each other, and ran away with their pants undone.

Then, Ḥayyim bar Matitya came and testified how once he was travelling by the place with the large, smooth boulder, and there he saw the aforementioned Moshko, and a certain Turk was penetrating him by his consent [rovea‘ oto lirtsono]—this deed was around two months ago. Then, the bachelor Avraham di Mili came and testified that [Moshko] pursued him to force him into penetrative sex [la’anoso bemishkav zakhur], but he did not want to. Then, the bachelor Eli‘ezer bar Avraham came and testified how he heard so many rumours about Moshko when he was in Ioannina, namely that he was having sex [nirva‘] with this Turk, that it gave him a bad reputation and they would call him a disgraceful epithet. [This report] was sustained. At this session, Rabbi Yuda Tsuri came before us and testified: “Around two years ago, I went with some other bachelors to Moshko’s house, and we ate and drank. After the meal, all the bachelors began to head to their homes, and I myself saw the aforementioned Moshko being penetrated [nirva‘] by Ya‘aqov Mazal-Tov.” [This report] was sustained.

And at a later session, Avraham bar Mar David came and said: “About a year and a half ago, I was in the house of the aforementioned Moshko, and I saw him penetrating [rovea‘] a certain bachelor.” All these testimonies were given under the threat of a ḥerem [ban] that we instituted, in order to ascertain the truth, and they were sustained… At a later session when we convened as a court, the bachelor Yeshua‘, the son of Avraham, came before us and confessed the transgression that he had committed, regarding what he had claimed before the court: namely, that he had been betrothed to the young woman Flori, daughter of the honorable rabbi Yosef. For it had all been lies and falsehoods, and he had never been betrothed to this young woman. In our presence he admitted how he had sinned a terrible sin in spreading this rumour, and told us what things had brought him to do this. He asked forgiveness from Rabbi Yosef, the father of the young woman, falling to the ground and kissing his feet so that he would forgive him and so that God could absolve him of his transgression.

At this session, the bachelors Moshko and Yehuda Kohen, who had testified to this marriage, came before us and confessed their transgression, that they had transgressed and sinned in what they had testified regarding this marriage, since it was all lies and falsehoods. They told us the circumstances that had led them to do this, and asked forgiveness from God to absolve their transgressions, and this was sustained.

73. A Jewish Immigrant’s Gender Transition is Revealed After Death (Chicago, 1915)

Like other cases of people who were raised as women but who lived as men (see source 51), it is difficult to know exactly how to interpret the story of Ben Rosenstein; based on the surviving records, it seems most appropriate to use his chosen name and pronouns. Born Ida Weinstein in Poland in 1889, he came to the United States in 1908 and landed in New York, where he joined the thousands of other young Jewish immigrants working low-paying factory jobs. After meeting his partner Pauline Rosenstein, he transitioned to living as a man, apparently inspired in part by the socialist atmosphere of the Jewish labor movement (this article describes him reading Marx and Tolstoy; another article claims that he attended Yiddish socialist lectures on the Lower East Side). The couple moved to Cleveland, then Detroit, where they are recorded in the 1910 census as the newly-married couple “Bennie [sic] and Pauline Rosenstein.” Shortly afterwards, Ben Rosenstein contracted tuberculosis and they moved to Chicago, where despite support from HIAS (the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) he died in 1915. The sensationalist Tribune reporter claims that Rosenstein was a “girl husband” whose “industrial marriage” was simply one of economic convenience; but his own testimony—such as his refusal of a women’s sanitarium, and his wish to be buried in his suit—suggests that he was sincere and serious about his masculine identity (and his commitment to Pauline). At the same time, some aspects of Ben’s identity are paralleled by the presence of masculine women in lesbian communities of the early 20th century, and Ben and Pauline’s relationship might also be understood as an early forerunner of the ‘butch/femme’ culture of working-class lesbians that was common in industrial American cities like Chicago, New York, and Buffalo, in the 1920s-1950s and beyond.

DEATH REVEALS GIRL ‘WED’ GIRL TO FIGHT WANT

“Husband” Got Man’s Wage with Mallet After “Industrial Union.”

THEN PHTHISIS CAME.

Three persons yesterday morning crowded the small bedroom in the rear of the second floor of 2146 Ogden Avenue. They were Mr. and Mrs. Ben Rosenstein and Mrs. Rosenstein’s mother. Ben Rosenstein was dying—of tuberculosis at the age of 26.

“Pauline, I am sorry,”—the effort brought coughs. “Please bury me in my first black suit—you know.” The young wife at the bedside buried her face in a pillow. The mother at the end of the bed prayed aloud in Hebrew. The dying victim continued between short labored breaths: “We’ve been happy. I think I have done right. I wish it was true that ‘dead men tell no tales.’”

Doctor Reveals Grim Joke.

A few hours later Ben Rosenstein died. The undertaker and the doctor revealed the grimness of the dying joke. Ben Rosenstein was a woman.

Seven years ago Ida Weinstein landed at Ellis Island, a flaxen haired, full cheeked Jewish immigrant from Russian Poland. She brought with her to Pittsburgh the two children of her brother-in-law, Sam Cohen. Sam had paid her passage.

Ida Weinstein at 19 years old found that the wage for a girl supply worker in a cigar factory was not one that she could live on. In domestic service she was handicapped by her inexperience and the position did not coincide with her ideas of American liberty.

Read Marx and Tolstoi

She had been reading Marx and Tolstoi. At the Jewish Shelter house in New York she met Pauline Rosenstein, 19 years old, very frail, and out of work. The girls roomed together to cut expense. In their hall bedroom one night they worked out the new idea. Ida, the strong one, could earn a better wage as a man than the two could as women. Ergo, Ida should be a man. They would get married. An “industrial wedding,” they called it. So they went to Cleveland and took a room as Mr. and Mrs. Ben Cohen.

The girl husband had clipped her hair and dressed herself in a black suit of clothes. She found factory work and was able to obtain a salary much higher than she had received as a woman. The work was harder—but then, Ida told Pauline she was strong and by extra exertion could work right along with the men in the factory or the workshop. Bigger Pay Envelope.

The extra exertion was forgotten in the joy of the bigger pay envelope. The girls were able to live in better quarters, eat better food, and go to the theater once a week. Pauline worked at such odd jobs as she could get. “Ben Rosenstein and his wife” never owed the room rent and their credit was always good at the delicatessen. They always went out together in the morning. The girl husband donned overalls and swung a mallet in a furniture factory. She was in the packing department. Aside from a high pitched voice, which the other workmen joked about. “Ben Rosenstein” was considered a good employé and a willing worker.

In the course of time they moved to Detroit. Again in the packing department of a furniture factory Ida found wages more satisfactory than those received by the women workers. She was even able at times to leave Pauline at home and adventure into the smoke hazy poolrooms or behind the mystic screens of saloons.

Begins to Lose Weight.

Then the industrial husband began to lose weight. She returned home at night exhausted, and arose in the morning tired. She noticed that the fringe of cropped blonde hair was frequently damp on her forehead. She began to lag at her work. One night she came home with her arms aching and pains running through her back. Her face was damp with perspiration and her hand were cold.

The next morning the boss put another workman in the place of the absent “Ben Rosenstein.” The industrial husband had broken down under the burden of a man’s work. She lost weight—a severe cold—and she found herself too weak to even search for a new job, much less fill it. Unable to make out on the “woman” salary of Pauline, who was working in a hospital, the two young women invested the remainder or their money in a railroad ticket and came to Chicago. For three or four years the name of “Ben Rosenstein” has been carried on the books of the Jewish Aid society. The charity investigators reported that “Ben Rosenstein had tuberculosis, that he was too weak to do any work, that he was in need of medical attention.”

Physicians from the society examined the patient, according to Pauline Rosenstein, and discovered the secret of her hidden sex. They offered to place her in a sanitarium in the country where she might recover. But they insisted she would have to put in the woman’s ward. The young woman would not consent.

In the meantime Pauline’s mother, who did not know until yesterday that her daughter’s “husband” was not a man, was trying to get Pauline to separate from her husband. “He is a sick man, my daughter,” she said. “He can’t live long. You must get a ‘get’”. A “get” is a ritualistic divorce under the orthodox Hebrew church which a childless wife must receive from her dying husband if she wishes to marry again without the consent of her husband’s brothers.

Ida Weinstein’s first dress in six years will be a shroud. She will be buried tomorrow. Sam Cohen went out in the backyard last night and burned “Ben Rosenstein’s first black suit.”

Pauline Tells of Match

Pauline Rosenstein, 26 years old, sat on a stool next to the stove in the kitchen of her home and told her side of the “economic marriage.” Sometimes she referred to her dead companion as “him” and sometimes as “her.” “I have been working awful hard while she has been sick,” she said, “sometimes eighteen hours a day, just to keep things going along with the money from the society.”

“Many times I wished that I had dressed up like a man like Ida. I would have been willing to do it during this last sickness, but I was afraid. Ida was not afraid. I feel I have lost my best friend in the world.”

DRESS, NOT SUIT, WILL BE SHROUD

Girl “Husband” to Be Buried Today in Woman’s Garments

Ida Weinstein will wear today the first dress she has worn in seven years. It will be a burial dress. When the rabbi reads the Hebrew burial service he will say nothing about “Ben Rosenstein”—the name Ida Weinstein assumed to help support her girl “wife,” Pauline Rosenstein. The black suit which Ida Weinstein wore when she started the “industrial union” with Pauline Rosenstein will not be the funeral garb of the “girl husband,” as she requested while dying in the Ogden avenue flat. An order from the physician caused the suit to be burned.

In the flat where “little Bennie,” as the girl furniture worker was known among her friends on the west side, lived Pauline cried and cried yesterday. She sat during most of the day at the head of a black bundle which lay on the floor. Two candles burned at one end of it. Terrible Fight for Food.

“I wish I could bring her back,” she said. “What does it matter now, though. She’s dead. If I could only tell how much she was to me. I wish I could tell the terrible fights for food that we have made together. Seven years ago ‘little Bennie’ and I started out to make our way. It was for me that she died.” Pauline Rosenstein’s mother was in the room. It was cold. Occasionally the mother turned over the few coals in the stove with an iron poker. The stove gave little heat.

“Won’t you eat something—just a bite?” the mother asked. “I don’t want to be bothered,” came back the answer from the girl. “I can’t eat. I only want to think of ‘little Bennie.’” Relatives of the girl will look after the burial, which will take place this morning.

Physician Tells of Case

Dr. Isadore M. Trace of 924 South Ashland avenue, connected with the Jewish Aid Society, said the case was one of the strangest he ever encountered or heard of. Dr Trace was one of the physicians who examined “Ben Rosenstein” when the “girl husband” was seized with tuberculosis and discovered his patient’s real sex, although he did not expose the stricken young woman.

“The fact that the girl masqueraded as a man in order that she earn a man’s wage to enable herself and Pauline to live,” said Dr. Trace, “offers much for economists and social workers to think about. All other considerations set aside, it certainly showed heroic courage.”

77. Mordechai Jiří Langer Writes History of Homosexuality in Judaism (Prague, 1923)

Mordechai Jiří Langer (1894-1943) was a Czech Jewish writer and poet, described by Shaun Halper as “the first intellectual in Jewish history to seriously engage with homosexuality as a Jewish issue.” As Halper demonstrates, Langer was the first Jewish writer to articulate a homosexual identity using an internal Jewish vocabulary, and to see homosexuality as a concrete and continuous element of Jewish history and culture. Raised in a suburb of Prague in a secular Jewish family, he became attracted to Hasidism in his teen years, and at the age of 19 joined the Belzer Hasidim—an experience which he later describes as intensely homoerotic. During the First World War, Langer became involved in Zionist activism, and left the Hasidic world (although he remained an observant Jew) to study psychology and philosophy, becoming active in the Jewish literary scene of Prague (including a friendship with Franz Kafka). Around 1920, Langer began to think and write explicitly about Jewish homosexuality in both prose and poetry (see source 87). The title of his 1923 book, Die Erotik der Kabbala [The Erotic of Qabbala], is misleading—it is not restricted to Qabbala, but in fact attempts to trace the role of Eros, and in particular homoeroticism, in Jewish history from antiquity to the present (of the 1920s). Langer’s book was a response to contemporary antisemitic German theories of homosexuality, such as those of Hans Blüher, that portrayed the ‘manliness’ of male-male Eros as central to Western civilization and antithetical to Judaism. Instead, Langer argues that Eros was a central force in Judaism as well, drawing on a wide-ranging set of examples from Jewish history, including Rabbi Yoḥanan and Resh Laqish (see source 13), homoerotic medieval poetry (see sources 18-20 and 22-25), the male circles of sixteenth-century Qabbalists in Safed (see source 41), and the homoeroticism of the Hasidic yeshiva (see source 54), as in the excerpt presented here. The impulse to create a “gay canon” or comprehensive listing of “great homosexuals in history” was a common aspect of homosexual writing throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries; but Langer’s innovation was to incorporate it into a Jewish framework encompassing history, theology, sociology, and politics. Here he describes the circle of the yoshvim [yeshiva students] as an ideal all-male society, or Männerbund, held together by Eros (for a similar concept of Zionist pioneers as an erotic Männerbund, see source 76). When it came to the actual expression of homosexual desire, however, Langer could only say that the “official position” required those people to suppress their sexual energy for the benefit of society—a heroic tragedy that echoes other homosexual literature of the period (see source 64).

To understand what kind of love [Liebe] dwelled between the “yoshvim” [Talmudic scholars; literally: “those who sit”], one only has to step into the beis ha-midrash (“house of study”), where they are enveloped with their studies [wo sie sich mit ihrem Studium beschäftigen]. Here sit two young men (bachurim), with beards just beginning to cover their chins, “studying” assiduously over thick Talmud-folios. The one holds the other by his beard, looks deep into his eyes, and in this manner explains a complicated Talmud passage. And there, two friends (yedidim) pace around the hall deep in conversation, while embracing one another [sie halten einander umschlungen]. (During meals one can see that they always dine out of the same bowl). In the dark corner stand a pair. The younger of the two rests his back against the wall, the elder has the entire frontal part of his body literally pressed against him [der ältere liegt förmlich mit der ganzen Vorderseite seines Körpers an ihn gedrückt]; they look lovingly in each other’s eyes, but keep still. What could be playing out within their pure souls? They themselves don’t even know…

The boy’s soul, suddenly taken by an inexplicable yearning [Sehnsucht; alternatively: “lust”] for the rabbi, finds no peace at home. Not only in his nightly dreams, but also—and this is for the Hasidim a sign of grace [Gnade]—while awake the shining form of the rabbi appears before his eyes. Finally he decides: He leaves a comfortable home—often against his father’s will and his mother’s tears—and travels to the city of the rabbi, in order to “cleave” [anschmiegen; alternatively, “to nestle up to”] to him (to be dovek) forever. As soon as he arrives and it is determined that he is serious, he is greeted with open arms by the “Chevre” [social group]. Soon he finds himself in the middle of a circle of friends [Freundeskreis], who “draw near” [annähert] to him through various tenderness [Zärtlichkeiten] and it doesn’t take long to find an older student who has “the same soul” to study with, which he accepts with great joy. How blessed he feels.

115. A Gay Jewish Activist Advocates for Homosexual Solidarity (New York, 1965)

“Leo Ebreo” (Leo the Jew) was the pen name of Leo Joshua Skir (1932-2014), a gay Jewish activist and writer from New York. Skir was friends with noted Jewish Beat poets Allen Ginsberg and Elise Cowen (Cowen and Skir met in the 1940s on a Zionist training farm in Poughkeepsie), and is responsible for saving much of Cowen’s poetry after she committed suicide in 1962. While studying at Columbia, he spent the summer of 1951 on a kibbutz in Israel, but was disappointed to find that his burgeoning sense of his homosexual identity was not welcome in the kibbutz’s heteronormative environment. Skir returned to New York, and after graduating, continued to write for Jewish and non-Jewish literary journals while completing an MA at NYU; in 1975 he moved to Minneapolis, where he lived the rest of his life. Skir published many articles, theatre and film reviews, and a semi-autobiographical book titled Boychick: A Novel (1971). In this article, originally published in the lesbian magazine The Ladder in 1965, Skir draws on his background in the Zionist movement, and his experience as a first-generation American Jew, to call for solidarity among homosexuals, linking the fight for gay rights as part of the larger national and global struggle of oppressed minorities. He castigates his fellow homosexuals for holding themselves back in a self-declared “ghetto,” declaring that “when the Negro, the Jew, the homosexual, is known and a neighbor, he will cease to be a bogey,” and urging the readers to join him in fighting for full integration and equality. While religion was a popular topic in gay and lesbian magazines in the 1950s and 1960s, it was almost always Christianity being discussed, and usually with negative implications. Skir’s explicit and thoughtful engagement with Judaism is a unique and unprecedented window into the relationship of gay Jewish activists with the American Jewish community of the 1950s and 1960s.

A Homosexual Ghetto? by LEO EBREO

When I was younger—about sixteen—I was an active Zionist. I believed that the best thing for American Jews, in fact all Jews, to do would be to go to Israel and live in a kibbutz (collective). I belonged to a Zionist “movement” and tried to get the Jews I knew to join. I expected of course that few would want to emigrate, but I thought that most would be interested in helping Israel and the Zionist movement.

This was not the case. I was met, very often, by an extraordinary hostility. It was not until years later, reading works on Jewish self-hatred, Negro self-hatred, that I could realize that I had frightened some already-frightened people.

For this fright I have still no cure. The rational arguments which I gave my Jewish friends then, I would give them now.

These arguments (both the ones they gave me and my replies) came back to me recently when I began working in the homophile movement and speaking to homosexual friends about it. When I attempted to draw some parallel between the Jew’s struggle for his rights and the homosexual’s struggle for his, I was often stopped short with the explanation that there could be no parallel because one was a “religious problem” and the other a “sexual problem.” I tried, without success, to show how much the Negro’s struggle paralleled that of the Jew, even though the Negro “problem” was a “race problem” and not a “religious problem.”

As I have said, I have no rational arguments against the surrender to fear, and the rejection of self that lies behind it. This essay is not written for those who have surrendered to fear, but for the others, the fighters.

I think we need to constantly reaffirm our perspective in the fight for homophile rights, to realize that we are part of a broad, general movement towards a better, freer, happier world.

This struggle of ours for complete acceptance will probably continue throughout our lifetime, as will the struggle of the Negro and the Jew. Oceans of hatred, unreason, rejection, craven fear will continue to come from the “other” world (of the white, the gentile, the heterosexual), will continue to infect many individuals within these oppressed minorities.

And in this light, I think my parallel Zionist experience will show us both the currents of the Opposition from within our own ranks, and the answers which we must make. The objections my Jewish friends raised were as follows;

(1) “I’m not that Jewish.” “Being Jewish isn’t that important to me.” (2) “I don’t want to go to Israel.” (3) “You are making the situation bad for us. There isn’t any great problem. Discretion is the password. You are being offensive. You are putting us in a GHETTO, or would If we allowed you.”

The answers I gave then come back to me now:

1. “I’m not that Jewish.” What does “that” mean? Orthodoxy? Many Zionists are not that orthodox. To be Jewish does not mean a series of outward observances. It means being part of a people, recognizing their history, trying to find within that historical experience your lesson, your place.

2. “I don’t want to go to Israel.” Perhaps not. Perhaps not now when conditions for Jewish life are good in the United States (as they were once in Germany). But don’t you want Israel to exist? Some place which will represent the Jews, to which they can go if oppressed? What other nation would try Eichmann? And if an Israel had existed in the time of Nazi Germany, could not the Jews have gone there? And, with an Israel to represent them, might there not have been some action taken to prevent the extermination of the Jews in Europe?

3. “You are making the situation bad for us… You are putting us in a ghetto.” Nonsense. Israel is not a ghetto. It is a place where the Jew is, if anything, more normal than in other countries, a place where he is a farmer, seaman, shepherd, rather than furrier and candy store owner.

Of course, the Jews who offered me these arguments were not convinced by my replies. They had a certain picture in their minds of what being “Jewish” was—a curious, narrow, ill-informed vision defined by an old man (always old) with a long white beard and a yamulka and a long black coat, a Yiddish accent, the boredom of prayer mumbled and half-heard on certain holy days in a synagogue. The reality of Jewish existence, history, aspirations was unknown to them. Small wonder then that they could not imagine the reality of Israel. Its youth, vitality, the variety of its peoples.

So they hung back—often, too often, proud of not being “too Jewish,” changing their names to less Jewish-sounding ones, the girls having their noses shortened surgically.

And yet, as the years passed, I saw them grow more confident, less apologetic of their Judaism, because, in spite of themselves, they were proud of Israel, that nation whose growth they had at first resented.

And so. I think, it will be with those homosexual friends of mine who are now fearful, even resentful, of the homophile organizations. Their reactions now parallel, almost word for word, those of the Jews:

1. “I’m not that homosexual.” Here too, the image the outside world pictures is used by those raising this objection. One doesn’t have to fit the stereotype to be that homosexual. (Yet to a certain extent we must work with the outside world’s definition of the homosexual.) The German Jews were the most assimilated, often not knowing Yiddish, often not religious, often converted to Christianity. Still they were exterminated. Similarly, too often the one who suffers from persecution of homosexuals is the respectable married man, like [Walter Wilson] Jenkins, who makes a single slip. No one trying to defend Jenkins (and there were few who did, to our eternal shame) noted that he wasn’t that homosexual.

2. “I don’t want to be a member of a homophile organization.” My full sympathies. Neither do I. But I do belong. Just as I belong to the UJA, to the NAACP. Being in the Zionist movement, like being in the homophile movement, was to some extent a burden to me. It is a trial to pay dues, to attend meetings, to hear lectures, and—most of all—to have to deal with so many people and with their many, many faults. (St. Theresa, the Jewess of Avila, said that people were a great trial to her. That was the 16th century, and people are still a great trial.) But don’t you want the homophile movement to exist? Don’t you want to see some organization represent homosexuals, stand up for their rights?

Fighting though I was for the state of Israel, I was still—and am still—a confirmed internationalist. But to arrive at that place in history, these intermediate steps are necessary. It is not a certain good—an absolute good—that there be a state of Israel, with borders, army, taxes, ministries. But until there are no French, German, Russian, American nationalities, I think it unwise to eliminate the Jewish nationality, which all these nations have at times acknowledged (before its official creation) by discriminating against it.

The question you must ask yourself is not whether you “like” to join or at least support a homophile organization (or a civil rights organization), but whether it is needed. And the homophile movement is needed, as Israel is needed, at this point in history.

3. “Your homophile organizations make our situation worse… Discretion is the password. You are being offensive. You are putting homosexuals in a ghetto.” Here again we are dealing often with homosexual fear and self-hatred and self-rejection.

This very word—GHETTO—has been used to me by homosexuals outside the movement. The homosexual who says this has accepted the negative picture of the homosexual drawn by the outside world. And, just as the American Jew may imagine a nation of candy store keepers with Yiddish accents and skullcaps, so the “assimilated” homosexual, from his troglodyte perspective, may imagine an assembly of campy ballet dancers and hair dressers.

There is already something of a ghetto pattern for homosexuals, because of the pressures put on them to confine themselves to certain vocations where they are “expected” and to isolate themselves. But the aim of the homophile organizations, like that of the NAACP, the UJA, Is not for further ghettoization but for integration, for equality.

However, there is a radical difference between the situation of the homosexual and that of the Negro and Jew in relation to their organizations. The Negro can rarely “pass.” The Jew might be able to, but he is under many pressures, especially family upbringing and sometimes family presence, not to. The homosexual, on the other hand, can usually “pass” easily and does not have the family pressure as an inducement to declare himself. If anything, there is another pressure, to pass for the sake of family appearances.

Thus the individual homosexual may claim that membership in a homophile organization, rather than enabling him to normalize his situation, might endanger the assimilation, the equality he can achieve with just a bit of “discretion” and silence. This argument has a certain cogency. Its limitation is that it is a solution for the individual homosexual.

It is the “solution” (or, to be charitable, the “path”) taken by the average homosexual, especially the one outside a city, or who is not in touch with the gay community. And this is not a solution, a path, which is to be avoided. For certain people, in positions in the government, in schools, there may be no choice but secrecy at this time.

But the price can be a terrible one. It is, as I have said, an individual solution. Often, too often, it results in an isolation for the individual, sometimes a world of pathetic furtive sexuality or public lavatory sex—shameful, inadequate ridiculous, dangerous. Even when the hidden homosexual has a mate, the union still has a peculiar isolate character, being secret, disguised. Thus the homosexual who passes is often in a ghetto composed of one person, sometimes of two. An individual solution perhaps, but hardly a permanent one, or a good one.

Those of us who are active in the homophile movement feel ourselves working for those outside and fearful of joining. We are working for a day when our organizations will be strong enough, active enough, to protect the rights of those in public employment (such as teachers), in the armed services, in government. The homosexual who is accepted as a homosexual will be a fuller, better person than the furtive imitation-heterosexual who has found his individual “solution.”

The aim of the homophile organizations is not to draw a small circle and place the homosexual within it. The very term “homosexual” (only 68 years old if we are to believe the Oxford English Dictionary) may not be used with such frequency in the Larger Society which we are working to create. We are drawing a circle—but a LARGE circle, to draw the large society of which we are a part, in. We are asking to be accepted. This acceptance which the homosexual minority needs, wants, can only be gotten when it is asked for—if need be, DEMONSTRATED for through groups like ECHO and their picket lines.

The drive to eliminate discrimination against homosexuals (sex fascism) is a direct parallel to the drive to eliminate discrimination against Negroes (race fascism). These minority movements are not attempts to overthrow the white race, or to destroy the institution of the family, but to allow a fuller growth of human potential, breaking down the barriers against a strange race or sexuality. When the Negro, the Jew, the homosexual, is known and a neighbor, he will cease to be a bogey.

We are working towards that world in which there will be respect for, enjoyment of, the differences in nationality, race, sexuality, when the homosexual impulse is seen as part of the continuum of love which leads some persons to be husbands and wives, others to be parents, others to be lovers of their fellow men and women, and still others to be celibate and devote themselves to humanity or deity.

In that world there will also be greater variety. Our stratified ideas of masculinity and femininity will long have been altered. (Have you noticed that men’s greeting cards have either a gun and mallard ducks, or a fishing rod and trout?)

It is this world, where the barriers of nation, sex, race have been broken, this larger, non-ghettoized world, that minority groups are organizing to work toward. And it is this picture of the larger world of the future that we must hold up when we are accused, by the very existence of homophile organizations at this point in history, of wanting to ghettoize homosexuals.

“Knock, and it shall be opened unto you.”